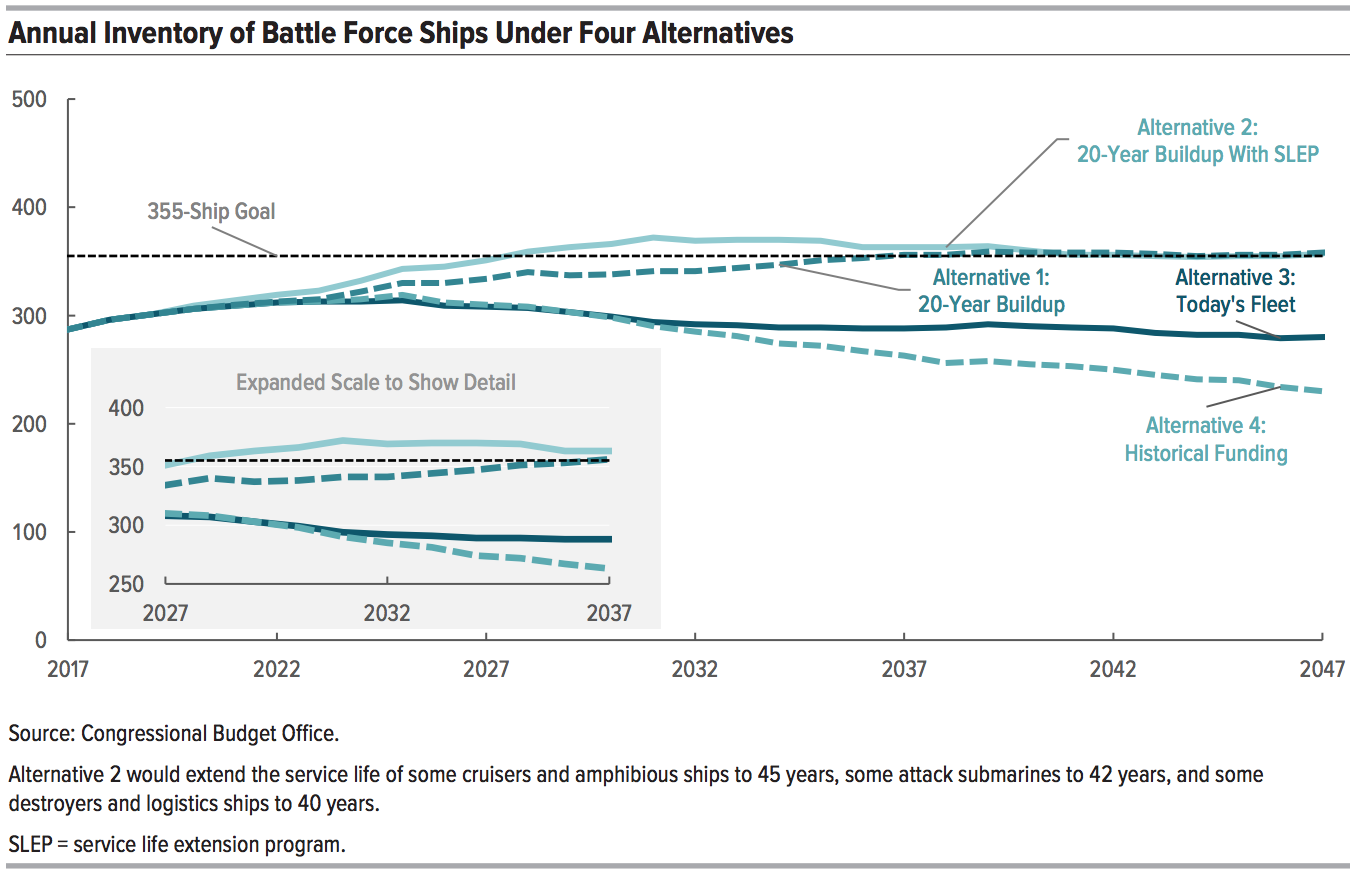

Two of four shipbuilding scenarios detailed by a Congressional Budget Office report released Wednesday would create a 355-ship Navy by 2037, but current Navy spending requests only maintain the status quo of the current-sized 282-ship fleet.

Starting in the current Fiscal Year 2018, and continuing for the next five years, the Navy proposes in its 2019 Budget to spend an average of $20.8 billion a year on shipbuilding – an amount, according to CBO calculations, that wouldn’t pay for maintaining the status quo of current fleet size of 282 ships, let alone pay for a fleet size increase.

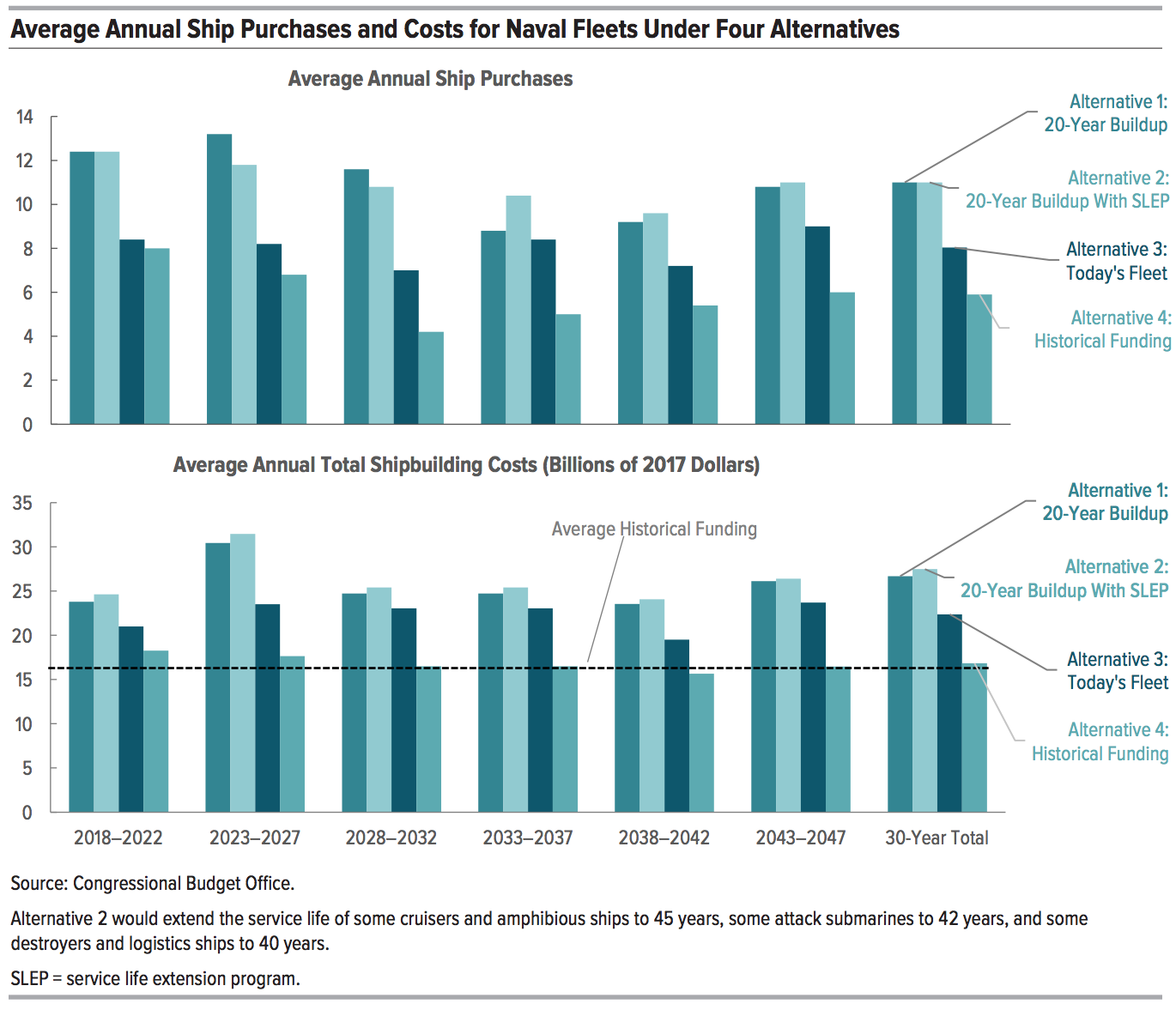

In four scenarios, the CBO report offers lawmakers variations of proposed shipbuilding plans to consider funding for the next three decades. Building a 355-ship fleet, according to the CBO, would require buying 330 new ships for the next 20 years and spending between $103 billion and $104 billion to maintain this fleet through 2047.

“The president’s budget only allocates $20 billion to shipbuilding and proposes to build 10 ships. We must get to 13 ships and increase the budget accordingly,” said Rep. Rob Wittman, (R-Va.), chair of the House Armed Services seapower and projection forces Subcommittee, in a statement released last week before a hearing on the Navy’s shipbuilding plan.

The CBO’s report suggests funding level of $26 billion per year would strike the “sweet spot” to build a 355-ship Navy, added Wittman, who also co-chairs the House of Representatives shipbuilding caucus.

Concentrating on buying new ships, the CBO reports, would require the Navy to add between 12 and 13 new ships each year, spending an average of $26.7 billion annually on shipbuilding.

If the Navy extended the lifespan of some ships near retirement age, the CBO reports a 355-fleet could be achieved quicker but would not provide the Navy with an ideal mix of ships for several years. The Navy’s shipbuilding pace would start off slower, between 11 and 12 new ships annually, at first, and require spending an average of $27.5 billion per year. The slightly higher annual price includes the cost of extending the life of existing ships.

“Those figures are more than 60 percent higher than the amounts the Navy has spent on shipbuilding over the past 30 years and more than 25 percent higher than the amount appropriated for 2017,” the CBO report states.

Just maintaining the status quo, keeping a future fleet at a size comparable to the Navy’s current 282-ship fleet, will still require buying new ships to replace those being retired from service. This plan would require average annual spending of $22.4 billion on shipbuilding, still more than what the Navy proposes spending on shipbuilding in FY 2019.

Maintaining the fleet of 282 ships for 30 years would cost an estimated $91 billion-per-year, because the costs associated with building new ships and keeping ships at sea are still expected to increase, according to the CBO analysis.

“Pay for military and civilians is projected to increase faster than inflation as are costs to supply and repair the Navy’s ships,” the CBO report states.

Lawmakers could also decide to essentially do nothing by capping funding for the Navy’s annual shipbuilding plan to what the CBO report described as an average of historic funding levels. However, even this option comes with steep costs, requiring $82 billion-per-year to maintain the fleet for the next 30 years, and would likely result in a fleet of 230 ships by 2047 — down from the current total of 282.

Opting for a smaller fleet would likely reduce the nation’s shipbuilding capacity, the CBO reports. Limiting funding to historic levels would only require slightly more than five ships being built per year, which is less than one ship per existing shipyard.

“It is not clear whether that would be enough business to keep all seven yards open, although if it were, the workforces in those yards would shrink to reflect the reduced activity,” the CBO report states.