Exasperation over foreign perceptions of insecurity in Nigerian waters is all too common.

At a time when the International Maritime Bureau recorded “only” 18 attacks in Nigerian waters compared with 31 the year before and when a report by the U.K.-based maritime intelligence provider Dryad Maritime declared a “drop of 18 per cent of attacks in the Gulf of Guinea” the perception of the Gulf of Guinea as a high-risk area drove an infuriated Director General of the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) to accuse:

“foreign insurance companies otherwise known as Protection and Indemnity (P&I) clubs, of sabotaging Nigeria’s economy especially in the report of piracy activities in the sub-region.

Director General of NIMASA, Ziakede Patrick Akpobolokemi, said that P&I clubs deliberately raise the red flag on vessel operating in sub-Sahara African region in order to milk them of more insurance money, lamenting that a lot of losses are being incurred through the marine insurance sector,” read a report in the Nigerian Daily Independent.

Whatever one’s view may be on the state of maritime security in Nigeria, what is clear is that there are considerable commercial stakes tied to how maritime crime is reported and how stakeholders interpret and act on it.

Beyond issues of definition of what piracy really is (and how it differs from other maritime crime), the Gulf of Guinea presents a classic example of how incident numbers shape perception of maritime security risks. Yet these numbers and trends differ depending on who counts and reports them and, more crucially, there is often a story behind the number that is not always told. This article will examine how different organizations quantify armed robbery and piracy risks in the Gulf of Guinea, how it shapes their analysis, and why there appear to be different interpretations of the security situation in the industry.

The Baseline: The International Maritime Bureau (IMB)

The press—both popular and specialized—rely to a large extent on the figures provided by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and the IMB. For many readers and stakeholders in the industry the quarterly and annual IMB reports map the “fever curve” of piracy. The IMB has its own definition of piracy, which is:

The press—both popular and specialized—rely to a large extent on the figures provided by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and the IMB. For many readers and stakeholders in the industry the quarterly and annual IMB reports map the “fever curve” of piracy. The IMB has its own definition of piracy, which is:

“The IMB Piracy Reporting Centre (IMB PRC) follows the definition of Piracy as laid down in Article 101 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and Armed Robbery as laid down in Resolution A.1025 (26) adopted on 2 December 2009 at the 26th Assembly Session of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).”

In principle, this definition covers maritime criminal acts both on the high seas and inside territorial waters as long as they are not politically motivated (i.e., terrorism, insurgency). The data is obtained through the Piracy Reporting Centre, to which masters, shipping companies, and flag states can report. For data capture the IMB relies on a comprehensive piracy reporting form that can be completed by any of the aforementioned parties. The data points in this form are the basis for the analysis in the quarterly and annual reports and have remained consistent since 1992. The IMB reports allow filtering and analysis for the following criteria:

- Location;

- Actual (successful) or attempted (failed) attack;

- Attack categories (boarded, fired upon, hijacked);

- Weapons used;

- Types of violence;

- Types of vessels attacked; and

- Nationalities of vessels attacked (flag states, operator/owner state).

The IMB reports are a practical tool for analysing the symptoms of attacks, i.e., who is at risk and where, but little else. And indeed, they do not aspire for more—the IMB’s purpose is precisely to draw attention to the symptoms of piracy and their impact on seafarers and vessels. The reporting is not designed to explain the criminal phenomena. Curiously, many academic works draw on the IMB’s figures for analysis purposes of the nature of piracy (or maritime crime), something for which those figure are singularly unsuitable. As the 2014 IMB reports acknowledges:

“There is considerable under reporting of incidents in the Gulf of Guinea. Bergen Risk Solutions have reported a little more than double these incidents for West Africa.”

Thus, while there is benefit in having a degree of “credibility” inherent in the IMB’s reporting, it also has significant drawbacks in that it tends to understate real maritime security problems, narrows the focus on “acts of piracy” and lacks an assessment on the impact on local shipping and maritime activities. This is particularly the case in the Gulf of Guinea, where both in terms of incident numbers, but also in terms of monetary turnover, much of the criminal activity unfolds in the coastal and inshore waters and mostly involves stakeholders that for various reasons do not, or cannot, report to the IMB.

At first glance it may not seem apparent how attacks on oil and gas infrastructure, small passenger boats and swamp-based platforms in the Niger Delta impact on international maritime commerce. However, not limited to the Niger Delta, the clues for interpreting and also very often for forecasting maritime crime in general and piracy in particular lie on land and are deeply interwoven with the local context. For example: criminals in the Niger Delta often steal boats and engines that they use for attacks against other vessels at a later point. In other instances, increased militancy in the Niger Delta usually turns the attacker focus to oil and gas targets, usually inshore or “close-offshore,” whereas a “pacified” situation in the Delta means that criminal potential is available for other activities farther offshore. Equally, there is a distinct difference in the type and amount of violence that Niger Delta attackers mete out on their victims, depending on whether they are locals or crews of internationally trading ships.

From Informational Monoculture to Confusion

Since the inception of the ISPS Code in 2004, and further accelerated through Somali piracy, “maritime security” has evolved into both a commercial activity outside the realm of law enforcement and a field of academic enquiry, ideally encompassing diverse issues such as piracy, cargo theft, various types of trafficking, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing as well as boundary disputes. In short: it is much more than just “piracy”, which often makes maritime security risks difficult to quantify—they are not countable. At the same time, industry and stakeholders demand “numbers” upon which they can base their (often quantitative) risk assessments. For better or worse, an increasing number of organisations now deliver those numbers.

Very often there are messages attached to the numbers—as was the case of the 2014 Dryad report cited above, which qualifies the drop in piracy numbers by saying that at the same time there was an increase in offshore kidnapping incidents in Nigerian waters – from 8 in 2013 to 14 in 2014. Considering that the IMB in 2014 only logged 18 incidents in total for Nigeria, of which only one was a kidnapping, it is understandable that stakeholders and agencies are receiving mixed signals.

The key to understanding how incidents are reported, especially outside the IMB and IMO, is the market for maritime security information. It is largely driven by commercial interests, hence the numbers serve to bolster commercial decisions. While useful, it requires some circumspection and knowledge how those figures were arrived at, especially if they are used by anyone else than the intended audience.

A Comparison of Incident Reporting and Analysis

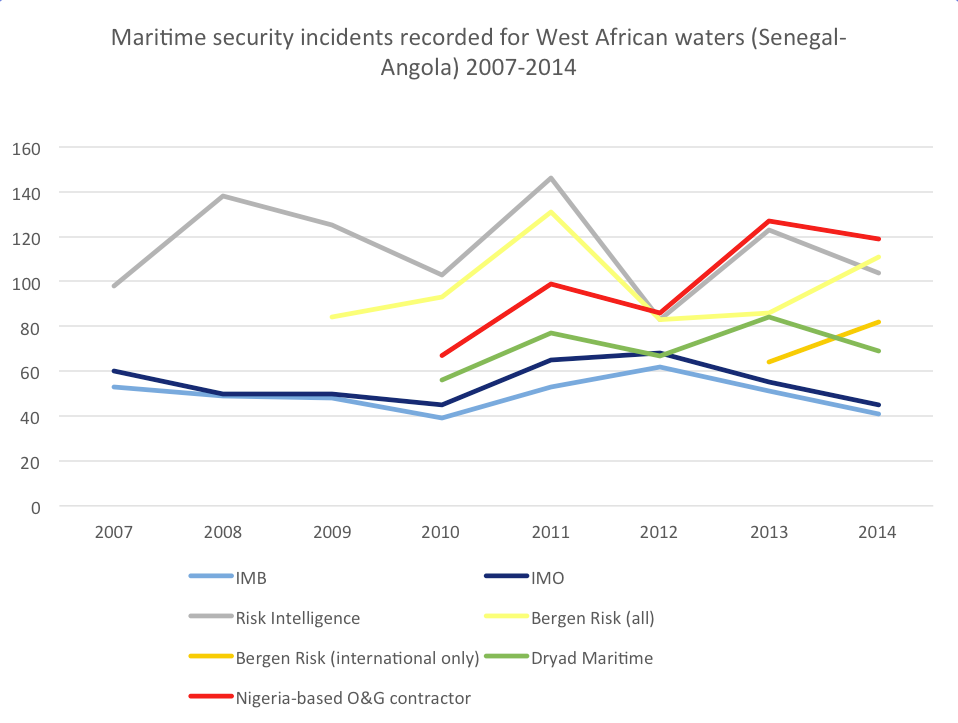

A comparison between three globally operating providers of maritime security information, the security department of an oil and gas contractor with a focus on operations in Nigeria and the IMO and IMB provides an idea of how both methodologies and target audiences shape absolute numbers and interpretations.

While IMB and International Maritime Organisation (IMO) rely on incidents being reported to them and, other than encouraging members to report, do not actively seek incident data or further verification, commercial entities are doing just that, but in different ways.

- Risk Intelligence, [the author is an employee of Risk Intelligence] a Denmark-based provider of security intelligence, uses a mixture of privileged and open sources and records. It processes and displays incident data in a maritime domain awareness tool and database called “MaRisk”. Because this system is designed to be used operationally, it captures all incidents that the analysts consider to be of relevance for users to make an informed assessment of a maritime security situation. This may include terrorist, insurgent and other criminal activity, which is not directly related to piracy. However, the incident count is based on “piracy-like” events. Local incidents are recorded, but for the sake of clarity, not all are displayed or counted, especially when they are impossible to verify.

- Dryad Maritime is a U.K.-based maritime operations company with a high-grade maritime intelligence capability. The company supports clients’ maritime domain awareness through a variety of products and services. Although Dryad’s open and privileged sources capture all reported waterborne crime incidents, their analysts only issue intelligence reports based on the incidents that are considered relevant to their commercial clients’ needs. As a result, the incident count is based on events that are likely to impact international commercial ship operators in transit to/from or operating in/near ports or offshore terminals. Local incidents, such as theft or kidnapping in riverine areas are recorded for internal use but do not normally result in reported incidents or feature in annual figures.

- Bergen Risk Solutions (BRS) of Norway uses data provided by “official” information providers such as the IMB, IMO, U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence and MTISC-GOG. In addition, BRS include information collected from credible media and other open sources, clients as well as a network in the maritime and security sectors in Gulf of Guinea. All information of incidents is assessed and cross-checked before being stored in the proprietary maritime security database—the “Blackbeard”. BRS maintains two sets of statistics: one including all recorded (verified and probable) incidents and another for such incidents that involve “international stakeholders only”, i.e., where attacks/incidents purely targeting local shipping have been omitted. International stakeholders means “owned/managed by, working for, or associated with” international companies or projects. The reason for doing so is for ease of verification and consistency of statistics over time.

- A Nigerian subsidiary of an international oil & gas contractor that specializes on the management of offshore oil and gas support vessels collects incident information through a robust local network. The data is designed to assist the company’s risk management, which is independent of that of the oil companies. The information is not typically published but circulated among the company’s clients, business partners, and principals, where accurate reporting is required to obtain the necessary security support during contracting phases. The company operates numerous vessels in Nigerian waters, along with other Gulf of Guinea countries the company’s main market. Incident counts therefore focus on Nigeria and other Gulf of Guinea countries.

When looking at the numbers, not only does it become clear that the piracy problem in Nigeria is not new, but that micro-trends, while generally perceived, are interpreted differently. Risk Intelligence’s database captured the heightened offshore militant activity during the MEND (Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta) insurgency between 2006 and 2009 whereas IMB and IMO numbers were showing a decline in “piracy.”

Then as now, Risk intelligence’s figures come with a caveat attached that militancy tends to focus closer to the Niger Delta and actually takes some pressure of non-oil & gas related shipping—seemingly corroborating the IMB and IMO view. In truth, however, IMO and IMB numbers were obscuring the truth—suggesting an “improvement” of the situation when in fact it was only a temporary change of criminal focus.

Most in the industry agreed on the increase of pirate activity in 2011—largely owed to tanker hijackings, many of them taking place off Benin and Togo, though perpetrated by Nigerian criminals. Curiously, IMB and IMO reported only a modest increase in 2011 and a “spike” in 2012 when there was a relative lull in Gulf of Guinea piracy.

In 2014, IMB and IMO reported a decline in piracy for 2013 (although the IMB report does point out the notable increase in kidnappings), when in fact the first half of 2013 witnessed an extraordinary series of kidnappings up to 150nm from the Niger Delta coastline, which primarily affected international shipping in transit. This phenomenon subsided in the second half of 2013 to be replaced by a spate of kidnappings closer to the Niger Delta. From a risk management point of view, neither IMO/IMB’s nor any of the other annualised figures or interpretations do justice to this development, which should have had a profound impact on how risk was perceived by operators of different types of vessels in the Gulf of Guinea.

Finally, 2014 showed a decrease for most observers, except for Bergen Risk, but based on an “inclusive” count that reduction was negligible—well within the margin of reporting inaccuracy—and generally (especially with regards to kidnappings and hijackings) remained on an unacceptably high level, indicating a continued lack of successful enforcement. Again, the devil is in the detail: while Dryad pointed out the higher number of offshore kidnapping incidents, a Nigerian-based oil & gas contractor reported that fewer individuals had been kidnapped and that fewer foreigners (20 compared with 51 in 2013) had been abducted. This figure also holds for Risk Intelligence, who recorded only an incremental increase from 29 to 32 maritime kidnapping incidents in 2014, yet inshore and local maritime kidnappings were included in these figures.

This brief overview shows that depending on the source of information, the type of analysis, the depth of detail and the reporting requirements of the client, the interpretation of maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea can differ significantly—with a potentially profound impact on the industry’s risk management posture and on stakeholders’ and policymakers’ reaction to the situation.

The Limits of Counting Incidents

Numbers—and incident numbers—will remain with us for the foreseeable future. They provide quick and accessible information for those who, for various reasons, do not or cannot involve themselves in the often arcane qualitative analysis of criminal phenomena at sea. In principle, there is nothing wrong with quantification, when it is done correctly and consistently. And this is perhaps the greatest pitfall that these numbers present when used out of their context. If the wrong metrics are chosen for analysis, flawed policies and countermeasures are bound to follow.

A classic example was the use of the enemy “body count” as a measure of success in the war against the Vietcong by the U.S. Army. The result of this flawed metric was that by the late 1960s the United States and its South Vietnamese allies were surprised that they were actually losing the war at a point where they thought, judging by the number of enemies killed, that they were doing rather well, according to Scott S Gartner’s book Strategic Assessments in War. Today, almost five decades and several hard-fought counterinsurgency campaigns later, we know that more reliable metrics include the density of counterinsurgency forces, force/population ratios, development activities etc., or as a U.S. Army manual puts it: “[r]aw counts of something is usually not as important as how many out of a possible total and how important each one is.” ( U.S. Army’s May 2014 update to its counter insurgency field manual.)

Similarly, the lack of standardized criteria for incident reporting today are partly responsible for the lack of policies, or for the inadequacy of policies, to counter maritime insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea. As pointed out above, only the IMB uses standardized figures, but they are geared toward industry rather than policymakers and their narrow focus, lack of context and low numbers do not provide an adequate basis for statistical analysis or quantitative measurement.

The current system of counting and reporting incidents in the Gulf of Guinea is imperfect and often distorts reality to the point where resources are misallocated and policies ineffective. Confusion reigns over what, if anything, is effective in reducing maritime insecurity in the region. This problem is not new, but in addition to more comprehensive and systematic reporting of all types of incidents there is also a need to better understand the qualitative facets behind the numbers, not least to be able to identify ways how to better quantify the data.

In developing metrics and incident criteria we need to ask ourselves: to what question do the numbers that we report and consume provide an answer? Acts of piracy and armed robbery are only one facet of the spectrum of maritime insecurity; boundaries between various crimes are often blurred. A good example are product tanker hijackings in the Gulf of Guinea: while they were difficult to predict prior to 2010 their modus operandi evolved almost naturally from related activities by criminal gangs, such as illegal bunkering or fuel subsidy scams in Nigeria, often using identical infrastructure and personnel. The situation may yet revert to the original state and re-emerge in a different form later, but sheer numbers obscure the shifting ground as one sector of shipping gets a temporary reprieve (tankers) another sector (offshore oil and gas) becomes the focus of new, yet related, criminal activity.

Conclusion

The need to obtain a quantitatively and qualitatively better picture of maritime security threats in the Gulf of Guinea (and elsewhere) has only recently been identified as both African and external stakeholders have engaged in a more systematic way to approach maritime security around the African continent.

If African, European and U.S. strategies for the Gulf of Guinea are to succeed, they will require a deeper understanding of maritime security problems than can be derived by inductive analysis based on the often flawed and incomplete observations and recorded incidents that exist. Unsurprisingly, both the European Union and African Union documents set forth the need for a more comprehensive understanding as their first objectives, suggesting that what is available is not nearly enough to develop appropriate policies. *

A meaningful solution is likely to involve stakeholders across the board, including regional and foreign governments, private security companies, shipping companies and academia. It will also involve a fundamental rethinking of how we categorize, report and analyse incident data in order to arrive at a common basis for understanding the problem.

In summary, while there is no “right” or “wrong,” depending on the basis on which incident quantifications are carried out, a case can be made that deeper understanding of the threat situation and drivers usually engenders a more fine-grained (though not necessarily more) reporting. It is usually commercially more valuable than “sketchy” figures, but conversely often less readily “accessible” for a general public due to the many reservations and qualifications that are attached to those figures. Simply put: numbers alone do not provide an understanding of a maritime security situation. The intelligence analysis behind them does.

*African Union, Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (2050 AIM Strategy), AU Version 1.0., 2012), 11 and Council of the European Union, EU Strategy on the Gulf of Guinea (Brussels: 17 March 2014), 9 and European Council, Annex to Council conclusions on the Gulf of Guinea Action Plan 2015-2020 (Brussels: 16 March 2015), 14, although the action plan already pre-supposes certain threats and trends based on flawed reporting described in this article. The United States Counter Piracy and Maritime Security Action Plan (June 2014) purports to provide a brief overview of the threat, but implicitly relies on incomplete data provided by the IMB for some of its analysis (e.g. Annex B “Framework for Combating Piracy and Enhancing Maritime Security in the Gulf of Guinea”, p.3) and also views piracy in the Gulf of Guinea in isolation of most other forms of crime (except oil-related crime) and largely as a threat to energy security.