Recent challenges to Navy recruiting and retention have left the sea service 11,000 sailors short of its required manpower level in the short term, and about 50,000 sailors short of the estimated force needed to crew a 355-ship fleet.

Though the Navy has successfully fought for additional manpower funding in the last few years, the service is near its lowest end strength in almost a decade. As of Friday, the Navy had 323,947 active duty sailors, which includes 319,421 working sailors and the midshipmen brigade at the U.S. Naval Academy.

Navy officials recognize the challenges they’re facing when recruiting and retaining sailors. Service leaders have long hinted at the competition for talent in public speeches and congressional testimony and have waged a campaign to retain sailors. But lawmakers worry the service does not have a long-term manpower ramp-up plan to accompany the shipbuilding ramp-up, and it is also unclear how the Navy will bring in 11,000 new personnel in the next year and a half.

“We are in a growing Navy. This requires more people, at a time when we are still working our way back to desired sea duty manning levels, and when the competition for talent is especially keen. We will certainly recruit and train many more sailors to help meet these demands, but that will not be enough,” Vice Adm. Robert Burke, the chief of Naval Personnel, said in a December instruction canceling the early outs programs, which had allowed sailors to leave active duty before their commitments were complete.

On Wednesday, Burke is scheduled to appear before the House Armed Services military personnel subcommittee, where it is likely he’ll be asked by lawmakers about the Navy’s recruiting and retention plans.

However, the Navy currently does not have a long-term force structure strategy. A force structure plan is being created, a Navy spokesperson told USNI News earlier this month, but the Navy would not comment on future personnel needs because force structure plan is still under development.

Some lawmakers are skeptical there is a plan being developed, and if one is created, how well it will address growing manning needs.

“Given the fact that this administration just submitted a 30-year shipbuilding plan that would never actually achieve 355 ships, it seems pretty clear to me that they don’t have a realistic plan to man a 355-ship Navy, nor a realistic plan to build a 355-ship Navy at this point,” Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), the House Armed Services Committee ranking member, told USNI News in a written statement.

Defining the Shortfall

The Navy has 18 months to add the nearly 11,400 new sailors needed to hit its publicly stated projected end-strength goal for Fiscal Year 2019 – the largest proposed increase in active duty personnel in more than a generation.

Within the next five years, the Navy projects growing the number of all active duty sailors by about 20,700 to nearly 344,800, a 6.4 percent jump from the 323,947 sailors now on active duty, according to its FY 2019 budget request.

Currently, about one of every three sailors – about 111,600 sailors, including those in carrier air wings – serve aboard ships, according to a USNI News calculation of how many sailors currently serve on each type of ship, based on Navy data.

The Navy is already on a growth path based on an aggressive ship construction program over the last several years that saw the largest increase in shipbuilding in a generation. As the new hulls come online during the next several years the Navy will already need to increase the sea-going force by about 7,700 sailors to man the ships currently under contract.

At a time when the Navy’s size has remained relatively flat – at close to 320,000 sailors for the past five years – such a jump in the number of sailors as proposed by the Navy’s FY 2019 budget request could appear optimistic.

The need for increased manning becomes more pronounced during the next couple of decades as the Navy plans to increase the fleet to 355-ships.

Estimating the total number of sailors the Navy needs for its fleet in the 2050s is difficult, as it is unclear how many sailors will be required to operate new classes of ships; during that time, today’s Arleigh Burke-class destroyers and Littoral Combat Ships may be replaced by a Future Surface Combatant family of ships that’s yet to be designed, for example. Increased automation and a reliance on unmanned systems operating off ships could help reduce the needs for sailors on future classes of ships.

Taking all of these factors into account, a recent study released by the Congressional Budget Office predicts the Navy would need about 125,000 ship-based sailors by 2047 to crew a 355-ship fleet.

Overall, if the Navy’s ratio of about one out of every three sailors serving aboard a ship were to hold through the fleet expanding to 355 ships, the Navy would need close to 375,000 total active duty sailors, a 17-percent increase from today’s end strength.

The last time the Navy had 376,000 sailors was 2003 – just before the service instituted its optimal manning program and shed active duty sailors year after year for the next decade, finally settling in 2013 at what has basically been the size of the Navy for the past five years: about 320,000 active duty sailors.

Mitigating the Shortfall

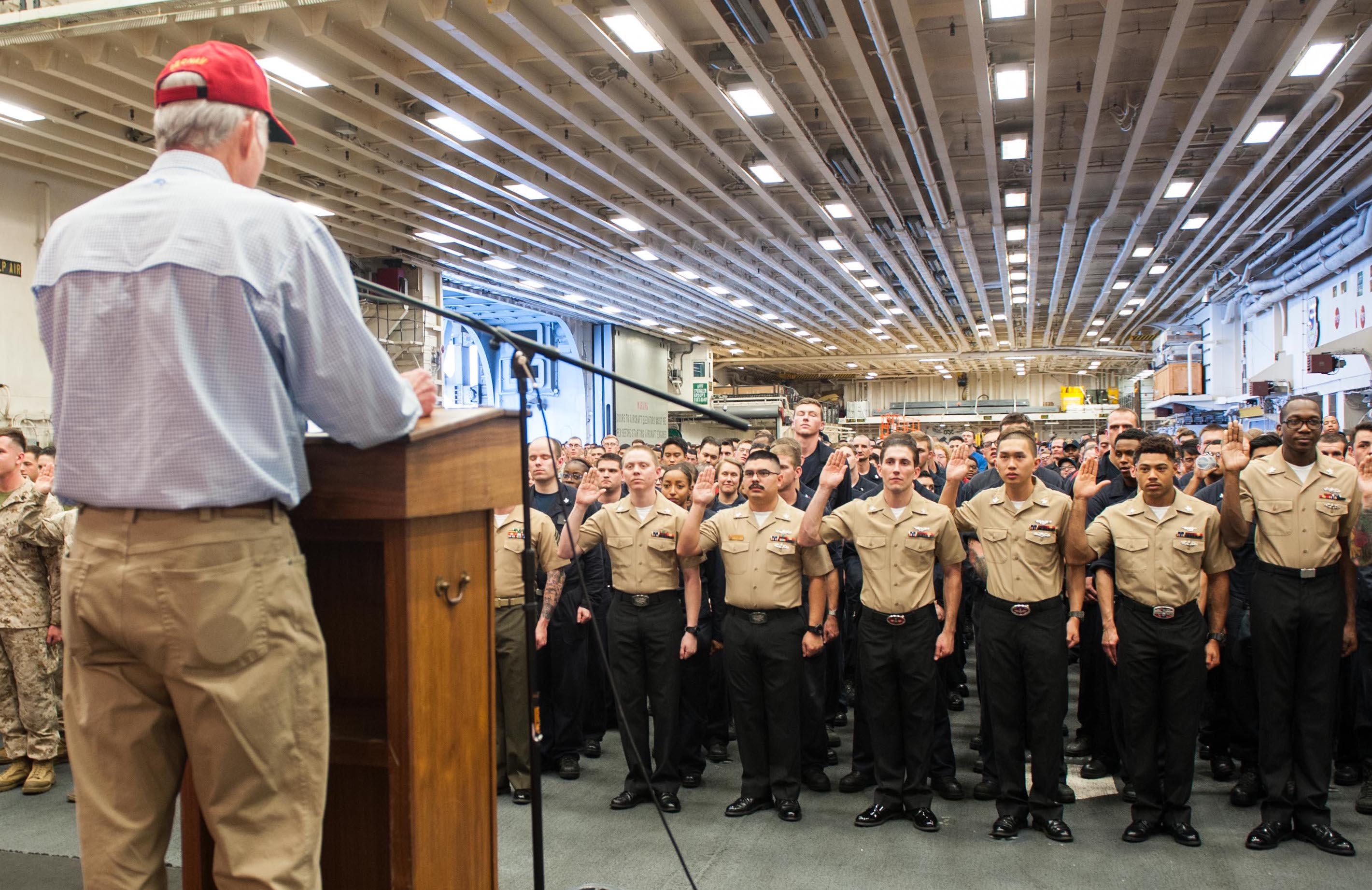

People are the Navy’s greatest asset, Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spencer said in December at the Naval Institute Defense Forum Washington.

“We don’t win without them, and we need to keep the winners that we have,” Spencer said.

“Our ships, planes, submarines, vehicles – they’re all just hunks of metal. They can’t do much without the human interface.”

Navy officials are not shy about the need to recruit and retain sailors. A series of initiatives are geared toward attracting new sailors and keeping current sailors in uniform. The Navy’s 2019 budget request for personnel, according to a Navy spokesperson, is meant to “reduce manning gaps at sea, reflect force structure decisions, and improve Fleet readiness.”

Part of the Navy’s strategy is continuing to promote serving in the Navy as a way to experience adventure, acquire training and pay for advanced education, Capt. Vincent Segars, the Navy’s director of military community management in Millington, Tenn., recently told USNI News.

The Navy met its 2017 recruiting and retention targets – 45,546 total active duty and reserve officers and enlisted joined in FY 2017. But Segars said the service is competing for talent against a private sector often offering more lucrative pay, better hours, and better quality of life. Traditional selling points are not going to be enough to retain talent, he said, especially during today’s tight labor market.

“We are competing for talent, and we have to mature our policies to deal with that,” he said.

Sailor 2025, the Navy’s program to create policies making serving in the Navy easier for today’s sailors, is part of the strategy Segars said will help recruit and retain talent.

The program includes several initiatives, such as revamping the pay system, overhauling training to include more waterfront training in the Ready, Relevant Learning initiative, and allowing sailors the option to take short breaks from their Navy service to start a family or work in the private sector.

Navy leadership also believes the military’s new retirement system, which started in January, offers a new way to compete with the private sector. Under the new Blended Retirement system, active duty personnel are offered retirement plans operating similar to the 401K plans in the private sector.

Instead of only offering active duty personnel retirement benefits if they serve a full 20 years, the portability of the blended system can be used as a recruiting aid, Spencer said while speaking at a recent event at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Spencer developed the blended retirement system idea while a member of the Defense Business Board.

With the ability to take some retirement savings from time spent in the military into the private sector, the thinking is active duty personnel might be encouraged to remain in the service longer than their initial commitment — maybe not a full 20 years, but more than an initial tour of three to five years.

At the same time, Spencer says allowing active duty personnel to leave early with some retirement benefits opens the service to competition from the private sector. The potential exists for mid-career officers and senior enlisted to leave active duty earlier than maybe they would have considered under the 20-year pension system.

“I truly believe the blended retirement system is a benefit that is going to draw people into the service,” Spencer said.

Meanwhile, acknowledging new recruits will not be enough to fulfill staffing needs, the Navy is also making it harder for sailors to leave active duty early.

In the past few months, along with canceling early retirement programs, the Navy has tweaked other personnel policies, apparently designed to keep sailors in the service longer by reducing the ways they can leave. The Navy also just changed its Physical Readiness Program separation policies. Sailors who fail their physical readiness tests can remain in the Navy but will not be able to advance in rank until they pass the test or their commitment is over.

“It has been decades since the last period of major personnel growth in our Navy. You will see many additional policy changes in the coming weeks and months to set us on the right course,” Burke said in his December instruction.

About the Numbers

USNI News reviewed several data sources to estimate the end strength totals, the number of sailors currently serving aboard ships, and predicted needs in the future.

Navy End Strength

Historical and current Navy end strength numbers were provided by the Navy to USNI News. Projected annual end strength totals – the Navy’s goal for each year – are included in each fiscal year budget request.

Current Navy Staffing Aboard Ships

When determining the number of sailors currently serving aboard ships, USNI News multiplied the number of ships in each class by the typical crew size for these ships, then added the totals from each class to arrive at the final estimated total of 111,606 sailors currently serving aboard ships in the Navy’s currently stated 282-ship fleet.

The USNI News estimated total current ship-based staff is based on crew levels stated on Navy fact sheets about each class of ship. In some cases, USNI News relied on previous reporting of crew levels since sometimes crew sizes are not the same those stated on legacy Navy fact sheets.

For example, the Navy fact sheet lists the crew size of an Arleigh Burke-class of guided missile destroyer as 329 sailors, when currently the crew size is generally closer to 270 sailors. Similarly, the Navy fact sheet lists the crew size of a Ticonderoga-class guided missile cruiser as 330 sailors, also more than the current estimate of close to 270 sailors.

Future Staffing Aboard Ships.

Since future staffing needs on ships being built may differ from current crew size, the USNI News estimate is an educated guess based on the current staffing for each class of ship being built.

The Navy currently has 56 hulls in various stages of construction or planning, due to be completed during the next decade. We subtracted the new Virginia-class submarines from this total because they are due to replace both the Ohio-class guided missile submarines and Los Angeles-class submarines as they retire. Two new Ford-class aircraft carriers are expected to join the fleet, but USNI News anticipates the Navy retiring two older Nimitz-class aircraft carriers. In these cases, the USNI estimated these actions would not dramatically change staffing needs.

To arrive at the additional personnel needed to staff ships being built, USNI News only counted ships not expected to replace existing hulls — 39 currently being built or planned to be built. USNI News multiplied by the number of ships in each class still being built by the typical crew size for these ships then added the totals. Included in this estimate are the following numbers of each type of ship class: 1 America-class (LHA-6) Amphibious Assault Ship; 2 Zumwalt-class guided missile destroyers (DDG-1000s); 4 San Antonio-class (LPD-17) Amphibious Transport Docks; 12 Arleigh Burke-class (DDG-51s) guided missile destroyers; and 18 Littoral Combat Ships (LCS-1, LCS-2). Two Puller-class ESB-3 Expeditionary Mobile Bases are being built, but crews are a hybrid of military and civilian mariners, so staffing for these ships was not included in USNI News calculations.

Long-Term Staffing Aboard Ships.

When considering long-term staffing needs, USNI News’s finding was very close to a recent report issued by the Congressional Budget Office, which predicts the Navy would need about 125,000 ship-based sailors by 2047 to crew a 355-ship fleet. USNI News is using the CBO number, which is based on some best-guesses because the ultimate mix of ships in the future fleet is not known.