The Navy released a new fleet plan that calls for 355 ships, outlining a massive increase in the size of its high-end large surface combatant and attack submarine fleets but a modest increase in its planned amphibious ship fleet, according to a Dec. 14 summary of the assessment.

The findings of the latest Force Structure Assessment adds 47 ships to the Navy’s battle force over the 308-ship figure from a 2014 FSA.

According to the summary, the service determined the 355 total was the “minimum force structure to comply with [Pentagon] strategic guidance” and was not “the “desired” force size the Navy would pursue if resources were not a constraint, read the summary.

“Rather, this is the level that balances an acceptable level of warfighting risk to our equipment and personnel against available resources and achieves a force size that can reasonably achieve success,” according to the summary, which notes it would take a 653-ship force to meet all global requirements with minimal risk.

The largest change to the 2014 totals are in the high-end ships classes of attack submarines, large surface combatants – like guided-missile cruisers and destroyers – and aircraft carriers. The new total adds 16 large surface combatants, 18 attack submarines and an additional carrier over the 2014 plan.

Since the roll out of the 2014 plan, both Russia and China have adopted a more expansionist stance and accelerated developments of high-end weapons systems – including supersonic anti-ship missiles and more sophisticated anti-submarine warfare platforms and networks. Service officials expressed increased concerns over the last two years and have told USNI News the force from the 2014 FSA would be insufficient to handle the developing threats.

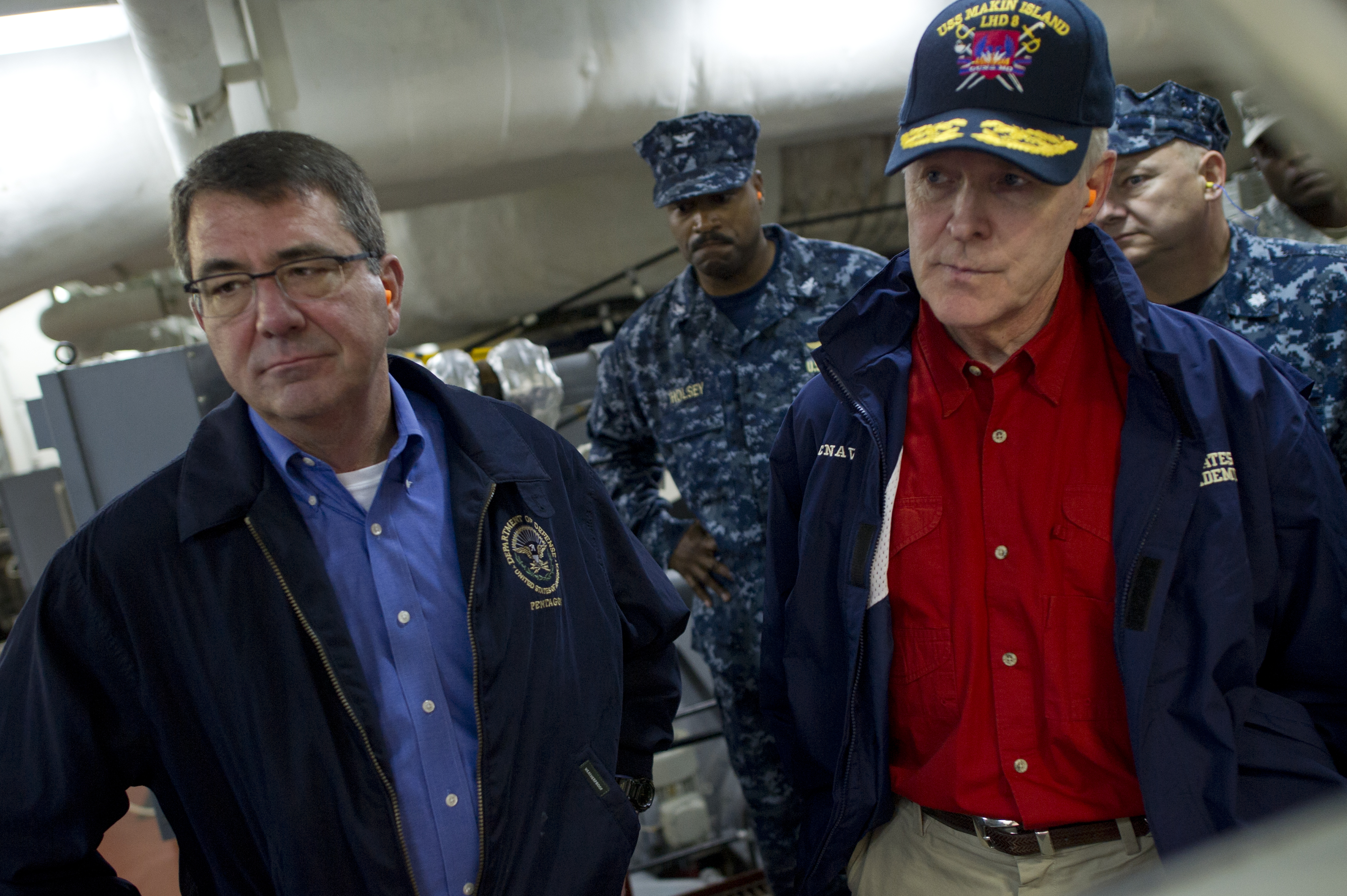

There are also political implications for the new number and the timing of the release. The new total comes as Navy Secretary Ray Mabus and Defense Secretary Ash Carter have engaged in a public spat over the direction of the Navy’s shipbuilding program, and as the Trump administration prepares to take office and potentially begin moving towards its stated goal of building a 350-ship Navy.

Large Surface Combatants

The uptick in large guided-missile ships are to “deliver increased air defense and expeditionary [ballistic missile defense] capacity and provide escorts for the additional aircraft carrier,” reads the summary.

Last year, USNI News reported the surface Navy was increasingly concerned with the speed and sophistication of new anti-ship guided missiles emerging from China. Officials worried the service’s assumption of 88 large surface combatants was too low.

That total was based on filling a carrier strike group with five guided-missile combatants to perform anti-submarine warfare (ASW), protect the ship from surface and air threats and protect the CSG from ballistic missiles.

However, ongoing studies and wargaming conducted by the Navy’s surface warfare establishment concluded the number of ships to keep carrier safe should potentially be increased to seven or eight due to how rapidly the Chinese have increased their high-end capability.

What’s unclear from the summary is how the Navy will organize the large surface combatant total.

The Navy has struggled with finding both the money and time to modernize the Aegis Combat Systems in its legacy Arleigh Burke-class destroyers to configurations that can simultaneously fight traditional air warfare threats like cruise missiles and fighters as well as ballistic missile threats.

Additionally, it remains to be seen if the service will revise its cruiser modernization plan that sidelines some number of the ships, if the service will accelerate a new cruiser replacement program, and if it will accelerate production of the existing class of Arleigh Burke guided-missile destroyers from the current two-a-year pace split between General Dynamics’ Bath Iron Works and Huntington Ingalls’ Ingalls Shipbuilding.

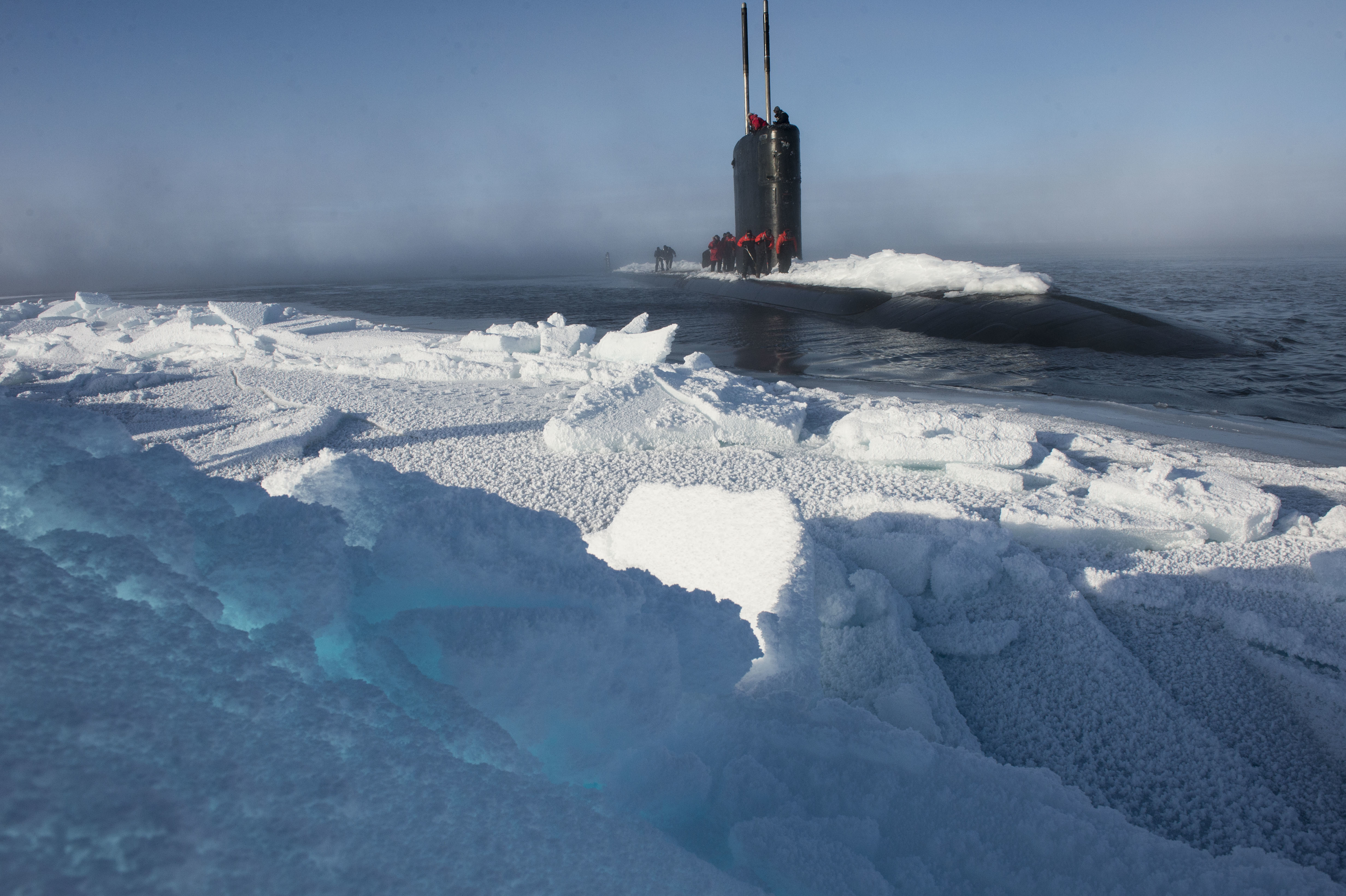

Submarines

The Navy now intends to build to a force of 66 attack submarines, up from about 50 SSNs today and stated requirement for 48, to “provide the global presence required to support national tasking and prompt warfighting response.”

A large increase in the attack submarine requirement was expected. Over the past year, the U.S. Pacific Command and U.S. European Command commanders have told Congress that they are only receiving about 60 percent of the SSN presence they request, in a time when Chinese and Russian submarine activity is increasing and anti-ship missile threats are both growing more sophisticated and proliferating. Attack subs may be the best naval tool for early battlefield shaping efforts, were the U.S. Navy to enter into a conflict, and the Navy has plans to make the current Virginia-class attack subs more lethal and stealthier through planned block upgrades.

Based on the combatant commanders’ testimony, it would take a fleet of at least 80 SSNs to fill all their requests, which would be unfeasible for the submarine shipbuilding industry – which consists of two yards, General Dynamics’ Electric Boat and Huntington Ingalls’ Newport News Shipbuilding – given the start of construction activities for the new Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine replacement program.

Though 66 would not give the combatant commanders everything they want –the Navy acknowledges in the FSA’s executive summary that the service will never be able to build enough to give the combatant commanders’ their full requests – it would go a long way in giving the Navy more options for realistic high-end training with live submarines ahead of carrier strike group deployments, mid-deployment training opportunities at sea and increased presence to counter increased Russian and Chinese presence.

The Navy’s new FSA does not make any changes to the service’s requirement for nuclear weapon-carrying ballistic missile submarines. The Navy has 14 Ohio-class SSBNs today and intends to replace them with 12 Columbia-class boats that can provide the same level of presence.

Aircraft Carriers

The new plan calls for adding one additional aircraft carrier to the Navy’s force structure, bringing the service total to 12.

A carrier strike group is among the most in demand assets from the U.S. combatant commanders for its imposing conventional deterrent and its ability for the U.S. to conduct strike operations almost anywhere in the world. The Navy today has 10 and will have 11 when the first-in-class Gerald R. Ford joins the fleet next year, though it will not begin overseas deployments until it finishes a couple years of post-delivery tests, shock trials and maintenance work.

The Navy’s 10-carrier fleet has struggled to balance maintenance needs and combatant commander demand. The Navy tried to move to a supply-based deployment model with its Optimized Fleet Response Plan but has still seen carrier deployments extended to avoid gaps in carrier presence in the Middle East and the Pacific. As a result, presence has varied wildly in the last couple years: over the summer the Navy had two carriers in the Mediterranean and two operating together in the Philippine Sea, and yet today only one carrier is in the Mediterranean and none underway in the Pacific.

An additional carrier could provide additional overseas presence, but it could also provide a buffer to ease pressure on the force, allowing ships sufficient time for maintenance and training.

Only one shipyard, Newport News Shipbuilding, builds aircraft carriers. The yard currently builds the carriers in five-year centers, though the shipyard and its supporting vendor base have argued it would be more efficient to deliver a carrier once every four years. For the Navy to increase its carrier fleet size, it would have to build the ships faster than they are set to decommission, and moving to four-year centers is the most likely way to do that.

Amphibs

The new FSA calls for 38 amphibious ships, which is up from today’s requirement of 34 and today’s actual fleet of 31 ships, but not nearly as large an increase as many in the Navy and Marine Corps had hoped for.

The Navy and Marine Corps agreed several years ago that it would take 38 amphibious ships – and a particular balance of fixed-wing capable amphibious assault ships (LHDs and LHAs), sophisticated San Antonio-class amphibious transport docks (LPDs) and workhorse dock landing ships (LSDs) – to support a two-Marine Expeditionary Brigade forcible entry operation. They also agreed that despite the need for a two-MEB force, they could not afford 38 ships in the current budget environment, so they would aim for 34 as a budget-constrained figure.

Requirements for Marine Corps presence around the world has only increased since that agreement. The service has sent out land-based Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Forces (SP-MAGTFs) to provide presence in Africa, the Middle East and South America. Without ships, though, these forces rely on their MV-22 Ospreys and KC-130J Super Hercules aircraft to move around – and importantly, they rely on the permission of other nations for basing and other support, rather than being self-supported from a U.S. warship at sea.

In addition to the SP-MAGTFs, the 3rd Marine Division in the Pacific is located forward in Japan but does not have any ships it can access regularly to for training, partnership-building with local Pacific partners or to respond to a contingency.

In total, the Marine Corps has said it would need upwards of 50 amphibious ships to provide the presence around the world it provides today but with proper amphib ship support.

Small Surface Combatants

The new total also restores the Navy’s old 2012 requirement of 52 smaller surface combatants, which will include the Littoral Combat Ship and frigate programs.

Last year – on Dec. 14, 2015 – Carter ordered the Navy to trim the LCS and frigate program to 40 ships from 52 and route the money into higher-end weapon systems.

Carter issued a terse directive that chided Mabus’ shipbuilding priorities and accused the department of promoting shipbuilding “at the expense of critically-needed investments in areas where our adversaries aren’t standing still… this has resulted in unacceptable reductions to the weapons, aircraft and other advanced capabilities that are necessary to defeat and deter advanced adversaries.”

Uniformed officials have continued to say at events and in congressional testimony that, though Carter may have curtailed the small surface combatant program at 40, the warfighting requirement remained at 52.

Since the 2015 memo, the LCS program has come under sustained scrutiny from Congress, and the both the Lockheed Martin Freedom-class and the Austal USA Independence-class variants have suffered high-profile engineering failures.

In September, the Navy rolled out a new plan that restructured the deployment of both classes of LCS, but given the continued criticism of the program it’s unclear what further changes may need to be made.

Also unclear, based on the restored 52-ship requirement, is whether the Navy will transition to the frigate with both or just one LCS hull design. The service originally intended to make frigate upgrades to both the Freedom-variant and Independence-variant designs, adding survivability and lethality and permanently installing both surface warfare and anti-ship warfare equipment rather than using interchangeable mission packages. Carter’s memo last year not only directed the Navy to stop at 40 LCSs and frigates but also instructed the service to downselect to a single vendor for the frigates. The Program Executive Office for LCS told USNI News recently that it crafted its latest request for proposals in a flexible way that would allow the office to buy a range of numbers of LCSs or frigates from either or both yards, depending on what the next administration directs it to do.

Auxiliaries

The FSA calls for the Navy growing its Combat Logistics Force by three ships, its Expeditionary Support Base (formerly called the Afloat Forward Staging Base) by three and its command and support ships by two.

The executive summary notes the combat logistics ships are needed to support an additional aircraft carrier and the larger fleet of large surface combatants, which require refueling and resupplying at sea. The increase in command and support ships reflects two additional surveillance ships.

The doubling of the ESB fleet comes as only one has joined the fleet but Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. Robert Neller has said the combatant commanders are already clamoring for more. The Navy converted an LPD set for decommissioning into an interim AFSB in 2012 to support mine countermeasures operations in the Persian Gulf. The resounding success of that deployment led the Navy to convert its Expeditionary Transfer Dock (formerly called the Mobile Landing Dock) design into an ESB that could support mine countermeasures operations, special operations forces and even Marine SP-MAGTF operations.

Neller said in February that the first ESB, USNS Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller (T-ESB-3), would deploy to the Middle East but that he wanted a ship like that in the Mediterranean Sea to support the Europe-based SP-MAGTF crisis response force that covers Africa.

“I would like very much for that ship to be based in the Med. Right now that’s not the plan, but we’re going to continue to work on that,” he said at a Brookings Institution event. “The COCOMs, both AFRICOM and EUCOM, have written a letter saying hey we’d like to have this capability in the Med to service West Africa and the Med because there’s stuff going on there that we need to be able to move around. You don’t want to be tied to a land base.”

The 3rd Marine Division in the Pacific has also expressed interest in an ESB if it couldn’t get access to amphibious warships, as an alternate means of being able to move its force around the Pacific. Adding three additional ESBs to the plan could help fill these requests for ESBs in the Pacific, Mediterranean and Gulf of Guinea areas.

The Politics

The release of the new set of shipbuilding goals comes as Mabus and Carter are locked in a public fight over shipbuilding priorities.

Earlier this month, the Navy submitted its proposed Fiscal Year 2018 budget that included $17 billion in additional spending in open defiance of guidance from Carter, as first reported by Defense News That money would buy surface ships Carter ordered trimmed as well as additional submarine, Defense News reported.

In a memo, Mabus chided Carter’s direction.

“The instruction your office conveyed directed cuts that would reduce the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ essential role as a forward-deployed and forward-stationed force to a fleet confined to home ports with infrequent overseas deployments,” Mabus wrote in the memo.

“In order to build some types of ships, I will not cut other ships, regardless of their function in the fleet. That is not how you maintain a Navy, one of our nation’s most precious assets.”

The timing of this FSA is unusual, since it typically follows the submission of the entire defense department budget to Congress every few years.

The release, almost two months ahead of the full budget release to Congress – and several months after the planned Summer 2016 rollout – is thought to be a move from Mabus to cement his shipbuilding legacy over Carter’s objections. It could also support the incoming Trump administration that has called for a battle force total of more than 350 ships.

“My budget submission will be the bridge to future budgets that reflects a new Force Structure Assessment and builds the Navy and Marine Corps the nation needs to maintain American influence, assure allies and partners and protect critical pathways of trade and commerce,” Mabus wrote in the December memo. “If you ultimately decide to submit a budget that takes away the ability of the Navy and Marine Corps to do their job, it will not have my support, and I will make my objections widely known.”