LONDON — Five years ago the Royal Navy was reeling from the impact of the British government’s 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR), a financially-driven undertaking that resulted in the scrapping of the last two Invincible-class light aircraft carriers, the withdrawal from service of their Harrier jets, the sale of one amphibious-dock ship and the mothballing of another and severe cuts to the destroyer and frigate force.

Now the senior service is embarking on a fresh maritime renaissance that will see it deliver enhanced capabilities in partnership with its most enduring ally. That, at least, was the message delivered by the Royal Navy’s First Sea Lord Adm. George Zambellas and his American counterpart at a joint seminar in London on Wednesday.

“There are few areas where our strategic interests are more natural, or our global interests are more aligned, than at sea,” Zambellas told an audience at the Royal Institute of International Affairs — also known as Chatham House.

Zambellas said the 75-year-old partnership, which dates to the Battle of the Atlantic in World War II, is about to become “even closer and stronger” thanks to a combination of sustained investment in ships and equipment and on the “direct practical [and] spiritual support we’ve had from the US Navy.”

The introduction of a wealth of new assets—including aircraft carriers, attack and ballistic-missile submarines, destroyers, frigates and offshore patrol vessel—would ensure the Royal Navy is “more credible in the eyes of our most important partner than ever before,” he said.

In December 2014, Zambellas and the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert signed a Combined Sea Power agreement—a shared vision for naval cooperation for the coming 15 years.

The accord addresses five key areas:

- The close co-ordination of carrier strike operations, with the new Queen Elizabeth-class carriers (including F-35B strike fighters, helicopters and unmanned air systems) reinforcing the capability provided by the U.S. Navy.

- The integration of U.K. and U.S. ships in one another’s maritime task groups, a process that should become “intuitive.”

- Additional personnel exchanges, particularly in headquarters and niche roles where it is important to preserve perishable skills.

- Mutual investment in technologies that permit interoperability, including weapons, sensor systems, data processing and protocols, and autonomous vehicles.

- Force and capability planning “to ensure that together we maintain a balanced mix of capabilities and that our activities complement our mutual priorities.”

Zambellas said: “Together or individually we must be ready to project power and respond to crises around the world quickly, flexibly and credibly. For the next 15 years and more, we are designing and deploying naval forces to be more than interoperable. From the outset we aim to be integrated, working in unison, not in tandem.”

Greenert told the seminar: “We depend on the Royal Navy, very much so, from tactics, to operations to strategy. From world wars, through the Cold War to today, we have always been stalwart allies. Today we enjoy a closeness and an unconditional trust that is really unequalled anywhere around the world. From a schoolhouse, to an exercise, to a deployment, to a real world combat operation, Royal Navy members are embedded throughout our ranks.”

The CNO pointed out that already British pilots were the only foreigners permitted to fly Super Hornets on strike missions. “No other pilot can even sit in a Hornet, because they can’t get the clearance. Of all the allied training that we have, we can only trust the [RN-run] Perisher course . . . to qualify our nuclear submarine commanders.”

Greenert said the future belonged to “collaborative operations, integration, truly global force management and force development” and highlighted continuing cooperative technological work in mine warfare (particularly unmanned underwater systems), antisubmarine warfare (advanced sonar arrays) and in “unique high-tech asymmetric capabilities” such as the F-35, carriers and submarines.

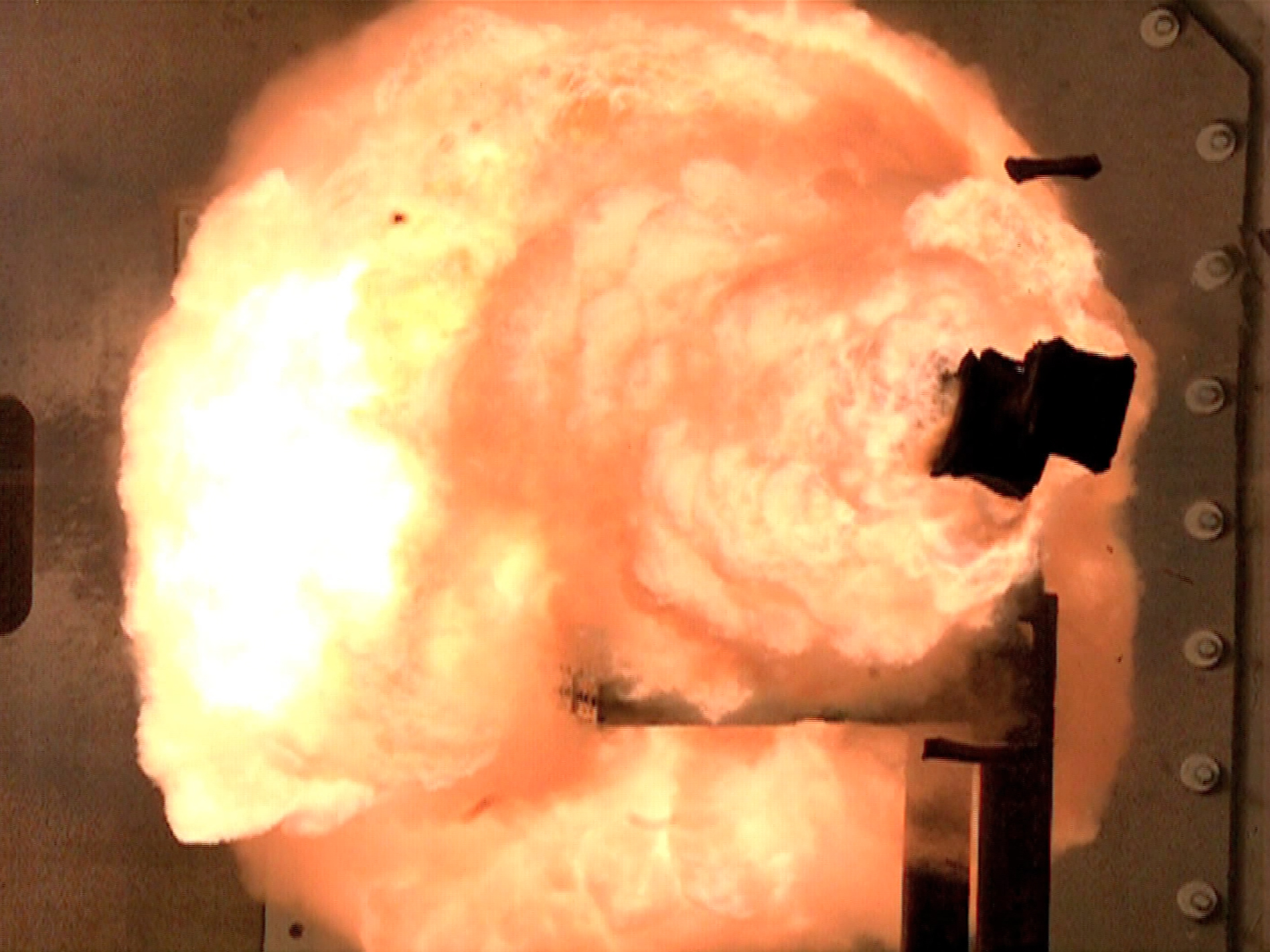

He also disclosed that British exchange officers were working on the U.S. electromagnetic railgun program.

“The value of the relationship by far is greater than the sum of our forces.” Greenert said. “It’s a very, very powerful symbol by the two leading democratic nations, and our forces represent freedom and liberty around the world. I hear it again and again from other potential partners: they say ‘We depend on you, we look to you and the U.K. to show us how can two nations come together for these very complicated operations of the future.’”

“Our cooperative SSBN program and our carrier programs are truly iconic and will bring us that true global force management.”

In a turbulant world, Greenert said, one thing would remain certain: “The U.K. will always be our commited ally, and the Royal Navy will be my vital partner and of those that come after me.”

The British government recently committed to spending 2 percent of GDP on defense, meeting the NATO guideline figure, and has a 10-year equipment program valued at $249 billion. The results of a second SDSR—with direct U.S. involvement in the process —will be published in 2016.

Citing collaborative deployments in the Baltic Sea and Persian Gulf, Britain’s Defense Secretary Michael Fallon told the Chatham House seminar that the relationship between the two navies “goes from strength to strength.”

Research agreements for submarines and other undersea systems would ensure “that our two countries maintain our technological edge in a world of weapons proliferation, of exponential technological advance and increased defense competition amongst emerging nations. We do this together as primary partners, indispensible to each other,” he said.