Although China and Russia have certainly grown closer in the last several years, their relationship is a marriage of convenience since for both their most important international relationship is not with each other but in dealing with the United States.

Speaking Thursday at a forum at the Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C., think tank, Chisako Masuo, an associate professor at Kyushu University in Japan, said, “So far, the Russia-China alignment is strong, but not robust.”

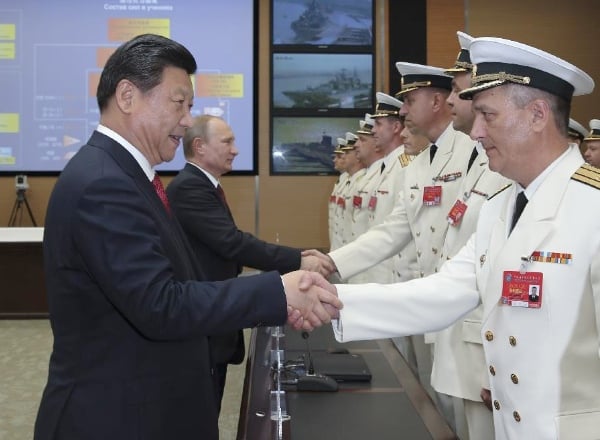

To Moscow, “China is its only reliable friend.” China has also become a huge trading partner. Helping Moscow’s military industrial base, Beijing recently bought advanced missiles and aircraft from Russia to better project power from its own shores.

But signs of fraying in the relationship are particularly evident, she said, in Central Asia where Russia historically has played the dominant security role. Now China is playing an increasingly important economic development role through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in these former Soviet republics.

David Gordon, of the Eurasia Group, added, “More and more Russia finds itself in a junior role” in the relationship with Beijing as China flexes economic strength. It is a time where there are “ample arenas for cooperation and competition” between the two.

Russia and China were brought closer together in 2014 after Moscow’s annexation of Crimea and military support of separatists in eastern Ukraine brought tough economic sanctions from the United States and the European Union and a subsequent series of agreements to sell natural gas to Beijing.

“That hedge has not worked out very well,” Gordon said.

While “energy issues continue to influence the relationship,” cooperation between the two “has begun to founder.” Gordon said that Russia never did receive the large Chinese investments in energy production is its far east and northeastern regions or the building of new pipelines through Central Asia that it expected.

As a result, “Russia is coming to terms” with its “continued dependence on European markets” to keep its economy afloat .

In short, “Russia is increasingly wary of becoming a resource appendage of China.”

Akihiro Iwashita, a professor at Hokkaido University in Japan, said Russia and China finally realized after years of border conflict they have few competing interests and “no longer see each other as rivals.” In a slide he used for his presentation, Iwashita said both “accept and manage the realities of the ‘quasi-alliance.'”

He said that Japan’s view of the Russia-China relationship differs from the United States in significant ways. Tokyo sees both countries as neighbors while Washington views Russia as an extension of Europe and China as a rising power in the Asia Pacific.

While China’s land borders with Russia and all its neighbors but India are settled and peaceful, Beijing sees itself as being “surrounded by many countries” on its coast, leading to maritime “border paranoia.” To counter that perceived threat, it has been reclaiming reefs in disputed waters of the South China Sea to install military installations.

The Chinese “want some greater say in their region,” Thomas Wright, of Brookings, said. Beijing believes “the environment changed with the financial crisis” of 2008 and it no longer need acquiesce to United States leadership or power, as it did during the Taiwan crisis of the 1990s.

Russia and China have different ways of asserting themselves in light of what both see as different circumstances.

Russia under President Vladimir Putin is “determined to take great risks to weaken” the European Union and the Western security alliance. China, while asserting its claims aggressively to the South China Sea, has “a lot of means at its disposal” to expand its influence — especially economically.

“Chinese strategy only works if there is no war,” he added as it “takes incremental steps to gradually remake” the world order in Beijing’s favor.