The Marine Corps is moving towards a future in which small dispersed units can protect themselves from incoming enemy drones with laser weapons and from missiles and aircraft with Stinger missiles, with both weapons netted into a detection system and mounted atop Humvees, Joint Light Tactical Vehicles and other combat vehicles.

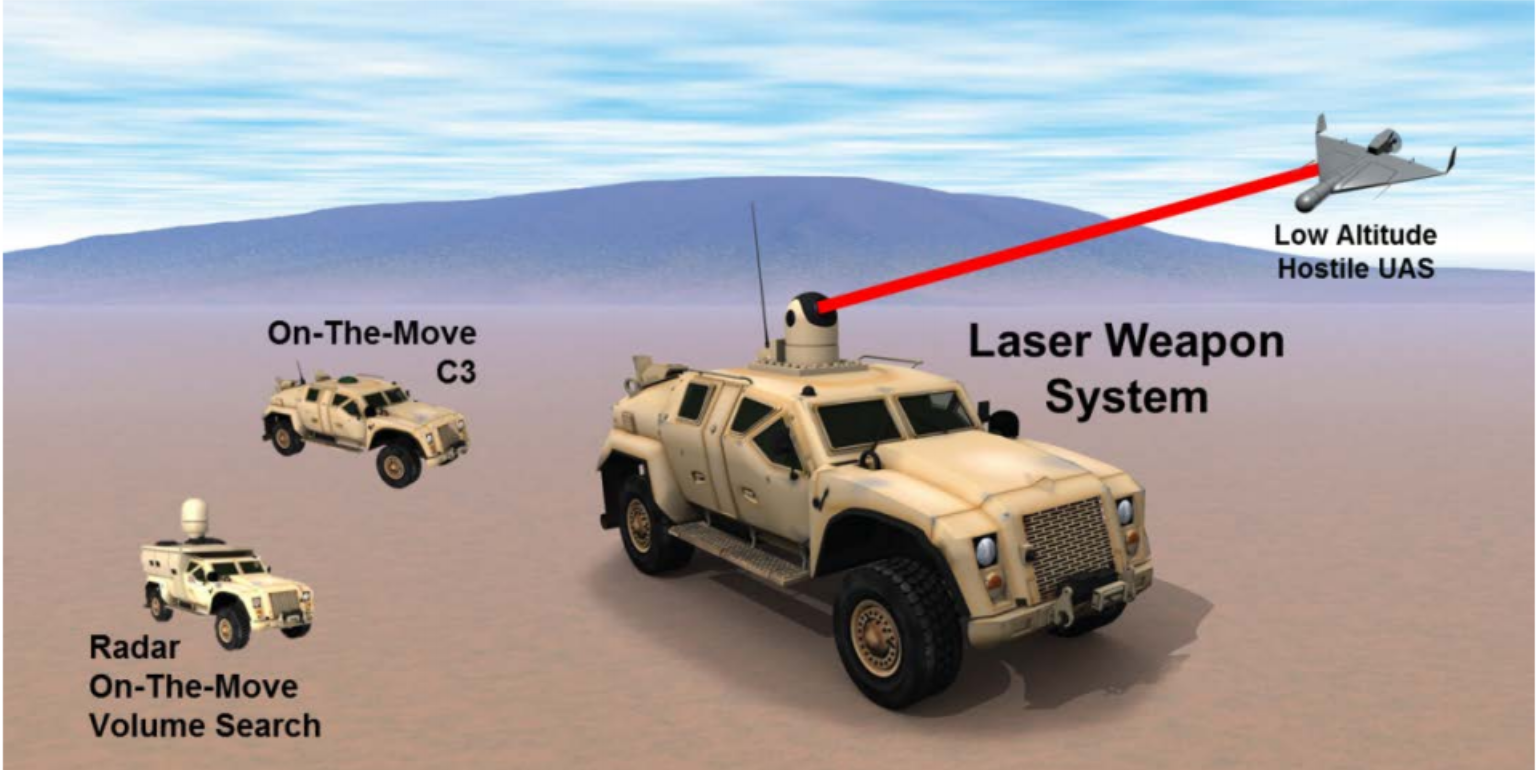

Lt. Gen. Robert Walsh, deputy commandant of the Marine Corps for combat development and integration, said a Ground-Based Air Defense (GBAD) Directed Energy On-The-Move concept demonstrator with the Office of Naval Research is nearing the start of Phase 3, moving from firing a 30-kilowatt laser at a target from atop a stationary ground vehicle to firing while on the go. Upon completion of the ONR program, around 2022, the GBAD DE OTM system would transition into a program of record in the Marine Corps and likely reside alongside the Stinger missile system as a ground unit self-protection system – giving those units a much-needed upgrade after operating with the Stinger for decades.

Walsh said the Marines operated in a permissive environment in Iraq and Afghanistan for 15 years, “but when we see near-peer competitors, the development that’s going on in Russia and China, it is really waking us up to what we’re going to have to do in the future,” noting the concepts of operations and requirements for future systems are already evolving rapidly to keep up.

“So we look at our air defense capability as certainly a weak area that we have not upgraded in a long time because we haven’t had to deal with that in the operating environment we’ve been in,” he told the audience at the second-annual Directed Energy Summit, cohosted by Booz Allen Hamilton and the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment.

In the short term, the Marines are fielding the new Ground/Air Task Oriented Radar (G/ATOR) to detect incoming threats and the Common Aviation Command and Control System (CAC2S) to integrate all the data into a single operating picture. That data will be pushed to the the Direct Air Support Center (DASC), who could in turn give low-altitude air defense (LAAD) batteries specific information about incoming threats.

“Get them the feed so they can see it, now they know the target is coming and they can shoot it with a Stinger, compared to now where the Marines send someone out with binoculars to look for threats in the air, Walsh told reporters after his conference presentation.

“But the laser would tie right into that,” Walsh said, noting that the GBAD DE OTM laser system could be installed alongside the Stinger launcher, giving the LAAD batteries the option of using the laser for smaller threats – Group 1 through 3 unmanned aerial vehicles, for now – or using the missile for high-altitude UAVs, cruise missiles or manned aircraft.

“Eventually if you could transition away from the missiles to go directed energy-only, we would do that” if the laser technology improved sufficiently, he added.

The Army is also pursuing a mobile laser weapon, and Walsh said that though their efforts are separate for now, “once we see where we’re coming out of that, working closely with the Army, we see ourselves paralleling into a joint program of record on this.” The hope is that this joint program could push the Marines’ current 30kw laser into something smaller and more powerful, enabling it to take on larger UAVs and eventually rockets, artillery, mortars or even larger threats.

The Army is also pursuing a larger base-defense laser weapon. The Marine Corps will not participate in that development program, as the service is focused on mobile systems for dispersed ground units, but if the Army succeeded in fielding a program the Marines could consider buying the system for stationary forward operating bases as needed, he said.

On the aviation side, Walsh said there is already directed energy as a self-protection tool included in the Directed Infrared Countermeasures (DIRCM) system on the CH-53 to fight off incoming threats. DIRCM will eventually be fielded on the H-1 helicopters and V-22 Ospreys. For offensive purposes, Walsh said the KC-130Js will be outfitted for the Harvest Hawk weapons capability and adding in directed energy weapons may be a natural follow-on.

Walsh said that DIRCM is fielded now, counter-UAV lasers are getting close and counter-artillery lasers are farther out, but all the technologies are maturing well. What he’d like to see next is a field exercise to “get comfortable with the technology, and I think everything is moving to how quickly can we get out there and use it. And I would push, from my standpoint with the commandant would be, let’s look at what the Navy did with Ponce,” Walsh said, referring to the USS Ponce (AFSB(I)-15), the converted afloat forward staging base that hosts the Navy’s Laser Weapon System (LaWS).

“Now, people will say that’s a different environment, it’s over water, it’s not over land where you might have collateral damage and things like that,” Walsh told reporters.

“We could work through those things, and the Navy’s kind of broken some trail on that already with Ponce, so I think we’d be willing to get that out, obviously experiment with it, and then get it out there and field it and see where we go.”