The Marine Corps is investing in a suite of virtual and constructive training systems, augmented reality goggles and other emerging technologies to give Marines more repetitions and, in some cases, more authentic experiences during training than the service could provide before.

Among the top priorities as the Marines invest in more technologies, though, is ensuring they can be networked together to allow for cross-community training events – fire support teams talking to artillery units, forward air controllers talking to pilots, ground combat units talking to the logistics teams that support them, and so on.

The Marine Corps had in 2015 planned to conduct an analysis of alternatives for a Live, Virtual, and Constructive Training Environment (LVC-TE) architecture that would network the simulators together, but due to continuing resolutions and other factors the AoA just began last year, Lt. Col. Byron Harder, the branch head for the Marine Corps Synthetic Training Environment and the LVC-TE capabilities integration officer, told USNI News during a May 8 interview. The AoA is about halfway done and should wrap up around October, he said.

The AoA looks at several back-end options for netting together the technologies that the Marine Corps and the Office of Naval Research (ONR) have been pursuing – including using the joint force’s network or creating a new one. The process defines the training requirements, based around a variety of scenarios at the company and battalion levels up to a Marine Expeditionary Force level, and then defines training effectiveness, cost and risk for each of the LVC-TE backbone options.

“We’ve kind of realized we just can’t train those pockets of Marines. … You really need to be able to connect those different training audiences to work their procedures and do those supporting and supported relationships and do those standardized procedures and get used to working with people, Marines in other communities – as you send your calls for fires, requests for support, and do battle handoffs with them and work all those different things. So that necessitates an integration between a bunch of different training systems that were originally not designed or procured to ever work with each other,” Harder said.

The lieutenant colonel, who has a doctorate of philosophy in modeling, virtual environments and simulation, said other benefits of LVC training are the ability to simulate large formations instead of trying to amass that many people in one place for a live exercise; the ability to practice high-end or sensitive tactics “behind the curtain” where an adversary can’t spy on them; the ability to do things the military couldn’t do in real life outside of a warzone, such as use a jammer on a civilian area; and the ability to practice certain tactics without risking friendly-fire casualties, such as suppressing an enemy with fires and then stopping as soon as friendly forces reach that location.

“We’ll never get away from live training because the natural realism of being out in the real world will never be completely replaced by simulations, because any simulation is something short of reality. So that will always be, at minimum, our graduation exercise. But we found that through the multiple repetitions you can get in simulations and the fact that you can focus those simulations on particular areas that might be your problem points – we look at simulation as a gateway to live,” Harder said.

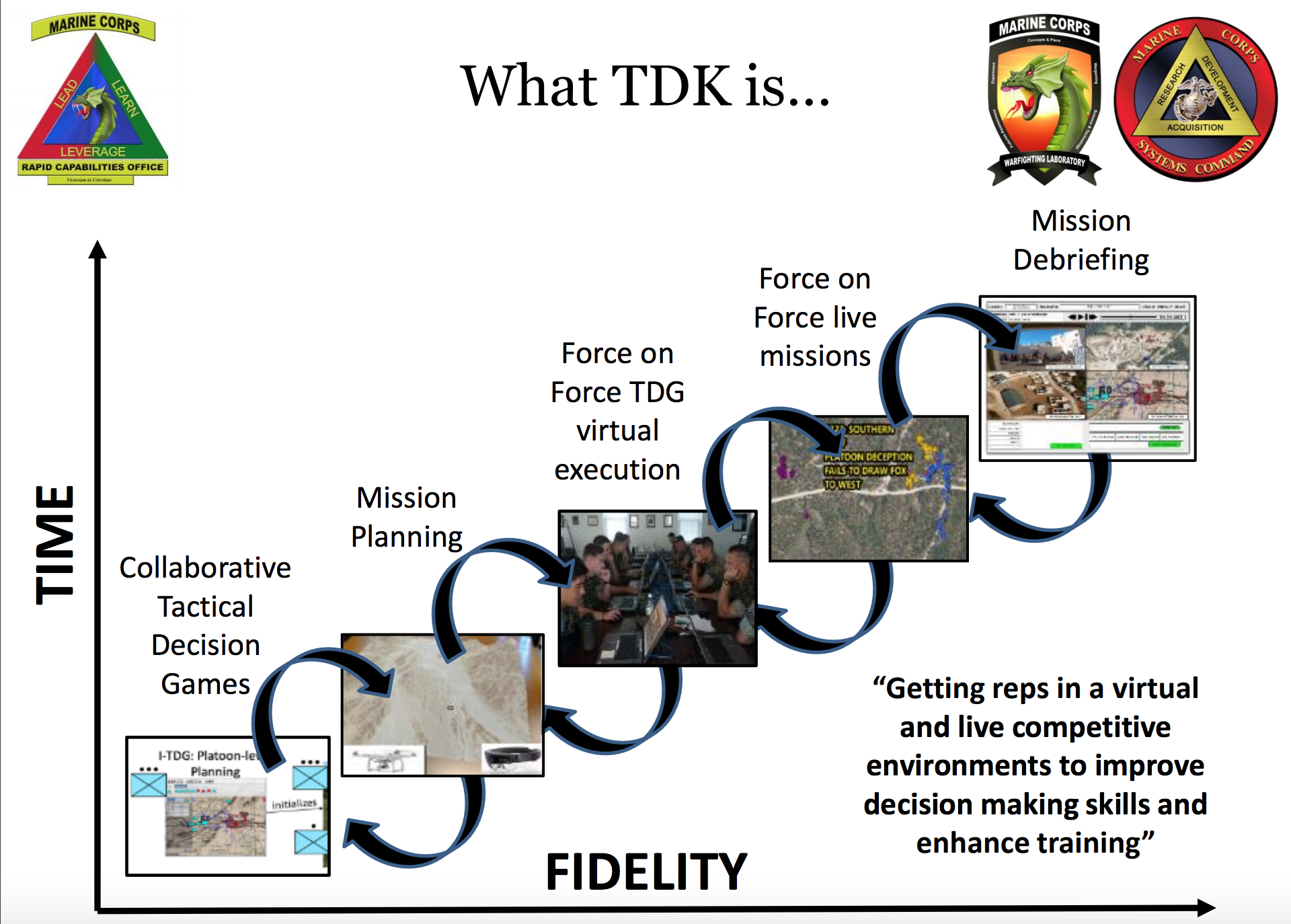

One package of LVC systems the Marines are now working with is the Tactical Decision Kit, which grew out of an ONR effort and was adopted by the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines, who wanted to bring more simulation into their training events.

Harder said the kit includes a range of virtual and constructive training systems, as well as supporting systems like drones and GPS trackers that enhances the whole continuum of training.

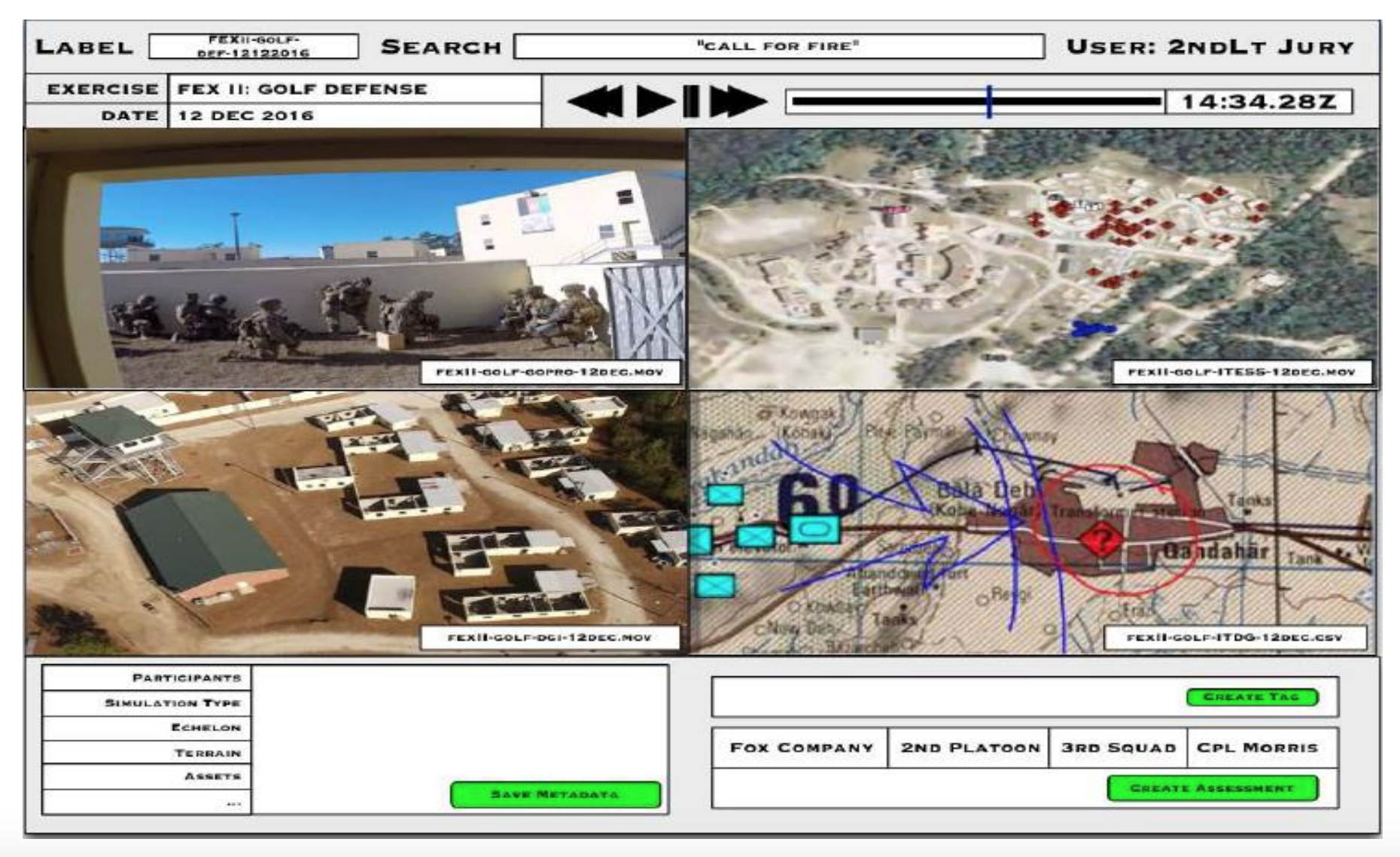

The suite begins with an Interactive Tactical Decision Game, where a small unit leader could be presented with a situation, see the available resources, and start to map out a plan. The Augmented Reality (AR) Sandtable, which uses the Microsoft Hololens, then allows the small unit leader and up to three teammates to view three-dimensional terrain with AR goggles and begin to think through the positions of machine guns, for example. In the Virtual Battlespace, which is like a first-person shooter video game, each Marine is represented by an avatar, and the Marines can run through scenarios with as many repetitions as they want. Once the units are ready to move into live training, a force-on-force training system puts a GPS tracker on each Marine and a laser system on their weapons to track who was where during the training scenario, who hit their target, who was shot and more. That data, supplemented with time-stamped data from drones, Go-Pros and other sources, is imported into the Smart After-Action Review Tool to allow for a thorough post-mortem that individuals and units can learn from.

Harder said it is clear from the Tactical Decision Kits that simulation can be applied as training increases in unit size, in the complexity of the scenario and in fidelity – from tabletop games to real training in the field. A couple key technology areas the military and the gaming industry are pursuing are set to make that continuum of training even better.

First, Harder said the Marine Corps is very interested in augmented reality goggles, especially if they can be reduced to the weight and size of the ballistic goggles the Marines already wear. Whereas some trainer systems exist in a dome room, where users would see a terrain around them and be able to carry out their mission, moving that training outside with AR goggles would provide an even better experience.

The Mobile Fire Support Trainer for fire support teams, for example: “without having to deploy artillery units out to the field or have tank hulls to shoot at, they can put on those goggles and they can send a call for fire. It will insert targets, potentially even moving targets – which we typically don’t get, we’re usually just shooting at old rusty tank hulls that are sitting on the ground. So we can have moving targets. We can integrate those fires with simulated friendly forces that are moving towards an objective – so you can validate that you can turn off your fires at the right time so that you don’t cause friendly casualties – all sorts of interesting things that you can do with this MFTS technology,” Harder said.

Though the MFST uses goggles that are heavier than the Marines’ ballistic goggles, and therefore not quite the technology the service would want to invest in for all Marines’ training, Harder said the fire support teams tend to operate from a stationary position and therefore the technology is good enough to invest in for this one community.

“It’s a nice first step towards providing augmented reality training capability out there, and it’s one of the unique projects that the Marine Corps has that, as far as I know, no other services have,” he said, adding that, though the program is still in the engineering and manufacturing development phase and trying to reduce the weight a bit more, a fielding plan is already in place to bring MFST to schoolhouses first and then to operational units.

MFST, which transitioned from ONR to the Marine Corps in 2016, has eight low-rate initial production units that will be ready for testing this summer. Initial operational capability with 235 units is planned for 2020, and full operational capability with 696 units is planned for 2023, Marine Corps Training and Education Command spokesman Capt. Joshua Pena told USNI News.

A second tech development area the Marines are keeping a close eye on is what the gaming industry is doing to enhance cognitive behavior representation – or ensuring that all the people, animals and items in the background of the scenario make realistic decisions. As commanders have more tools in the field for situational awareness, that has to be reflected in simulators now too, which means the simulator must be more detailed to reflect this new way commanders can see the battlefield around them.

“Back just 10 or 20 years ago when we were just moving large formations across the battlefield, one icon could maybe represent 100 Marines. But now we’ve got unmanned platforms with video capability on them that could be anywhere on the battlefield, so at any moment the commander wants to be able to say, show me a live video feed of that spot right there; so now you have to be able to simulate not just, here’s an icon representing 100 people, you have to be able to zoom in and see what are those people doing and are they acting realistically, and you’re going to want to be making decisions in real-time based on what you see,” Harder explained.

“So that’s a much higher level of human behavior representation that we need to be able to provide. Both the sort of functional capability of do those individual entities make the right decisions within their communities or their units, but also just the distributed processing capability to run all those many decision-making engines without having the whole computer system come crashing down.”

Harder said he’s not expected the Marines to have a full, integrated Live, Virtual and Constructive training environment set up until at least 2025 – though the Marine Corps Operating Concept highlights the importance of training, and LVC training in particular, that doesn’t always translate to sufficient funding. But, he said, several communities in the Marine Corps are taking it upon themselves to create integrated LVC training experiences, and their hunger for the capability and success in proving its benefits helps him argue for more service support for the technologies and their integration.

At Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center 29 Palms in California, Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron-One (MAWTS-1), the Marine Air Ground Task Force (MAGTF) Training Command and I Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) decided to pool resources and create a temporary integrated training event, Harder said. In North Carolina, II MEF’s Battle Simulation Center will sometimes connect with flight simulators at nearby Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point.

“If it wasn’t important, they wouldn’t be doing it. The challenge is, though, that there is not an institutional Marine Corps program to support those types of events. So that’s the shortfall that I’m trying to close with establishing that LVC-TE program, because we want to provide a funded, well-designed standing capability that a unit can easily tap into whenever they want to conduct that type of training,” Harder said.