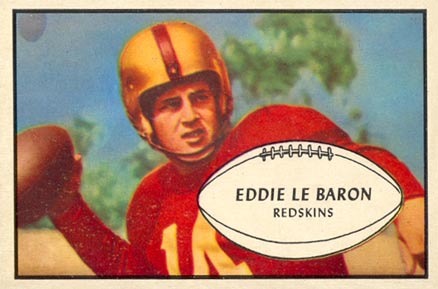

The following is a column by former Marine and NFL player Eddie LeBaron that ran in the October, 2009 issue of Proceedingswith the original title Two Dreams Came True. LeBaron — the first quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys — died on Wednesday in Stockton, Calif. He was 85.

As a high school kid in Oakdale, California, during the 1940s, I never had any doubt about what I’d be doing when I grew up. I wanted to become an all-American football player and a combat Marine. As it turned out, I did both—and the two have complemented each other throughout my career.

World War II had just broken out when I began my teen years, and my heroes were the great college football players of the day and the Marines who were fighting at places like Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima. I’d entered high school at age 12, and quickly became the starting tailback. But I was too young to join the Marines when I graduated, so I went to the College of the Pacific, where I ultimately made all-American. At 18, I joined the Marine Corps Reserve in nearby Stockton.

I was at a practice session for the College All-Star Game when the Reserves were called up after the outbreak of the Korean conflict. I was commissioned directly and ordered to Quantico for Basic School; I arrived a bit late after being permitted to play in the game. But I quickly learned there were a lot of similarities between the way the Marine Corps trained its people and the way football coaches ran their training camps.

At Quantico, they teach you the “school solution,” which provides a basis for handling most of the challenges you’d have to deal with in combat. But they also teach you how to think on your own to solve problems that arise. In football, they teach quarterbacks the same sort of thing—how to find a workable alternative when the “school solution” isn’t likely to work. In both cases, you have only a split second to decide.

But Basic School also taught us a different kind of discipline from the one we used on the football field, and it was just as valuable: when you’re given an order, you have to follow that order unhesitatingly. But when you’re the one giving the order, you have to make sure that it’s a good order before you give it—one that is based on a well-made decision, not on a slapdash judgment.

This was especially true in combat, where your troops had to have confidence that you were not needlessly putting them in jeopardy. But the lessons also carried over to my postwar career as a National Football League quarterback and, even later, to my days as a lawyer. No matter what you do, you have to be prepared for anything—so you can make a good decision when one is needed.

I finished Basic School in March of 1951, at age 21, and I left for Korea the next month. Thanks to football, I wasn’t as well-prepared as the others in my class: because of the All-Star Game, I’d arrived too late to practice firing my weapon—possibly the only Marine in history who was sent into combat without undergoing target practice. But I’d learned how to take all my weapons apart and put them together again, and I’d gone hunting a lot as a kid, so that kind of made up for some of the lapse.

A week after I arrived in Inchon, I got orders to go to the 7th Marine Division, which was pushing north to stop a Chinese drive from the Yalu River, and I quickly became a platoon leader, and later the senior platoon commander. We patrolled deep into enemy territory, breaking the communists’ defensive lines over and over again. Wounded twice, I received a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. One of the guys in our unit earned the Medal of Honor.

That fall, the peace talks began, and were held on and off for several months. While the two sides negotiated, we watched the enemy build strong defenses on the mountains ahead of us. The talks would break down, and we would attack the lines that they had fortified during the most recent truce-period. In the final battle of my tour, in a deep circular valley known as the Punch Bowl, we took heavy casualties. Eventually, we broke through, and the talks finally turned earnest.

In December 1951 I was sent back to Quantico to teach tactics at the Basic School. I left active duty nine months later, became a civilian again—and immediately joined the Washington Redskins. Trudging up and down the hills of Korea may not have been on the list of prescribed exercises for the National Football League, but it apparently kept me in good enough shape. I was voted NFL Rookie of the Year and went on to play 12 seasons of pro football.

In the late 1950s, I went to law school during off-season periods and passed the California bar exam. But before I could set up practice, the newly franchised Dallas Cowboys called to ask whether I’d like to play for the fledgling team, and I said yes. I was the team’s first quarterback, playing with Dallas from 1960 to 1962. Later I began a series of new careers-first as a sports announcer, then as an executive for the Atlanta Falcons and later as a lawyer.

I know it’s a cliche, but there’s no question in my mind that being a Marine—and having been in combat—did a lot to prepare me for success in the civilian world. As a Marine, you learn to give clear, concise orders, look after your people, and build a strong esprit de corps within your unit. If you can do this in any other organization or company, you’re bound to succeed there as well.

As a Marine, you learn to master a “school solution” for a wide array of problems. But you need to be ready to fashion a credible alternative when that doesn’t work. And you have to be physically and mentally ready to make decisions quickly and correctly. You need to foster the kind of spirit you find in the Marine Corps, where you feel proud to be a Marine and never want to let the Corps down.

My friends often notice with some amazement that so many of the country’s most successful people started out as Marines. To me, that isn’t a surprise at all. They all got the kind of training that lasts people a lifetime.

Answering the Call is a monthly series of short articles by prominent men and women discussing the impact of their time in the military on their later achievements.