U.S. Army Pfc. Bradley E. Manning, the soldier accused of the largest leak of state secrets in U.S. history, plans to speak in a pretrial hearing this week. It will be his first opportunity to speak publicly since his arrest in May 2010.

Manning is accused of giving the anti-secrecy organization WikiLeaks thousands of documents related to the ongoing war in Afghanistan.

While Manning’s case is the most prolific leak in U.S. history, he is far from the first.

1953: Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Julius Rosenberg worked for the U.S. Army at the Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, NJ until Army officials discovered he had ties to the Communist Party in 1945. During his tour at Fort Monmouth, research was conducted on electronics, communications, radar and guided-missile technology. Moscow recruited Rosenberg in 1942, according to a 2003 book by Alexander Feklisov, his Soviet handler.

Rosenberg passed countless technical documents to the Soviets and became the head of a spy ring that included other Army engineers, among them—according to Feklisov—Rosenberg’s brother-in-law David Greenglass, who worked on the Manhattan Project. When the Soviets developed their own nuclear weapons with remarkable speed, an investigation discovered multiple classified technical documents had been provided to Soviet scientists through Greenglass and others involved in the Manhattan Project. Greenglass was on vacation in Mexico when the Rosenbergs were arrested. He was extradited, tried, and sentenced to 15 years in prison. After serving 10 years he reunited with his wife; they still live in New York. On 5 April 1951 Rosenberg and his wife, Ethel, were sentenced to death for their crimes. Their execution in June of 1953 marks the only time U.S. citizens have been so punished for espionage.

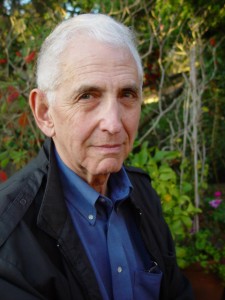

1971: Daniel Ellsberg

In 1967 Daniel Ellsberg, a former Marine Corps officer with a PhD in economics from Harvard, joined the RAND Corporation on a top-secret study of U.S. decision-making in Vietnam, authorized by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. In 1969 Ellsberg, photocopied the 7,000 page study and gave it to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee; in 1971 he gave it to The New York Times, The Washington Post and 17 other newspapers, he said in his autobiography. The study would come to be known as the Pentagon Papers. The document, “demonstrated, among other things, that the [Lyndon] Johnson administration had systematically lied, not only to the public but also to Congress, about a subject of transcendent national interest and significance,” said Times editor R. W. Apple Jr. in 1996.

President Nixon and his administration attempted to stop the continued publication of the document in newspapers, and took The New York Times to court when the newspaper refused to cease publication of the study. The right of the press to publish the papers was upheld in The New York Times Co. v. United States on 30 June 1971.

Ellsberg was brought to trial for making the leak. When he surrendered to the U.S. States Attorney’s office for the District of Massachusetts he said, “I felt that as an American citizen, as a responsible citizen, I could no longer cooperate in concealing this information from the American public. I did this clearly at my own jeopardy and I am prepared to answer to all the consequences of this decision.” The charges brought against him carried a maximum sentence of 115 years. However, during his trial it was brought to light that President Nixon had ordered a break-in of some offices where Ellsberg worked in an attempt to find documents which could be used to discredit him. Evidence of illegal wiretapping was also discovered. The judge in the case said he had no choice but to dismiss the case against Ellsberg: “The totality of the circumstances of this case which I have only briefly sketched offend a sense of justice. The bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.” Ellsberg remains active in U.S. politics to this day. He runs a political blog at http://www.ellsberg.net/ and is a senior fellow of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.

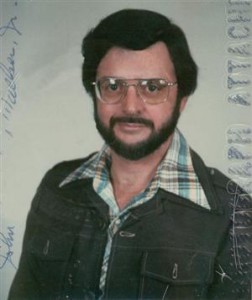

1984: John Walker

Senior Warrant Officer John A. Walker joined the Navy in 1955 and obtained a top-secret cryptographic clearance. “The farce of the Cold War and the absurd war machine it spawned,” he wrote in his memoirs, “was an ever-growing pathetic joke to me.” He began his career as a spy by photocopying a classified document and walking it to the Soviet Embassy in Washington. From 1967 to 1975 Walker provided a flood of naval secrets to the Soviets. After his retirement, he became the head of a ring of active-duty spies, recruiting his own son in 1983. The younger Walker copied 1,500 documents for the KGB from the USS Nimitz.

In 1985, Walker’s ex-wife reported him to the FBI. His daughter testified against him. Subsequent searches of his home turned up plentiful evidence of the spy ring. His initial accomplice, Jerry Whitworth, was given 365 years in prison. Arthur Walker, a brother who had provided repair records on certain warships as well as damage-control manuals, was given three life terms. John Walker himself received a life term, and his son received 25 years. In February of 2000 Michael Walker was released for good behavior. John and Arthur will be eligible for parole in 2015. Oleg Kalugin, the KGB officer who had first managed Walker, wrote Walker’s case was, “by far the most spectacular spy case I handled in the United States.