The following is a remembrance of World War II Medal of Honor recipient Marine 1st Lt. Jack Lummus. The piece appeared in Naval History in 1995 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima with the original title, “To Love a Lost Hero.” Before the war, Lummus had played in the National Football League for the New York Giants and had played college ball at Baylor.

The contrast was striking. During the first few days after U.S. Marines landed on Iwo Jima in February 1945, First Lieutenant Jack Lummus was literally running messages between the Fifth Division’s 27th Regiment commander and Second Battalion Headquarters. Mean-while, I was walking the few blocks I traveled every day to work, worrying about my sweetheart’s safety out there in the Pacific. While Jack Lummus’s face grayed from Iwo’s volcanic ash, mine reddened in the Southern California sun. Then on 8 March 1945, while I was safely in my bed in Glendale, dreaming of “happily ever after” Jack lay on a hospital tent cot, think-ing his final thoughts, breathing his last prayers, unaware he would be called a hero.

A couple weeks later, Jack’s friend, Jim Tuttle, showed up on my doorstep with two other Marine officers. Tutt’s appearance struck me as odd. Was he trying to move in on Jack’s girl? I wondered. Jack’s V-mail, dated 25 February, had arrived that day. “I’m okay,” Jack assured me. I was so young, only 20. And I was so ecstatic to see a familiar face I could associate with Jack that Tutt did not have the heart to explain why he came.

Then, on the day President Franklin D. Roosevelt died, I dug a pile of letters out of my mailbox—letters I had written Jack that never reached him. I learned the hard way what Tutt and the other two should have told me. Each envelope bore the stamped declaration: “Undeliverable. Killed in Action.”

The message still broods in the back of my mind 50 years after that wretched day—a bluish-purple symbol of a loss that colored the rest of my life.

I had known Jack as a Marine who wore swimming trunks on the beach at San Clemente, as a suitor who looked so hand-some, stood so tall in his green wool uniform when he met my mother. I knew he grew up in Ennis, Texas, was one-quarter Chickasaw, and that a drunk had killed his father, a policeman. I did not know what he had eaten as a kid to help him grow so strong, nor whether he broke his nose in a schoolyard fight.

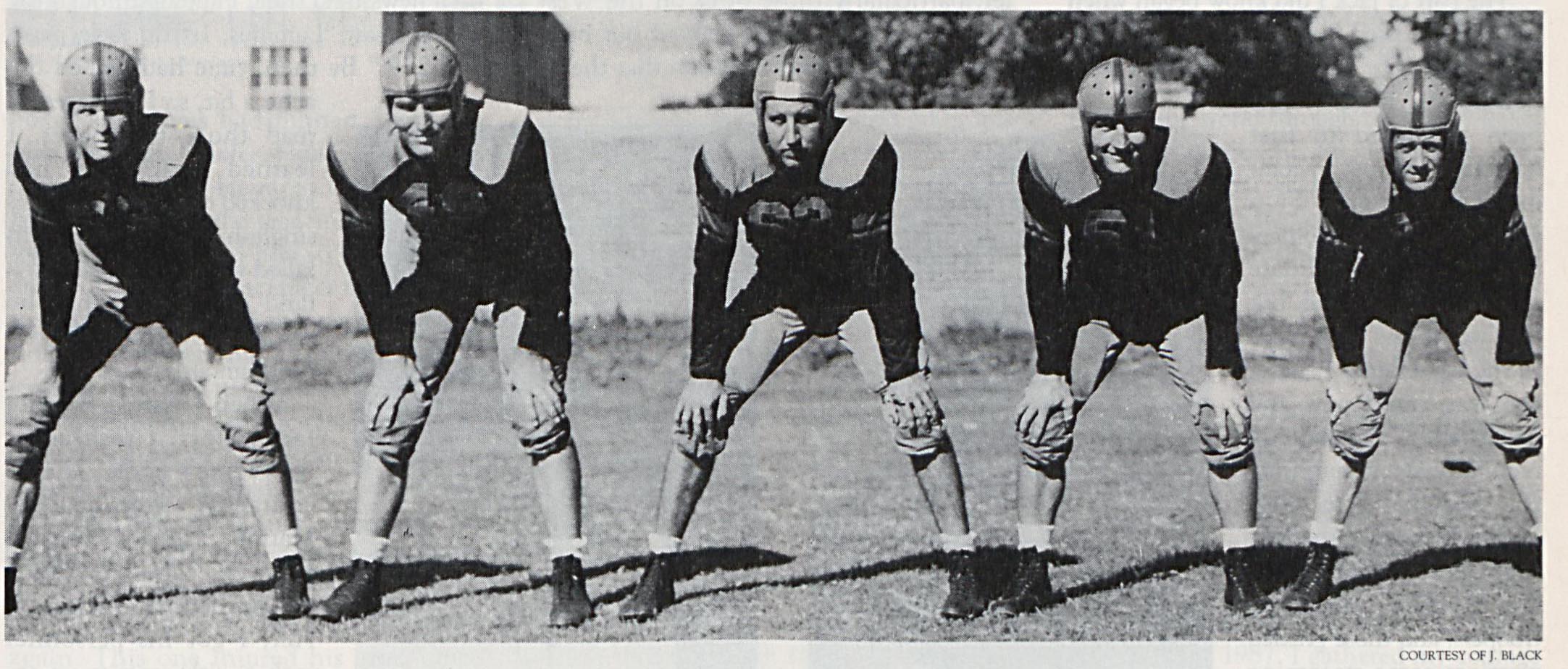

I had heard him reminisce about foot-ball games he had played with the Baylor Bears and the New York Giants. I did not know that sportswriters had twice nominated him All-American or that one of those times he had received enough votes to make honorable mention. Nor did I know he was such a natural at centerfield that one sportswriter dubbed him the best baseball “hawk” in Texas.

Seldom did we talk about weighty matters, such as whether he intended to go back into professional football after the war. We did what most other couples did during World War II: we danced and drank and loved. We had fun!

Jack talked about his folks, about his sister Hadji Sue, although he didn’t mention her married name. He offered to take me home once, but the trip fell through. Consequently, when he died, I never went to the family. Instead, I ran away.

I ran from places we had been together, ran from raw memories. I even ran out of the movie, “Sands of Iwo Jima.” I ran for several years, not trying to forget him, but rather trying to escape a hurt that stuck like glue. For decades, much about Jack remained a mystery to me. I knew he had died on Iwo Jima, but I knew none of the details. I did not even know where I could place a rose on his grave.

The part of Jack I did know began when our paths crossed two weeks before Christ-mas 1943. He was stationed at Camp Pendleton; he had just been promoted to first lieutenant and put in command of Company F—a heady dictate for an officer out of officer candidate school less than a year. But Jack was in the right place at the right time. Pendleton was brand new and understaffed. Thousands of recruits were enroute from the nation’s two boot camps. Moreover, the Marine Corps had disbanded the Raiders and Para-troopers, and those grizzled warriors came streaming into Pendleton from the opposite direction. Officers were at a premium, especially men with leadership qualities who could mold green troops and seasoned veterans into cohesive fighting units. Jack was the right man for the job.

But was he the right man for me? I remember getting a crick in my neck from looking up at him. I stood about 5 feet 7, tall for a 1943 girl—and “girl” is the right word, for I was a naive 19. I had just moved to California from my small Nebraska hometown. The Swedish boys I dated back home had pale skin, blue eyes, fine features. Before me that Friday night stood a 6-foot 4, raw-boned, bronzed young man with high cheekbones, a craggy, angular jaw, and ruddy hair. For a few minutes, I thought he was homely. Then he smiled his full, sweet smile, and my heart was lost forever.

By New Year’s Eve, we began to discuss marriage. My mother discouraged us. Jack would go overseas soon. If he came back, she ventured, he would likely be wounded, maybe even permanently disabled—or worse. She doubted I was mature enough to cope with that, and she asked Jack to wait until the war ended. Much to my disgruntlement, he respected her wishes.

In August 1944, the Fifth Division shipped out of San Diego. All I had to hold onto was Jack’s vague “plan” for us, a couple of snapshots from Hawaii, and a growing pile of letters.

Months later, news hit the papers that the Fifth was among three divisions fighting for Iwo. When the flag went up on Mount Suribachi, Americans breathed easier, particularly those of us on the West Coast. We went blithely about our business, under the misconception that the island was all but secured. But the battle continued for another month.

Then my complacent bubble burst. I can still see myself, sitting on the floor of the tiny rented house, those envelopes with their shocking stamp and unread contents scattered about me. One of my roommates dialed information and got a number in Ennis, Texas. A woman answered. Her husband had the same surname but was not related to Jack. He was, however, keeping a scrapbook of clippings about the town’s servicemen. She read us a brief item, a story of few details. Jack had been killed on Iwo Jima.

In my blind hurt, I vowed never again to set foot on the streets of Hollywood or Los Angeles, where Jack and I had walked together. Nor, God for bid, San Clemente.

I went to Phoenix and worked at radio station KPHO, which had dark announcers’ booths where a forlorn girl could cry in solitude.

Mother had been right. I did not cope well at all. I drank too much and developed a brittle laugh. VJ Day brought little comfort. Why, I protested unreasonably, had they not dropped the bomb five months sooner?

Finally, I moved back to Omaha and the stability of family. A couple years later, I married another Marine and bore him a whom I wound up raising alone.

Then, a quarter-century later, I spotted Richard F. Newcomb’s paperback, Iwo Jima, on a newsstand shelf. Flipping through the index, I saw “Lummus, 1st Lt. Jack, pages 218-219.” By then, time had healed the ache a bit, so I managed to read those two pages. I learned that Jack had knocked out three pillboxes single-handed, that he was killed when he stepped on a land mine, and that he earned the Medal of Honor posthumously.

When I started to write Jack’s story, I read all of Newcomb’s book. Then I contacted Headquarters Marine Corps and obtained Jack’s official records. Using the Freedom of Information Act, I got his personnel jacket with eyewitness accounts of the headlong acts that earned him the Medal.

As word got around about my quest, I heard from men who had known Jack—Marines, Baylor alumni, even a former pitcher with the Negro League, who played sandlot ball with Jack in the 1920s.

My Buick Skylark clocked hundreds of miles, as I attended Iwo Jima reunions, interviewing officers and noncoms who remembered him. I met aging men who had tried to tackle him during touch football games at Pendleton and Camp Tarawa. I heard from men who sat in bleachers at Mainside when Jack played centerfield with the top-notch Devildogs or at Camp Tarawa when he helped the 27th Regiment’s baseball team win the Fifth Division tournament.

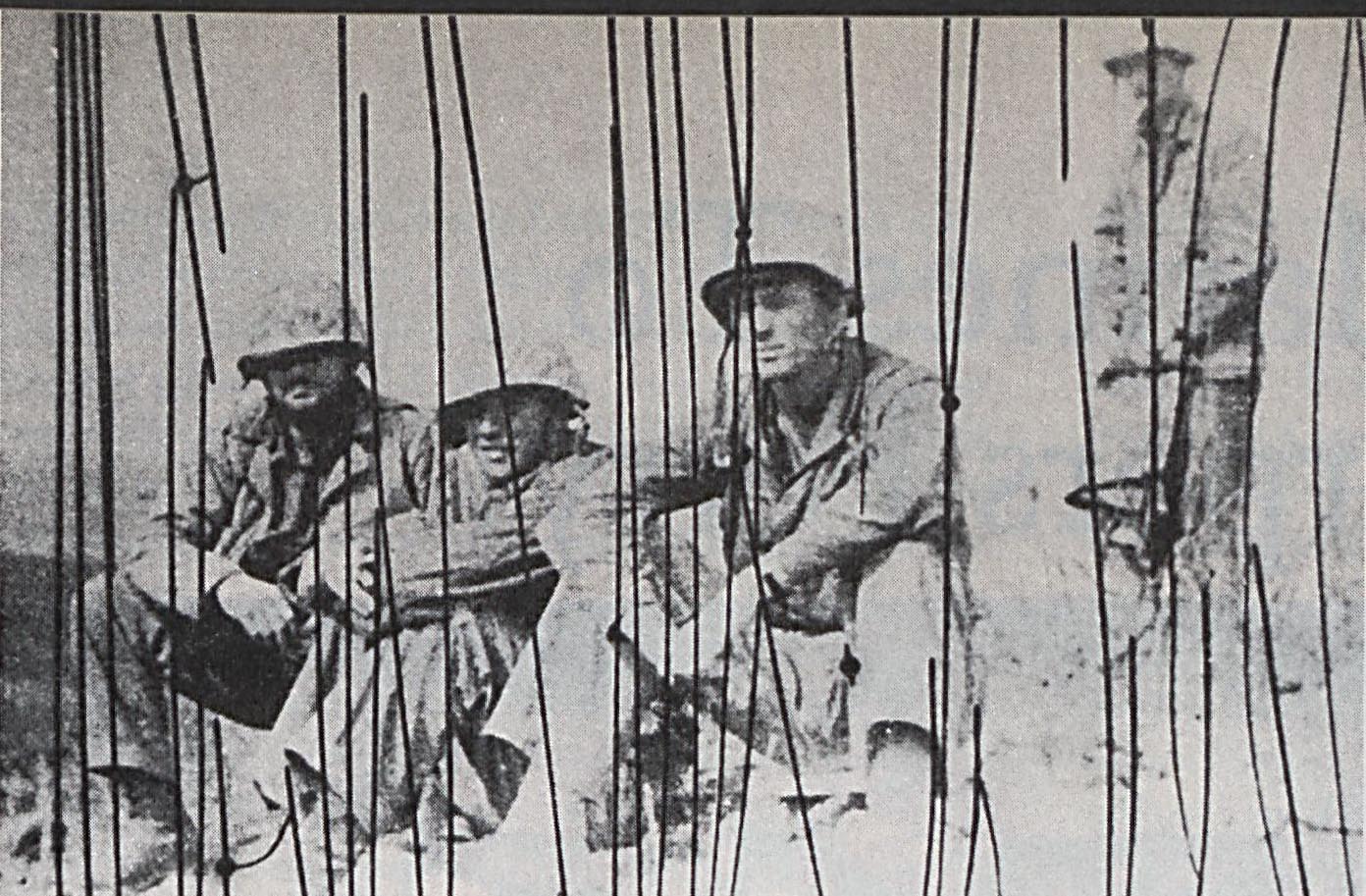

My file thickened. I learned that once phone lines stretched across Iwo, Jack stopped running messages and helped coordinate the Navy’s artillery fire. Then on 6 March 1945, he went to the front to lead Easy Company’s beleaguered third platoon through a strategic gorge — beleaguered because for 36 hours enemy snipers in pillboxes and caves had pinned down the Marines in shell holes. Finally, Jack could bear it no longer. He raced into no-man’s land, sprinting in the graceful, gazelle-likstyle that had scored him so many touchdowns.

Under constant sniper fire, he raced to the first pillbox and threw a grenade inside. He started back, but an enemy grenade exploded nearby, and the concussion knocked him flat. He scrambled to his feet, shook himself, and ran to his men. “Come on,” he ordered, “let’s get through the gorge.” Japanese in a second bunker opened fire. Jack started for that pillbox, but another grenade glanced off his shoulder and discharged, knocking him down again. This one injured his arm. Once more, he scrambled to his feet.

As he had during so many football games, Jack ignored the pain. He ran to the second pillbox and silenced the snipers inside. When the cloud of smoke cleared, the men saw Jack out front, waving his carbine, yelling, “Let’s go, let’s go.” By then, the men, as charged as Jack, jumped out to join him. Then a third pillbox opened up with a devastating barrage. Everyone scurried for cover—everyone, that is, except Jack. He rushed the emplacement and killed the enemy inside.

Then Jack led his men on a sortie against the Japanese snipers who were fir- ing on them from foxholes and spider traps, caves and shell holes. One of Jack’s machine gunners passed on a warning about Japanese land mines littering the area. A few seconds later, the Marines heard an enormous explosion. Their lieutenant had stepped on a land mine.

Out of the smoke, Jack appeared, struggling to stand—a vain struggle, for the blast had blown most of the flesh from both legs and nearly torn off one foot. “Keep going, keep going,” he yelled.

When the men of Easy Company’s third platoon saw Jack Lummus carried away on a poncho, they did precisely what he ordered them to do. They charged 300 yards through the gorge, blasting and burning more than 100 Japanese from their holes.

Easy and Fox companies followed, pouring through the gap to a ledge 800 yards forward—one of the entire operation.

Marine Corps historical records attribute that angry surge, that American banzai, for the fatal wounding “of a tremendously popular platoon leader, 1st Lt. Jack Lummus.”

Those angry Marines held that ledge for three days, until the remaining Japanese in that pocket surrendered.

“Thanks,” Jack replied, “but you’ll need it worse than I do. I’m headed State-side.” The reality of his situation hit him then, and he said, “Well, it looks like Giants have lost a damn good end.” He repeated that phrase over and over—an indication of the shock that not even 18 pints of blood transfusion would assuage. Jack’s willful determination—the spirit that sped him across the nation’s goal lines—kept him alive for several hours.

Doctors agreed later that Jack might have survived the butchery done to his legs, but not even that determination, nor his Atlantean physique, nor the palm-sized prayer book in his pocket could triumph over such devastating internal injuries.

Later that afternoon, Jack asked the pharmacist for a cup of coffee, took a sip, and let his head sink back down. He closed his eyes.

When I first read details of Jack’s death I was furious with him. Why did he take such chances? Why had he not been more careful? Why go after such a deadly goal?

For years I could not talk about Jack without my throat tightening up. I seethed with anger, for I had found what few of us ever find—that one special person—and I had lost him. What made Jack so special was his honesty, his “I cain’t he’p it, May-ry, I just love you;” the kick he got out of teasing me unmercifully; the way he looked right at the world through those gray-green eyes.

As I probed his life, it became clear the qualities that made him unforgettable were the very characteristics that propelled him into that horrible battle. His ethics, his stringent moral code, ended his life: fight to the finish, win at all cost, never admit defeat. He would not, he could not, quit.

I hated him for that. Finally, though, I accepted that Jack did what he must. He and the 6,820 other Marines, Sailors, and Seabees who died on Iwo Jima helped send home thousands of other Marines and rescued 25,000 aviators, whose Superfortresses made emergency landings on Iwo’s airstrips.

Finally, in 1987, I gathered my courage and realized my perennial wish. I drove to Texas, where Jack’s sisters opened their arms and welcomed me into their hearts.

I was a year late to attend the christening of the MVP First Lieutenant Jack Lummus, flagship of Maritime Prepositioning Ships Squadron Three. But of greater importance to me was the sunny August morning I carried a single red rose down a rock road through Ennis’s Myrtle Cemetery.

There I sat beside a flat tombstone and a replica of the Medal of Honor. A huge old elm shaded the family plot, and I pondered the questions of eternity and life hereafter. I do not know the answers. I do know that always feel Jack’s spirit there. And I know I have found him.

At last.