STOCKHOLM – Two months into its membership in NATO, Sweden is retooling its defense after 200 years of military neutrality.

Not since Napoleon’s 1812 campaign in Russia has Sweden formally allied militarily with another country, Minister of Defense Pål Jonson told reporters earlier this month. Since the eve of World War II, Stockholm used a porcupine strategy of “armed neutrality” relying on the country’s indigenous defense, aerospace and shipbuilding industries to ward off Russian aggression. That changed after Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

“Going into an alliance is of course a big change. Policy-wise it’s a big change, mentally it’s a big change,” Jonson told reporters at defense firm Saab’s headquarters. “And [we have] to remember that we’re not necessarily going to be defending Sweden from inside Sweden, but from a distance, and we’re going to be doing it as a solidaric ally.”

Now NATO planners can use what was “white space” on their maps to craft a unified defense of the Nordic region, Sweden’s deputy chief of defense staff Rear Adm. Jens Nykvist told reporters. Sweden also brings more than a hundred years of experience operating submarines in the Baltic Sea – the doorway to Russia’s largest port of Saint Petersburg, Nykvist said.

In parallel with joining NATO, Sweden is also finalizing an agreement with the U.S. to host American military units, double its defense spending and craft a new national security strategy that factors in its 31 new treaty allies, Jonson said.

“This is a direct consequence of Russia’s illegal, unprovoked full-scale invasion of Ukraine,” Jonson said. “This is the mother of all unintended consequences for Russian strategic thinking.”

Since Sweden and Finland joined NATO combined with Norway and Denmark, they form the first contiguous Nordic military alliance in more than 500 years and might be Sweden’s most significant contribution to the alliance, one expert told USNI News.

While Sweden has developed a domestic military industrial base, its standing military is small relative to the other members of NATO. The Swedish Armed Forces total 25,000 and about 2,500 sailors make up the Swedish Navy.

“Sweden’s most important contribution to NATO will be its territory for deterrence and defense purpose,” Marta Kepe, a researcher at RAND, told USNI News last week. “Sweden can have an important role as an enabler, and as a basing and staging area for U.S. and allied forces. Sweden can help NATO prevent Russia’s ability to shape the regional environment for a potential conflict and repel a Russian invasion.”

Baltic Sea is Not a ‘NATO Lake’

After Finland formally joined NATO last year, European pundits started referring to the Baltic as NATO’s lake, encircled by Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Compared to NATO, Russia has a minuscule coastline on the Baltic south of Finland and in Moscow’s exclave in Kaliningrad between Lithuania and Poland.

But the proximity of eight treaty allies around the Baltic does not mean the 145,000 square mile body of water is uncontested, Nykvist told reporters.

“Some people tried to say Sweden and Finland now being part of NATO makes the Baltic like a NATO lake. I would say no, it’s not,” he said. “It’s not, because we have the Russian bases.”

Russia’s Baltic Fleet is headquartered on its sliver of Baltic coast and is key to Moscow’s power projection in the region.

On Wednesday, the head of the Swedish Armed Forces, Gen. Micael Bydén, told German news outlet RND that Russian President Vladimir Putin was set on controlling the Baltic Sea.

Bydén singled out the central Swedish island of Gotland as key to Russia’s goal of dominating the region.

“I’m sure that Putin even has both eyes on Gotland. Putin’s goal is to gain control of the Baltic Sea,” Bydén told RND. “If Russia takes control and seals off the Baltic Sea, it would have an enormous impact on our lives — in Sweden and all other countries bordering the Baltic Sea. We can’t allow that.”

Russia’s naval presence in the Baltic is buttressed with a fleet of merchant vessels that Swedish officials claim are part of a hybrid warfare campaign. The shadow fleet is equipped with sophisticated communications gear that military officials in Stockholm say is unnecessary for merchant ships. The fleet has operated inside Sweden’s economic exclusive zone off of Gotland, according to a report from the Center for European Policy Analysis. The shadow fleet is also suspected of shipping illicit Russian oil through the Baltic, violating sanctions.

Beyond the Russian Navy and shadow fleet, increased commercial shipping and underwater infrastructure like communications cables and pipelines are making operations in the Baltic Sea more complicated, Nykvist said.

“There is a lot of density of traffic. It’s roughly 4,000 ships moving around every given minute in this region,” he said. “It’s coming from [the] St. Petersburg area and going out and back. That’s one of the main routes for Russia regarding oil and energy products.”

Merchant shipping on the Baltic Sea is also critical to the Nordic countries. The western port of Gothenburg, which is the main container port for Sweden and Norway, is being dredged to accommodate heavier ships. Instead of being the last stop for ships from Asia, the port will be the first for ships coming across the Arctic.

Sweden is also anticipating a Northeast passage will eventually allow commercial ships to come to Europe from Asia through the Arctic. Gothenburg will become one of the first spots for ships coming across the Arctic as opposed to the last for container ships coming through the Red Sea through the Suez into the Mediterranean Sea.

The threat of electronic warfare is also increasing regionally. In the southern Baltic, near the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, GPS jamming of ships and aircraft has increased, resulting in high-profile instances of aircraft and ships falling victim to spoofing.

“We see examples of GPS jamming, for instance, in this area,” Nykvist said. He would not go as far as to say where the jamming originates, but many open-source intelligence analysts have pointed to Kaliningrad.

A Century Undersea

Sweden launched its first submarine, Hajen, in 1904 and has developed submarines consistently since then.

“I would claim unique assets and capabilities when it comes to operating [in] the Baltic Sea because we’ve been working for decades under the water with our submarines on the surface with our surface combatants,” defense minister Jonson told reporters.

The brackish and shallow Baltic Sea is a playground for small attack submarines. Sensors used to find an adversary’s boats in the salty and deep Atlantic don’t perform well. The differences in temperature create layers under the water that hide submarines from active sonar, Cmdr. Peter Östbring, chief of staff of the Swedish Navy’s 1st submarine flotilla, told USNI News earlier this month during a trip to Karlskrona in southern Sweden.

“The complexity of the sea in our surrounding areas is… to our advantage,” Östbring said.

“That [is] the reason why our submarines are the size they are: because they’re optimized for operating in shallow waters.”

The Swedish submarine fleet consists of four submarines: three Gotland-class 1,600-ton air-independent attack boats built in the 1990s and the older 1,500-ton HSwMS Södermanland. All four boats have been upgraded with an air-independent propulsion system that allows the boats to operate underwater for extended periods.

The shallow Baltic Sea is about 230 feet deep on average, making seabed warfare a major consideration in the region, with major utilities under the surface like communication cables and gas and oil pipelines.

“The concept of seabed warfare is a fairly new concept … the learning curve is steep,” Östbring said. “We are moving ahead quite fast to get more knowledgeable, create capabilities to add on to a higher level of maritime security, because of the critical mass of the things that are at sea and on the seabed.”

The most famous example of an undersea incident in the Baltic was the still-unsolved attack on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in 2022. In October, a gas pipeline and communications line from Finland to Estonia were severed.

“The main goal of the submarine force is to, to not stand guard, close to the pipeline but to create over time a recognized maritime picture so that other parts of the Navy and Swedish society are aware of what actors are in the area, what they’re doing, and what potential threat they might cause,” Östbring said.

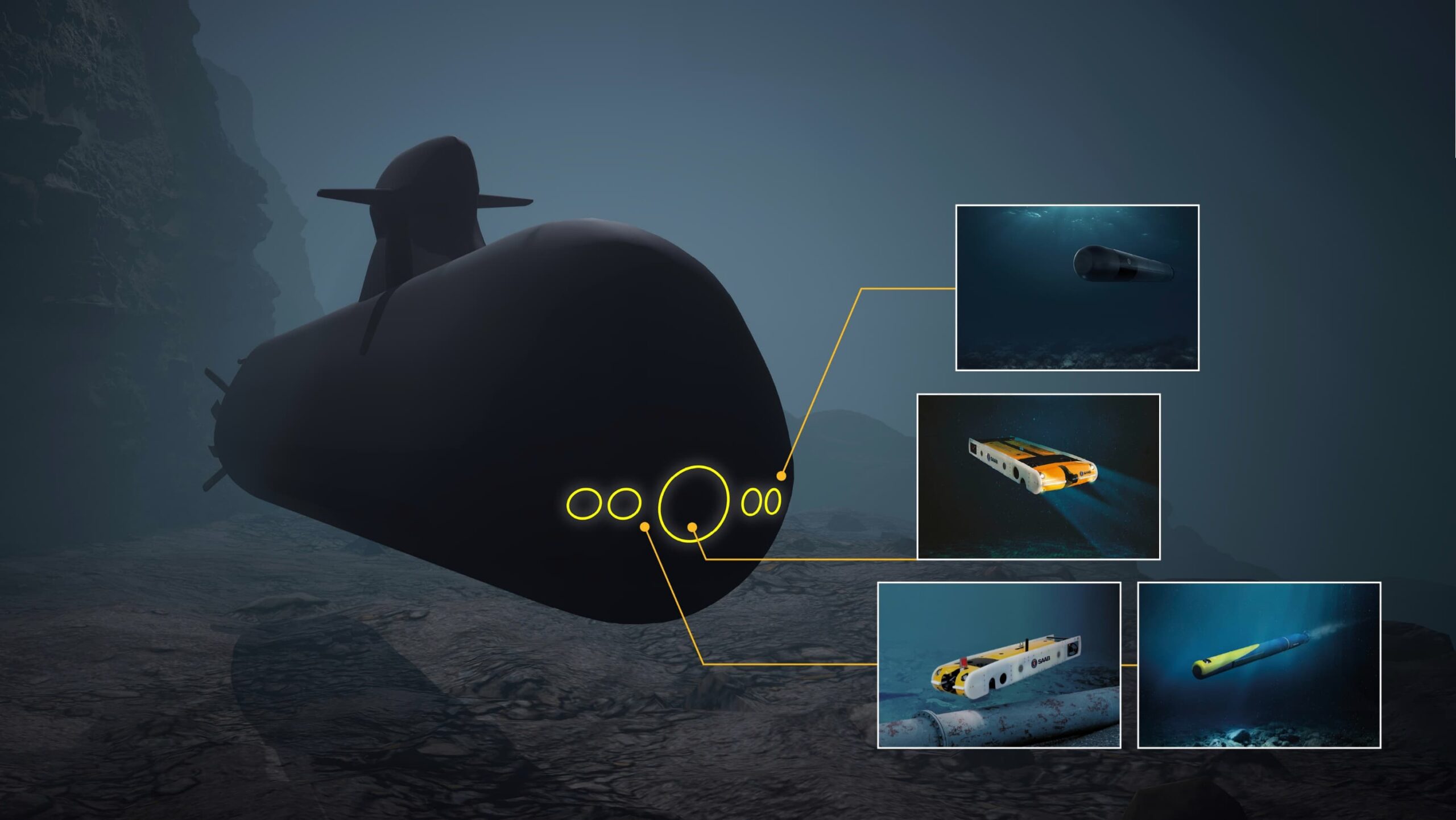

To that end, the Swedish Navy is developing a new class of A-26 Blekinge-class boats that can operate for weeks at time in the shallow depths of the Baltic. The two boats, which have been several years in the making, lean into seabed warfare with the bows of the future HSwMS Blekinge and HSwMS Skåne featuring a large airlock to deploy either divers or unmanned underwater vehicles.

In addition to undersea warfare, the Swedish Navy also brings extensive experience with mine countermeasures. The Baltic Sea has an estimated 40,000 to 50,000 unexploded sea mines from World War I and World War II.

“It’s a time-consuming task to clear those mines. Most of the mines built 100 years ago were superb quality, because …when we demolish them today they still detonate with full force as they were intended 200 years ago,” Östbring said.

“I would say our demining efforts [haven’t] changed. The thing that has changed are there no contacts with Russia.”

Note to readers: USNI News traveled to Sweden at Saab’s invitation, but paid for our travel and accommodations in line with our ethics policy.