CORONADO, Calif. – As her dad stepped off the chartered airplane, 5-year-old Ashley Boemmel could barely contain her joy. But with her mother’s urging, Ashley dashed across the tarmac at North Island Naval Air Station’s air terminal and ran into her father’s arms.

“It’s great. I’ve looked forward to this moment for awhile,” said Senior Chief Information Systems Technician (SW) David Boemmel, clutching her as a gaggle of television cameras gathered around them shortly after the midday Friday arrival. The sight of North Island before the chartered plane landed “was surreal” but marked some relief as the historic hull swap was near the end.

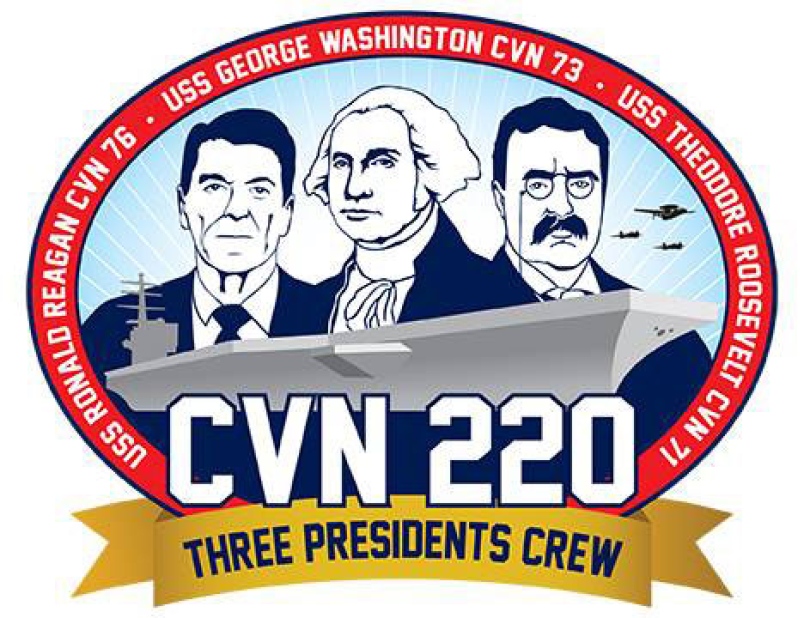

Boemmel was among the last groups of 1,200 sailors known as the “Three Presidents Crew,” or “220 Crew,” a nickname marking the sum of the three hull numbers (71-73-76) in the Navy’s historic hull swap of aircraft carriers.

The “220 Crew” are Ronald Reagan sailors who rode that carrier last year from San Diego to the Reagan’s new homeport in Yokosuka, Japan. They then swapped crews and cross-decked to USS George Washington (CVN-73) for a deployment to South America, stopping in San Diego and training in South America before continuing onto to Norfolk, where George Washington will undergo the lengthy mid-life refueling complex overhaul (RCOH). In Norfolk, they did the turnover with George Washington’s crew and, over recent weeks, have been returning to San Diego and taking over as the new crew for USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), which in November made San Diego its new homeport.

The final group of Theodore Roosevelt’s “220 Crew,” mostly senior sailors who have overseen the final aspects of the turnover aboard George Washington, is scheduled to arrive at North Island sometime Saturday.“Today is the last day of the swap,” said Mass Communications Specialist Senior Chief (SW/IDW/AW) Terry L. Feeney, a Roosevelt spokeswoman.

The triple swap enabled Boemmel’s wife Ristuko and daughter to remain in the San Diego area, their home for five years. “We knew what to expect,” he said of the “220” crew. “It would be very stressful.”

By swapping hulls rather than crews, the Navy estimates it’s saved $41 million in relocation costs for sailors making permanent-change-of-station moves. Most of the sailors and families got to remain in their homeport, although the carriers retained their crews in the respective reactor departments.

If the Navy’s plan was to reduce household moves and ease the strain for the families, the unexpected pain was felt across the decks and took its toll on sailors, especially those who did the triple swap

Boemmel described the experience as “very challenging, very rewarding. It hasn’t been done before in the Navy. It was exciting to be a part of that.”

“I’ve been told I have a few more gray hairs than before I left, and I’ve lost a little weight,” said Theodore Roosevelt’s Command Master Chief Spike Call, who waited outside the air terminal along with a handful of other relatives welcoming 150 sailors arriving in two flights from Norfolk.

“I’ve been told I have a few more gray hairs than before I left, and I’ve lost a little weight,” said Theodore Roosevelt’s Command Master Chief Spike Call, who waited outside the air terminal along with a handful of other relatives welcoming 150 sailors arriving in two flights from Norfolk.

Call credits professional leadership and teamwork at all levels with making it a smooth transition, despite the stress and tiring work. His message to the chiefs’ mess, he said, was this: “We’re going to make our money controlling anxiety.”

“So we need to continuously talk to our sailors about everything that is going on,” he said. “Tell them everything, right up front…, even at the earliest stages. Even if we don’t know if it’s going to happen or not, we’re thinking this is going to happen. You’ve got to tell them.”

Call had the unusual role of being the top senior enlisted for three aircraft carriers over a short period of time, riding the hull-swap tide as CMC first with Ronald Reagan, then George Washington and now with Theodore Roosevelt over a five-month period. During that time, he worked with three sets of commanding officers and executive officers, as well as some new faces in the chiefs’ mess.

“The challenge for me, quite frankly, was pretty big,” he said. “I had to learn three sets of COs and XOs, really quick. The relationship between a captain and his CMC, most of the time, is very close.”

Like others in the “220 Crew,” Call had to figure out quickly the differences between the three carriers, which ranged from berthing locations to combat systems. “Each ship has its own soul,” said Feeney. While the carriers’ media studios mostly were in similar spaces and decks, each ship’s CMC’s office was in a different place.

With short crew turnovers, the sailors had little get-to-know-you time. “It was exhausting, quite frankly,” Call said. “You have to make friends fast.” He added: “Sometimes it was difficult, but we are chiefs. We’re going to get through it.”

Call and the crew rode George Washington around the tip of South America. “We didn’t have any issues coming up around the horn,” he said, a testament to the crew “taking care of each other.”

Theodore Roosevelt’s materiel condition “is quite awesome,” Call said, even after a long eight-and-a-half-month deployment that ended with its Nov. 23 arrival in San Diego. “You could tell those sailors really took care of it well.”

The coming months will be busy for Theodore Roosevelt, which shifted from North Island’s Lima Pier to its permanent berth at Kilo Pier. As ship’s company settles in, sailors will prepare for an upcoming planned incremental availability starting in the spring, Feeney said.

“The next six months is when we are really going to gel as a crew,” Call said, “and then we’ll put all the hull stuff behind us. Then we can think fondly of it.”