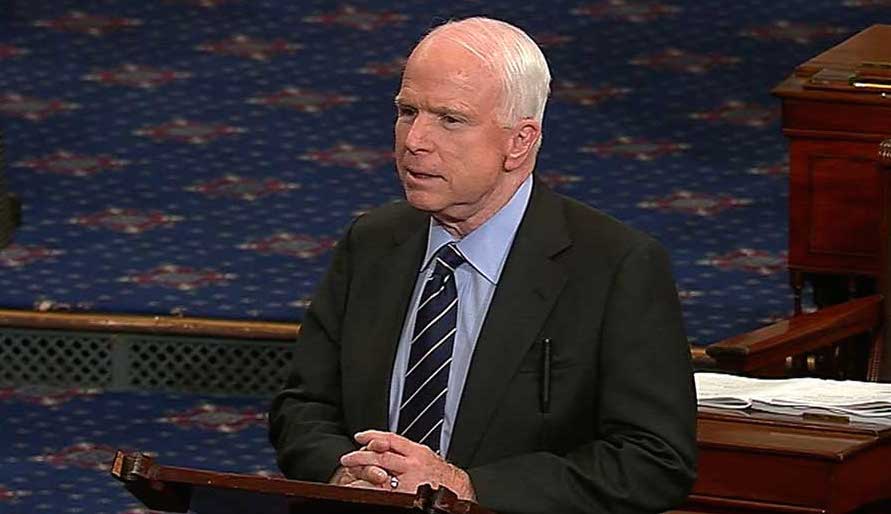

Sen. John McCain warned Google and Apple executives Thursday that the Senate Armed Services Committee “has subpoena power” that could compel them to testify on why their encryption systems on newer smartphones are not accessible to law enforcement operating under court orders.

The Arizona Republican, who chairs the panel, said, “There’s an urgency” to finding a solution to the matter of protecting privacy while also not closing out police, prosecutors and intelligence agencies from lawfully pursuing criminals and terrorists.

At the start of the hearing, McCain noted that Tim Cook, president of Apple, declined to attend the session. “This is unacceptable,” he noted of Cook’s reluctance to appear, as the hearing neared its end.

Sen. Jack Reed, (D-R.I.) and ranking member, said, reaching an agreement on this issue is “something that cannot take forever” while noting figures such as Michael Chertoff, former secretary of Homeland Security; Gen. Michael Hayden, former CIA director, and others have come down on the side of the companies’ positions regarding users’ privacy.

McCain indicated at the hearing, the second on cyber encryption that he has called, he was leaning toward passing legislation rather than establishing a commission to study the issue. One proposal in the Senate is to have the commission make a recommendation back to Congress and the administration within a year or 18 months.

Speaking as a former assistant attorney general in the George W. Bush administration, Kenneth Wainstein said, prosecutors “have to submit to lawful court orders” and so should Apple, Google and others who include that kind of security feature on their devices. It is “up to Congress to make that point legislatively.”

Referring to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, where law enforcement agencies and the intelligence community did not share information, “we made the mistake of inaction” in not working together and with the private sector.

Cyrus Vance Jr., district attorney for Manhattan, told the committee, “The fact of the matter is [an earlier version of iPhone] was extremely secure.” But in the wake of the revelations from Edward Snowden on the surveillance activities of the National Security Agency, Google and Apple developed operating systems where encryption was embedded to address privacy concerns and said not to be available, even to the manufacturer, through a backdoor.

That encryption feature took on new urgency for law enforcement and intelligence agencies in the wake of the San Bernardino terrorist shootings when local police and the FBI could not access what was on the phone taken from the Syed Farook, who was killed in a shootout.

In short, the device’s security works this way: the user has a four letter or digit pin, but after 10 failed tries to access the data is wiped clean. The FBI eventually paid hackers over $1 million to gain access to the phone’s data.

While there are legitimate concerns about privacy from users and proprietary information from manufacturers, Wainstein said it was up to the companies to show “how this damage will occur.”

John Inglis, a former NSA deputy director and now a professor at the U.S. Naval Academy, said the technology is likely available to address concerns from users and the manufacturers and the government.

“We must establish the overarching goal before enacting laws,” he said.

Vance said most criminals do not actively encrypt their communications, but that security feature already in place blocks law enforcement and prosecutors from gathering evidence in cases ranging from child pornography to murder. He added that his office has more than 300 phones with that feature in its hands but the data on them are not accessible to building cases. He decribed the companies’ position regarding this inaccessible data as “simply acceptable collateral damage,” even in criminal cases.

Sen. Angus King, (I-Maine), said while the encryption horse is already out of the barn because it is in place, “this should be a legislative solution.” He encouraged the witnesses to send additional comments to the committee as it moves forward to its next hearing on cyber security.