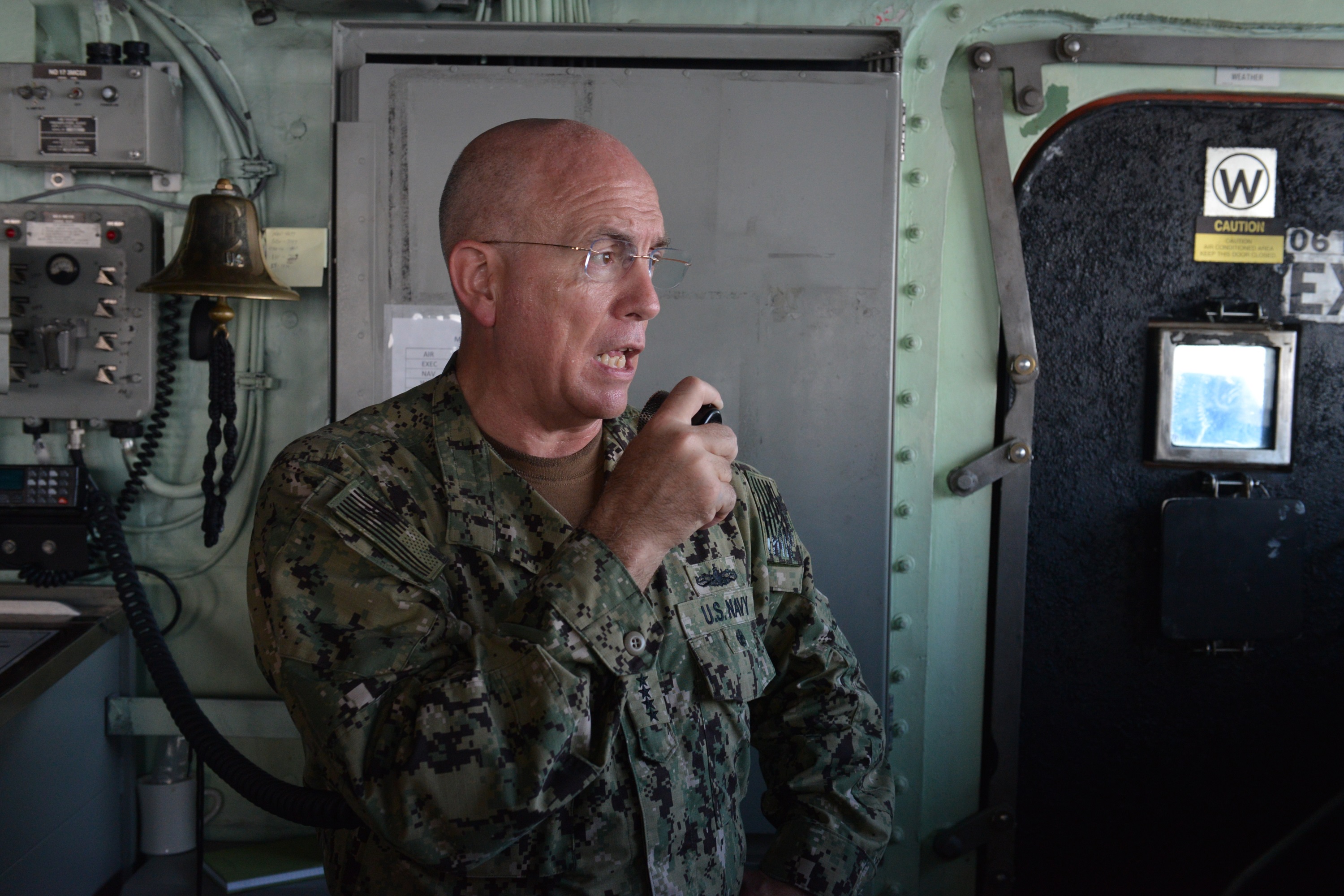

Rather than concentrating on cutting off goods moved via illegally trafficking – people, cocaine, opioids, gold, exotic animal and plants – U.S. Southern Command and its national partners are now looking at the best way to disrupt the criminal networks that control that flow, SOUTHCOM commander Adm. Kurt Tidd said at a Coast Guard Academy leadership event Tuesday.

During his keynote, presented by the U.S. Naval Institute, Tidd said gone are the days when the combatant command was identified as “the guys who do drugs.” The idea now is to address the broader security challenges where criminal network activities blur into terrorist activities. To disrupt those networks means using classic military skill sets, law enforcement expertise and intelligence professionals to meet the mission.

SOUTHCOM’s switch from tactical to strategic means a mission to “detect, illuminate, disrupt” criminal activities, while including and supporting law enforcement and judiciary of regional partner nations.

Earl Anthony Wayne, a former U.S. ambassador to Mexico, said at the same event that Mexico sees the value of this approach to deal with its own security struggles and the challenges it faces from migrants crossing from Central America and drug trafficking through the region.

Wayne added that when the Mexican government began cracking down on the drug cartels, it soon realized its national and local police weren’t ready, so it turned to its military. The army then was focused on humanitarian missions and the navy functioned more as a coast guard, so they also had to be trained for the new mission.

“The military had to learn a whole new set of procedures,” including when to shoot or when to hold fire to avoid unnecessary casualties, Wayne said.

Even inside the narcotics trade, Tidd said the emphasis has switched from cocaine to heroin, and from drugs from Mexico to synthetics from China.

But the real source of new profits is coming from illegal gold mining in Peru, Colombia and Guyana. Tidd described the cartels using a slurry process with mercury to extract the ore, with the landscapes “looking like the back side of Mars” when the cartel’s workers are done. The biggest benefit to the cartels is that once the gold leaves the country where it was mined, “it’s legal.”

Tidd said Colombia estimated cartels there are clearing $3.5 billion in illegal gold mining versus $2 billion in cocaine a year.

Regardless of which commodity generates the cartels’ profits, “the problem of corruption” in law enforcement and the judiciary are still real in these nations, and as a result, “the military is often called in” to deal with the cartels, Tidd said.

The cartels “create very large zones of influence” inside these nations, not just geographically but politically because of the profits. The continuing demand for narcotics in the United States complicates the problem of hurting the cartels and networks outside its borders.

“We buy the stuff,” Tidd said, estimating that $19 to $20 billion in illegal drug sales comes from the United States.

“That buys a lot of officials and arms.”

Building trust among partner nations and creating true jointness of operations in disrupting the networks is the way to succeed, Tidd and Wayne agreed.

Tidd said there are four steps the SOUTHCOM is taking to build partner capacity with this new strategic approach. First, military and police forces must understand the value in respecting human rights. Second, ”you must have a professional NCO (non-commissioned officer) corps” to maintain standards and be effective. Third, they are trying to harvest talent from all communities, including male and female personnel of all social and economic standings. And lastly, they are working to apply true jointness – including military, law enforcement, intelligence and diplomatic communities – to the challenge.

“We have the best chance of success of working jointly” with Mexico and other Latin American nations, Wayne said.

Several times, the two were asked what it would take in interdictions to have an impact on narcotic trafficking. The answer lies in eliminating demand in the domestic market, both said. In terms of more assets, Tidd said it was very unlikely that the Navy could provide more ships to help with interdictions and still meet its commitments to other combatant commands.

“You’re in the situation where you rob Peter to pay Paul … We’ve just got to be more creative” in going after the networks, Tidd said.

As the event was ending, Wayne was asked about President Donald Trump’s promise to build a border wall between the United States and Mexico to cut down the flow of illegal immigrants and narcotics. The diplomat said that would be a “waste of resources.” He said that belief is shared among many working in homeland security even if they cannot speak publicly on the question.

He acknowledged the numbers of illegal crossings are significantly down, in part due to the rhetoric about what will happen if an illegal entrant is captured.

There are “certain places where a wall makes sense” along parts of the border, but a better investment would be in technology, such as “a smart wall with sensors,” Wayne said, adding, “that is different than what you did with a wall.”

Working together with the Mexican government to install in-depth layers of security sensors with mobile response forces on both sides of the border would be effective in cutting down illegal crossings.

“We sure have the technology to get eyes on them and then intercept,” Wayne said.