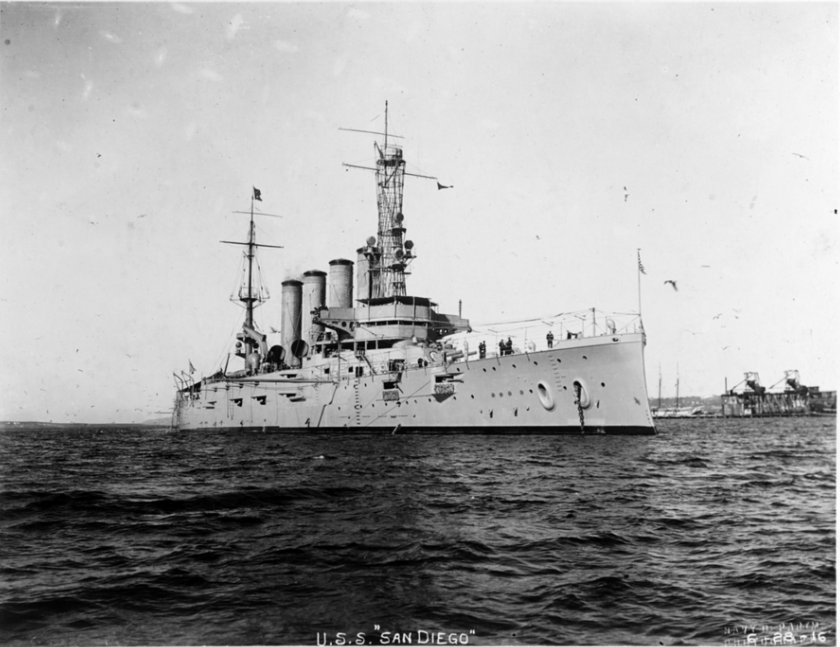

Mine or torpedo? For a hundred years, the cause of the explosion that sank USS San Diego (ACR-6) has been a mystery. But now researchers are on an expedition to determine what exactly caused a Navy armored cruiser to sink 100 years ago within eyesight of New York City as the U.S. was entering World War I.

On July 19, 1918, San Diego was returning to New York from Portsmouth N.H., in preparation to escort a convey to Europe. At about 11:05 a.m., while steaming just south of Long Island, an explosion ripped open the midship section, causing the ship to quickly list 17 degrees, flooding the hull and ultimately sinking 28 minutes later, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC).

“For the six guys who lost their lives on San Diego, they were nearing New York City, it was 11 o’clock in the morning, they were probably thinking about liberty and it all changed in an instant,” Paul Taylor, a NHHC spokesman told USNI News.

Now, on the hundredth anniversary of San Diego’s sinking, the Navy held a wreath laying ceremony at the surface above where the ship sank and sent a special dive team down to the sea floor to try determining exactly what caused the sinking.

For much of the past century, Navy officials, historians and scuba divers visiting the wreck thought a torpedo caused the explosion, but recent surveys of the wreck, using high-tech scanning and sonar equipment, suggest the blast may have been caused by a sea mine instead, Taylor said.

A German submarine, U-156, is believed responsible for sinking San Diego – the only major U.S. Navy ship lost in the first world war, according to the NHHC. U-156 was sent to lay a string of mines outside of New York Harbor, but details of the submarine’s activities are not known because U-156 never returned to port, according to the NHHC.

A survey of the site last September provided good sonar data, but the visual data was not conclusive to determine whether a mine or torpedo caused the sinking, Taylor said. Researchers wanted another try at surveying the site when weather conditions would be considered favorable for a survey.

The anniversary of San Diego’s sinking happens to align with a time when the Navy’s Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit Two was due for a training exercise and the Military Sealift Command rescue and salvage ship USNS Grasp (T- ARS-51) was available, Taylor said. Divers from the Salvage Unit Two are visiting the wreck to provide visual details of the site that were not available during recent surveys.

What sets San Diego apart from other shipwrecks is the ship’s location is relatively easy to access — it’s been a favorite spot for recreational scuba divers for years – and it offers researchers a rare peek at what happens to a hull after being sunk by a mine, Taylor said.

“It’s unusual to have such good access to a ship that was sunk [like that],” Taylor said.

The location also provides a challenge for the NHHC, Taylor added. Over the years, contrary to federal law, divers have scoured the wreck for souvenirs. Both propellers have been removed but lost at sea, and at least six recreational divers have died trying to illegally recover artifacts from the wreck, according to the NHHC.

“The wreck appears to be in pretty good condition,” Taylor said. “It’s is starting to show some deterioration midsection where the explosion occurred, and the hull is starting to cave in.”

The wreck is still Navy property, and the site is considered the final resting place for six sailors who died – their final resting place marked by the turtled hull on the sea floor about 100 feet below the sea surface, southeast of Fire Island N.Y.

The Navy can potentially use information about how the ship sank and its condition a century later in ship design, Taylor said. Usually, ships sunk by mines are not easily accessible, because of their location in deep waters or far from shore. Or, as happens frequently, after a conflict, the local authorities concentrated on removing shipwrecks consider navigation hazards without considering any lessons to be learned from how the ships sank, Taylor said.

Aside from the lessons learned, Taylor said it’s important for the Navy to keep an eye on these sites, which are considered hallowed ground just as is the case with military cemeteries. For sailors today, visiting sites of wrecks sends a powerful message, Taylor said.

“It’s important for them to know their service and their sacrifice will be remembered,” Taylor said.