This post has been updated to include a statement from Rolls-Royce, and again to include a statement from Naval Sea Systems Command.

Zumwalt-class destroyer Michael Monsoor (DDG-1001) will need to have a main turbine engine replaced before the ship can sail to San Diego for its combat system activation, after suffering damage to the turbine blades during acceptance trials, the Program Executive Officer for Ships told USNI News.

Rear Adm. William Galinis said today that Monsoor remained in Bath, Maine, for a post-delivery availability and that, “regrettably, coming off her acceptance trials we found a problem with one of the main turbine engines that drives one of the main generators; we’re having to change it out. So we’re working very closely with Bath Iron Works, with Rolls-Royce to get that engine changed out before she leaves Bath later this fall and sails to San Diego to start her combat system activation availability next year.”

After his remarks at a Navy League breakfast event, Galinis told USNI News that the MT30 marine gas turbine showed no signs of malfunctioning during the sea trials, but the damage was found in a post-trials inspection.

“The problem we had coming off of acceptance trials was actually the turbine blades – so think of a jet engine on the side of an airplane, the blades that you see – we actually had some dings, some damage to those turbine blades,” he said.

“We found that after the sea trial through what we call a borescope inspection, where we actually put a visual and optical device inside the turbine to kind of look at this. And we determined that it was best to change that turbine out before we actually transited the ship to San Diego.”

Monsoor completed acceptance trials in February, and the Navy accepted partial delivery of the ship in April. According to Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), the damage was discovered in February during a post-cleaning inspection of the engine.

Galinis said part of the reason it has taken so long to replace the engine is that, with the MT30 being so large, a special rail system is needed to remove the engine and put in a new one. That system hadn’t yet been designed when the Navy realized it needed one, so engineers had to finish the design and then install the system.

“So that’s what’s taken us a little bit,” the rear admiral said.

Galinis said the Navy has already checked USS Zumwalt (DDG-1000) and found no damage to its main turbine engine.

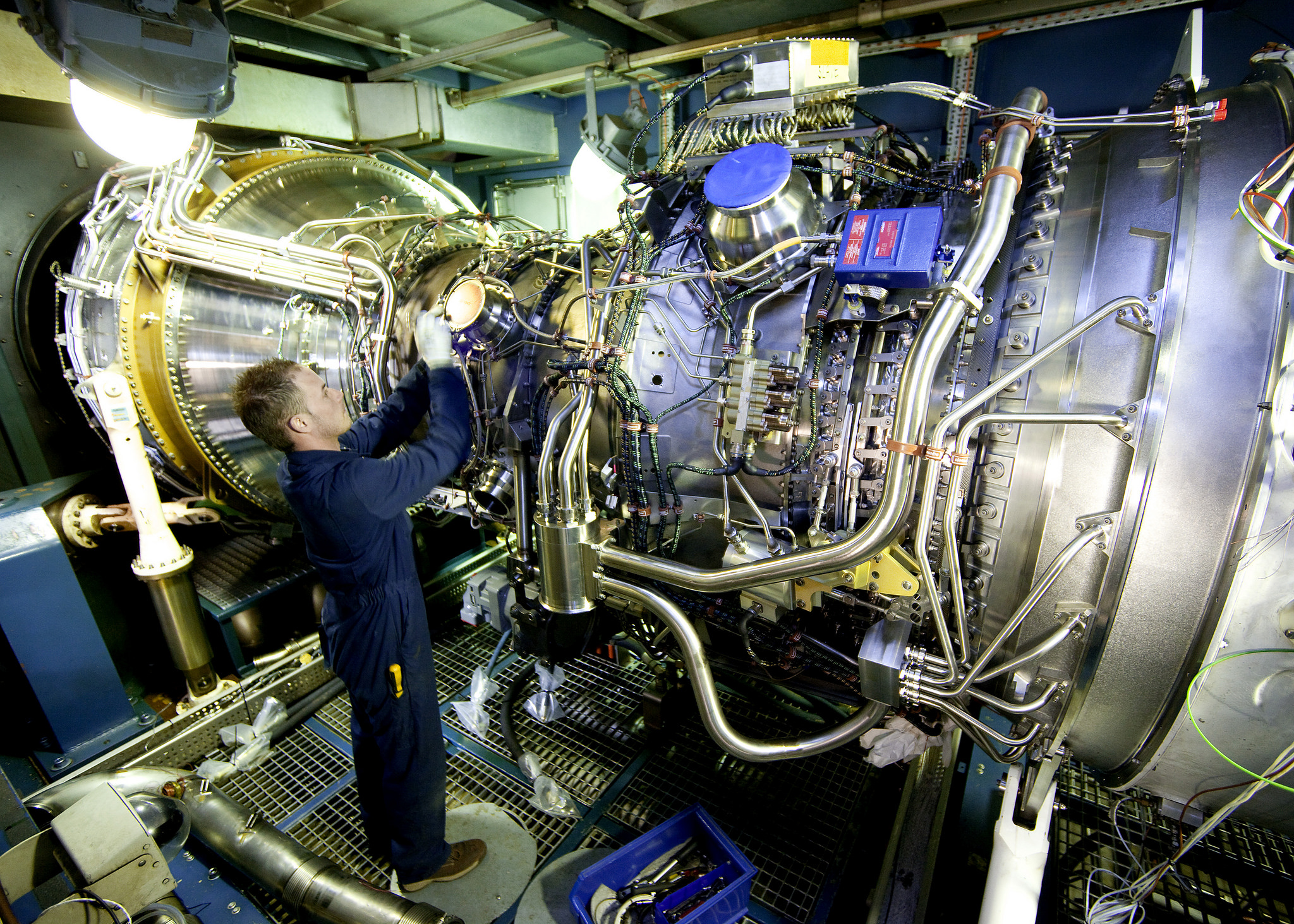

In the U.S., the $20-million Rolls-Royce MT30 is installed on not only the Zumwalt-class but also on the Navy’s Freedom-variant of Littoral Combat Ships. Internationally, the gas turbine –derived from Rolls’ Trent 800 aviation engine – is in use on the U.K. Royal Navy’s Queen Elizabeth-class carriers, the under-construction Royal Navy Type 26 frigate, the planned Daegu-class frigate for South Korea and the Italian Navy’s new Trieste amphibious warship.

The engine, introduced in 2001, can generate up to 40 megawatts of power and is the key to the Zumwalt-class’s Integrated Power System. The MT30s drive the destroyer’s massive electrical grid that drives everything from the ship’s sensors to a massive electric motor that drives the ship’s shafts.

“We’re working closely with the U.S. Navy and the team at Bath Iron Works to swap one of the two MT30 gas turbines on Michael Monsoor,” a spokesperson for Rolls-Royce told USNI News in a Tuesday statement. “Preparations are underway to swap the engine as quickly as possible to minimize downtime for the ship.”

Due to the unexpected damage to the blades, which have not been found elsewhere in the fleet, Galinis declined to speculate as to what or who was to blame for the issue.

“Until we get the engine out and actually get a chance to do a root-cause analysis, we really don’t know what caused the damage. What I will tell you is we ran the ship at full power and there was no indication of a problem while the ship was underway. We have vibration sensors on the engine to monitor for this type of thing, so even though the damage was there, it wasn’t to the level where we even saw anything on trials. And even, we had additional instrumentation on the engine during trials when we take a ship to sea for testing, and we didn’t see anything,” he said.

For now, because the engines are government-furnished equipment, the Navy will have to pay for the removal of the engine and the installation of the new one. If the problem turns out to be a Rolls-Royce manufacturing or quality assurance issue, the Navy could look to recoup that money from them.

According to NAVSEA spokesman Alan Baribeau, “removal and replacement of the engine is concurrently taking place with the ship’s planned Industrial Post-Delivery Availability at Bath Iron Works shipyard in Bath, Maine. Despite the engine removal, Michael Monsoor is still expected to arrive in her San Diego homeport on schedule by December 2018.”

Michael Monsoor suffered another setback in December 2017, when a problem with the electrical system caused the destroyer to come back to Bath a day after leaving for sea trials. A harmonic filter, which prevents unintended power fluctuations from damaging sensitive equipment in complex electrical systems, failed. The ship was able to resume its sea trials after the electrical system was repaired.

Zumwalt suffered its share of engineering challenges as well, with several propulsion system failures during its transit from Maine to San Diego. The current MT30 problem, though, is unrelated to any other casualty the ship class has suffered to date.

As for the rest of the ship class, Galinis said in his talk that Zumwalt is nearing the end of its combat system activation availability. The destroyer is conducting its lightoff assessment this week and doing well so far, and was preparing to go back to sea by the end of August.

The third and final ship in the class, the future Lyndon B. Johnson (DDG-1002) remains on track at Bath and is set to launch by the end of the year, with sea trials occurring in 2019.

Sam LaGrone contributed to this report.