The following is a first person account of the events over the Gulf of Tonkin on Aug. 4, 1964. Another view of the Gulf of Tonkin incident can be found in the August, 2010 issue of Proceedings.

At approximately 0355 on the morning of Aug. 4, 1964 in the South China Sea, the aircraft carrier USS Constellation (CVA-64), was steaming toward the Gulf of Tonkin at as high a speed as she could without losing her accompanying destroyers. Despite an attack by North Vietnamese PT boats two days earlier, the U.S. government had decided to send the destroyers USS Maddox (DD-731) and Turner Joy (DD-951), on a route similar to the one where that attack had occurred.

The carrier USS Ticonderoga was already operating in the area and Constellation, though still about 200 miles away, was rapidly moving into position to provide support.

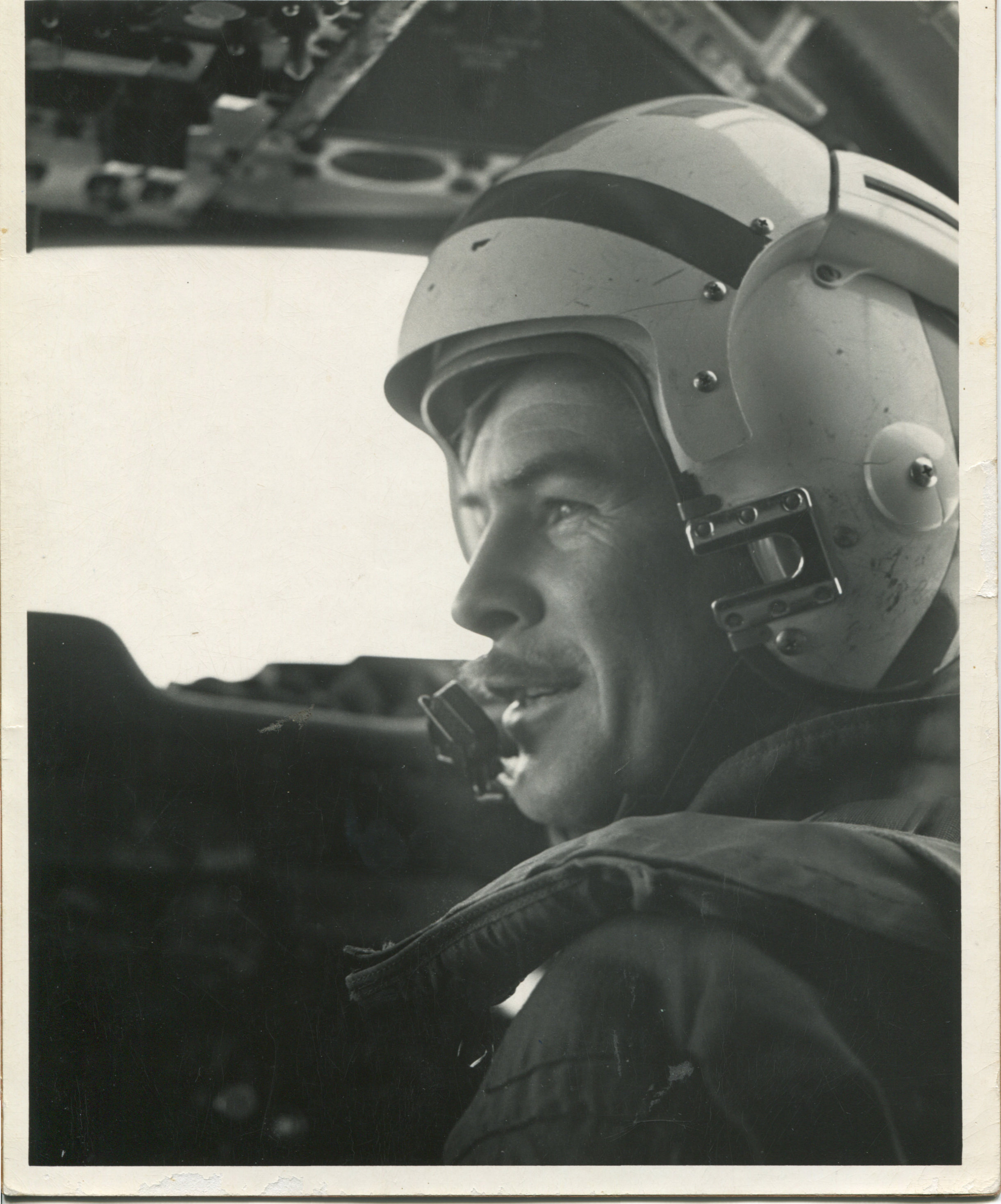

For four hours now, since midnight, my crew of four (including our radar intercept officer controller, Lt. (j.g.) Al Drum) had been on the catapult, strapped into our respective seats in the E-1B, awaiting the order to launch. There were about 30 knots of wind whistling over the open overhead escape hatch. The sky was black as ink.

It was my second cruise to Vietnam. I was 23 years old, a lieutenant (j.g.), and plane commander of the radar E-1B aircraft, affectionately known as the “Willie Fudd.” We were assigned to the Constellation as a part of the VAW-11 four-plane detachment, based at NAS, North Island, San Diego.

The E-1B was not one of the Constellation’s sleek jets, like the F-4 Phantom or the A-4 Skyhawk.

It was propeller-driven, and with its big mushroom-shaped radar dome sitting right on top, we weren’t going to win any beauty pageants. But we did have a job to do. Because of the earth’s curvature, the Constellation’s radar horizon could not detect low-flying aircraft much farther out than about 30 miles. Our role was to extend the range of the ship’s radar, and to intercept unidentified aircraft operating beneath her radar horizon.

The day before, the flight crews had been assembled and briefed on the upcoming operation.

The Mission

At midnight, the carrier went to flight quarters and to Condition One Cap, which required that the aircraft be manned and spotted on their respective catapult—100 percent combat ready and prepared for an immediate launch. I was assigned to the first four-hour watch, starting at midnight, and was spotted on the number two catapult. F-4 Phantoms were manned and on standby for launch along with the A-1Hs and the A-4s.

We were advised that we would be heading into an area saturated with severe weather of high seas and high winds with the possibility of thunderstorms. I knew the weather would be a factor, not only in flying the aircraft, but also in completing our orders, which were to locate the destroyers, which might already be under attack, and to provide positive control of the jet fighters that would be supporting the destroyers. If we could sight any North Vietnamese PT boats, that would be icing on the cake.

The main purpose for the E-1B was its radar. The radar of a fellow E-1B pilot had been able to pick up a five-gallon tin of cooking oil, for example. But radar in severe weather and high seas was a different matter. The sea “return” (the high waves) could saturate the radarscope by capturing the radar’s energy and reflecting it back as potential targets. That resulted in our getting “ghost” signals on our radar, and could make it impossible to definitively “paint” anything, even something very large — such as a destroyer — let alone a PT boat.

There was a way to minimize some sea-return, but in this weather, it would be a risky maneuver, requiring taking the plane down extremely close to the water—100 feet—and then tilting the radar antenna so it could look up, over the tops of the waves. It would be too hazardous to try on a night with near-zero visibility and turbulent water.

Besides, this maneuver created another problem—that of not being able to detect small vessels such as PT boats behind the sea return on the scope.

After four hours of sitting, strapped into our seats, waiting, we finally decided the order to launch was not coming. The next crew to take over the E-B would be in the ship’s island by now, ready to walk out to the aircraft as we left it. Our engines were shut down and quiet.

‘Launch the Fudd’

I shrugged myself out of my parachute harness and unhooked the leg straps, then unstrapped the buckle of the six-point seat belt. Next, I unsnapped my kneeboard with my briefing material from its place around my thigh. Finally, I pulled off my helmet and stuffed it into its bag. Relieved that we were standing down, I pulled myself up out of my seat to follow the first officer, who had already made his way to the exit door at the back of the plane.

Suddenly, the ship’s 1MC intercom crackled to life, and the order barked out over the flight deck:“Launch the Fudd!”

The order caught me unprepared, just as I was half-rising from my seat and turning to leave. For a moment, I froze. Now? Are they serious?But there was no mistake. We were going to be launched. And in a matter of seconds.

At that moment, our crew was relaxing and letting down as they secured the aircraft. Suddenly—in a split second—they had to be totally gearing up again, all physical and mental systems going into hyper-alert for the critical launch mode. Not only that, we were headed into a combat zone, at night, and in foul weather. At a time like that, blood pressure goes up; hearts beat faster, breathing becomes rapid, and anxiety levels leap.

We jumped to our seats, scrambling to complete as much as possible before imminent launch: re-fastening seat belts, hooking up parachute harnesses and leg straps, re-fastening kneeboards and jamming our helmets back on our heads. What we didn’t complete now would have to be done after launching.

I switched on the ignition, moved the mixture to rich, heard the whine of the starters turning the engines over, counted six blades, pushed the master switch on, then flipped the right magneto switch to “Both” and hoped the engine would start. It caught and roared back to life. Quickly, as I repeated the process for the left engine, I checked the cat officer, who was already making the overhead circling motion, to bring both engines to full takeoff power.

I checked my engines for full power and signaled with my running lights that I was ready. With that the catapult flung my crew and me off the deck and out into the void of the night sky.

But I wasn’t looking at the sky . . . or the sea either. My eyes locked onto the attitude gyro, to position the aircraft in a five-degree climb.

I cleared the ship’s bow with a quick turn to the left, and then resumed the heading of the ship.

I checked in with Combat Information Center (CIC) to get our range and heading, the current situation, and the last known position of the Maddox and Turner Joy.

I had no way of knowing that hours later, based on reports of alleged North Vietnamese attacks that night on the Maddox and Turner Joy—combined with the reports of the confirmed attacks two days earlier—President Lyndon Johnson would order 64 aircraft from the U.S. carriers Constellation and Ticonderoga to make retaliatory bombings against selected North Vietnam bases.

I didn’t realize I would be involved in happenings that would lead our nation, ultimately, into the Vietnam War.

Over the Gulf

It took us about an hour to get to the general operating area, and during that time, I reviewed our orders: We were to provide overhead air cover for the Maddox and Turner Joy. Ordinarily that would have meant locating the destroyers and providing direction for the aircraft operating in the area.

But there were more surprises in store that night.

While still en route to the station, we soon realized, by listening to CIC, that there were no jets coming from the “Connie,” at least not at that time. I assumed it had something to do with the weather, but never knew for sure.

That significantly changed our situation. Without the Constellation’s jets, what would our role be?

We still had the task of locating the destroyers and the PT boats, but with the poor visibility and high seas creating false readings, would we be able to find them?

About eight to twelve jets from Ticonderoga were milling about in the area. There was confusion and we were hearing a lot of chatter. Ordinarily, under those circumstances, Ticonderoga’s jets would have been under the control of the destroyer Maddox, or Ticonderoga’s E-1B radar plane.

But neither of these options would work that day.

We learned from Ticonderoga’s E-1B that it was at her ship for recovery.

It was clear Ticonderoga’s aircraft were without direction. The thought was troubling. Without control from that ship’s E-1B, there was a risk of aircraft colliding, unless the Maddox was filling that role.

Then we heard from the Maddox on our radio: “Overpass. This is Maddox. Our radar is down.

Can you take over the control of the Ticonderoga’s aircraft?”

‘We Have To Get Control Of These Airplanes’

I quickly realized the grave danger inherent in the situation. With less than ideal flying conditions and the lack of Maddox control, the situation was a mess, and a very hazardous one.

The last thing I wanted to see was our jets strafing our own destroyers or colliding with each other. I talked with Al, our radar-intercept operator. “Before we can attempt to vector anyone over any target, we have to get control of these airplanes.”

Al agreed and suggested a plan. It sounded like it would work, and I said, “Let’s do it.”

With that, Al got on the radio and addressed the Ticonderoga jets. “Everyone, listen up. This is Overpass 010. I am assuming control. First, stop all this chatter. Section leaders, assemble your aircraft. I will be putting you all in holding. I will need one aircraft to search for the PT Boats.

As nearly as I can remember his exchange with the jets went something like this:

“Overpass 010. This is Screaming Eagle 01. I’m senior pilot out here . I’m your bloodhound.”

“Eagle 05. This is Eagle 01. You are now section leader of our flight. Assemble your chicks.

Overpass 010 is your control. Report to him when your chicks are mustered.”

“Eagle 01. This is Overpass 010. Turn right to 020 degrees. Your spook is 22 miles. Descend to

1,000 feet. Report level, weapons safe. If we find a spook, I’ll vector you for a re-attack. We’ll go weapons hot at that time.

“Roger, 010. Eagle 01 copies. I’ll report level angels 1. Weapons safe.”

“Roger, Eagle 01. Anticipate dropping flare one mile short of spook.”

“Roger. Eagle 01 is under my control; and 05 is mother hen. 05, stand by for holding instructions. Return this frequency when finished assembling your chicks.”

“Roger. Eagle 05 copies.”

In this way, by assigning aircraft to sections, Lt.j.g. Drum took a scene of chaos and restored order. He continued searching for the PT boats, using the Ticonderoga’s aircraft, and vectoring them over several possible targets, but each time the results were same—negative contact. During our entire time on station, there appeared to be no serious threat to the Maddox or the Turner Joy.

The initial confusion from the reported attack eventually ended, as did the evasive maneuvering of the destroyers. An uneasy calm settled over the area, and the Ticonderoga recalled her aircraft back to the carrier. We had not seen any PT boats, nor had the aircraft from the Ticonderoga seen any. Since our time on station was up, we headed back to the Constellation for recovery.

After trapping aboard, and having an initial debrief, I immediately went to my quarters and crashed. When I awoke several of hours later, the Connie’s aircraft that had carried out the strike on the North Vietnamese bases had already returned. I went to our Ready Room for a briefing and learned that the Connie had suffered two losses.

Lt. Richard Sather’s A-1H aircraft was shot down and Sather was killed while attacking a PT boat base. The second loss was Lt. (j.g.) Everett Alvarez, Jr.who was captured and spent the entire war as a prisoner of war.

During my tour of duty aboard the Constellation, I was also the Intelligence officer for our detachment. As such, I saw urgent messages from President Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to the area commanders, directing them . . . in what seemed to be something between an order and a plea . . . to find proof—pieces of metal or wood—anything that would verify that there had had been an attack by the North Vietnamese that night.

Reflecting on my own experience and observations as a part of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, and because of the lack of any evidence of an attack, it seems likely that the Vietnam War was a war that was declared based on an attack that may not have occurred.

A very sobering thought.