BALTIMORE, Md. — The furious activity inside the cruise terminal at the Port of Baltimore on Monday was far from normal.

Though the area often sees cruises throughout the week, where throughout the week passengers walk through the doors toward their cruise ship or come back through Customs and Border Protection.

Cruises are halted and the terminal’s lobby has been transformed into a command post for the Joint Information Center under the unified command, set up by the Coast Guard, to tackle the wreckage of the Francis Scott Key Bridge.. The lobby where passengers would typically check in was filled with tables where people in red vests sat. In rooms farther back, one cubicle was set up for the Coast Guard, another for the Navy. Paper signs labeled JIC adorn the temporary walls of the cubicles.

In one of the back cubicles, a few sailors with the Navy’s Supervisor of Salvage and Diving unit examined sonar pictures of the Key Bridge’s submerged wreckage that were tacked to mobile walls.

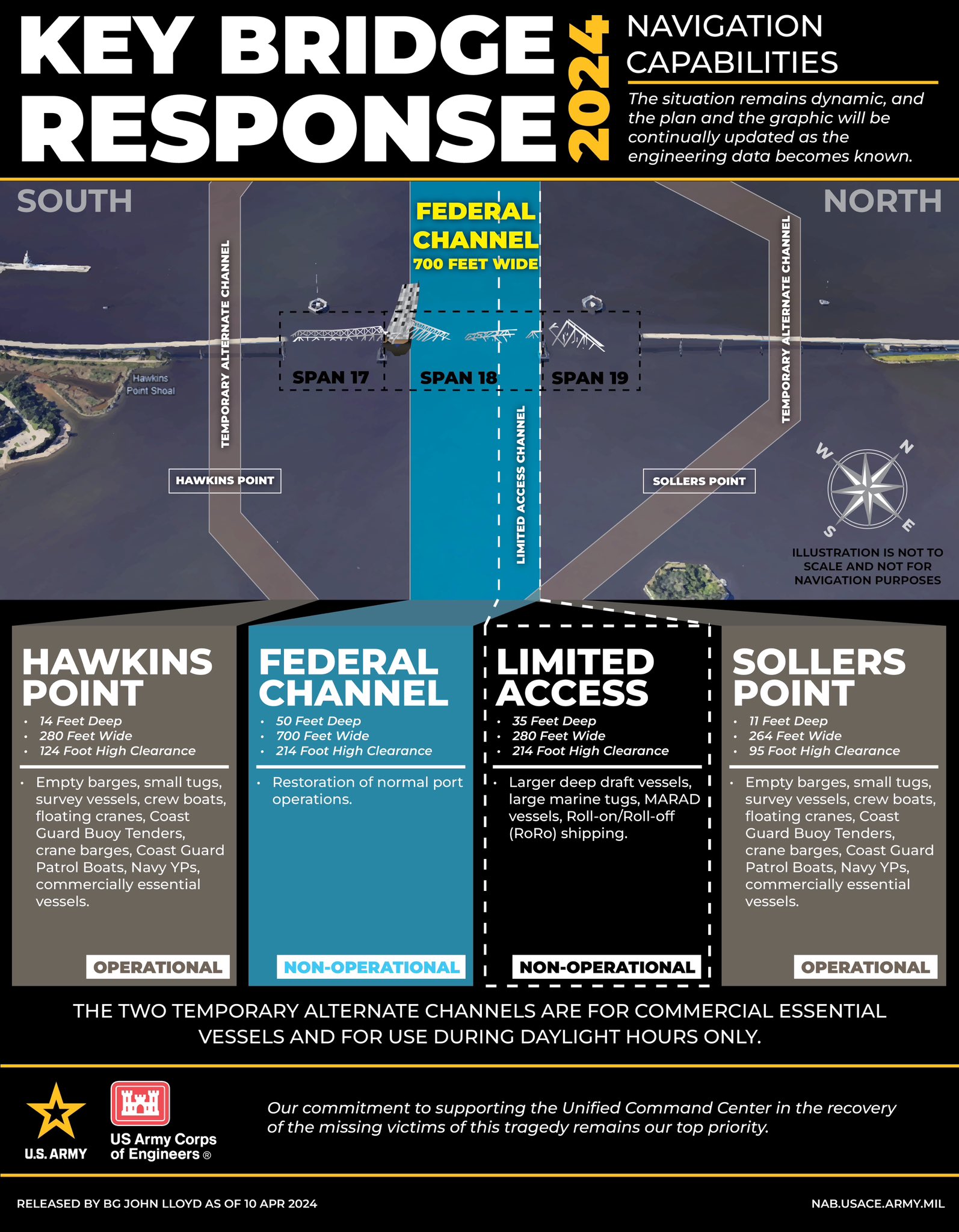

The Navy’s Supervisor of Salvage and Diving is one of the federal units called in to assist the unified command – comprised of the Coast Guard, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Maryland Department of the Environment, Maryland Transportation Authority, Maryland State Police and Witt O’Brien’s (a management company representing MV Dali’s managers) – with cleaning up the bridge wreckage and opening the channel. Last Thursday, the Army Corps of Engineers said the Port of Baltimore and the channel will be open by the end of May.

From the cruise terminal, the Key Bridge and the giant container ship tangled in the wreckage is a distant, unmissable blob on the horizon.

Still, the visibility is better from the cruise terminal than underwater where divers are extracting the bridge’s wreckage from the mud. Visibility is 1-2 feet underneath the water of the Patapsco River, where the twisted metal of the Key Bridge lays, Capt. Sal Suarez, commander of Supervisor of Salvage and Diving, told USNI News.

Divers in the channel that falls under federal control are contracted by the Navy’s Supervisor of Salvage and Diving, which also brought in three contracted cranes, including Chesapeake 1,000, a crane with links to the CIA.

Navy Supervisor of Salvage and Diving (SUPSALV) arrived at the Key Bridge collapse site on March 26, the day Dali lost power and sailed into the bridge, causing it to collapse into the water and on top of the ship. Six men working to fill potholes on the bridge died in the collapse. Three of the men’s bodies have been recovered.

The Navy-associated divers do not recover any human remains found in the wreckage, Suarez said. If divers come across a body, they alert the teams on top, who in turn alert Maryland State Police, he said.

For some divers, this is not their first operation involving casualties, he said, and even if the waters are murky, they will know if they come across a body.

Safety is the priority, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore said at an April 3 press conference.

“We have to move fast, but we will not move careless,” Moore said. “My directive is to complete this mission with no injuries and no casualties.”

Diving operations

Suarez is on temporary duty assignment to Baltimore as part of the cleanup effort.

The day-to-day operations of the salvage team will fluctuate, he said, but his day will typically start before the sun rises.

The salvage effort supervisors meet at 6:30 a.m. for a meeting, Suarez said. They go over plans for the day and talk through water space management.

“There’s a lot of equipment out there,” Suarez said. “We want to make sure no one gets in anybody’s space, everything is handled safely in the water space.”

Then the supervisors walk through the scheduled plan of action whether it is rigging, cutting or lifting operations.

The day usually ends around 5 p.m. And repeat. As Suarez put it, he lives just far enough to make the drive to and from Baltimore impossible as a daily commute.

The Navy’s Supervisor of Salvage and Diving contracts divers and cranes for recovery projects as part of its overall mission. Some of the operations are Navy focused, such as recovering downed aircraft from the water. Suarez’s personal experience as a Navy diver is in deep ocean recovery, he said.

No active-duty Navy divers are clearing the Key Bridge wreckage.

Typically, one diver goes down at a time, Suarez said, although two are sometimes needed for safety reasons. At all times they are in contact with the topside team.

“That’s the buddy system, where the divers can’t really see a whole lot, and they’re basically being driven by their umbilical, their comms,” Suarez said.

Removing the bridge from the Patapsco River is a dive-intensive operation, Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Linda Fagan told an audience at Sea Air Space, USNI News reported.

“It’s a 940-foot container ship,” Fagan said. “There was a gas pipeline running underneath the bow of the ship that had to be turned off. There are power lines right over the stern of the ship as they begin to consider how to make the ship lighter so it can be refloated and removed. There’s just a host of complexities around the recovery.”

Then there is the visibility challenge.

When the divers first went into the water, they started with diver surveys. That’s when the team realized just how bad the visibility was down by the wreckage, Suarez said.

“It’s pretty murky on the bottom,” Suarez said.

The murkiness in the water is caused by the 4 to 5 feet of mud and loose bottom of the Patapsco River, Army Corps of Engineers Baltimore District Commander Col. Estee Pinchasin said at an April 3 press conference.

Divers are also working in darkness. Pinchasin said using lights would be like driving in a snowstorm with high beams on. Debris in the water would reflect the light beams back, blinding the divers.

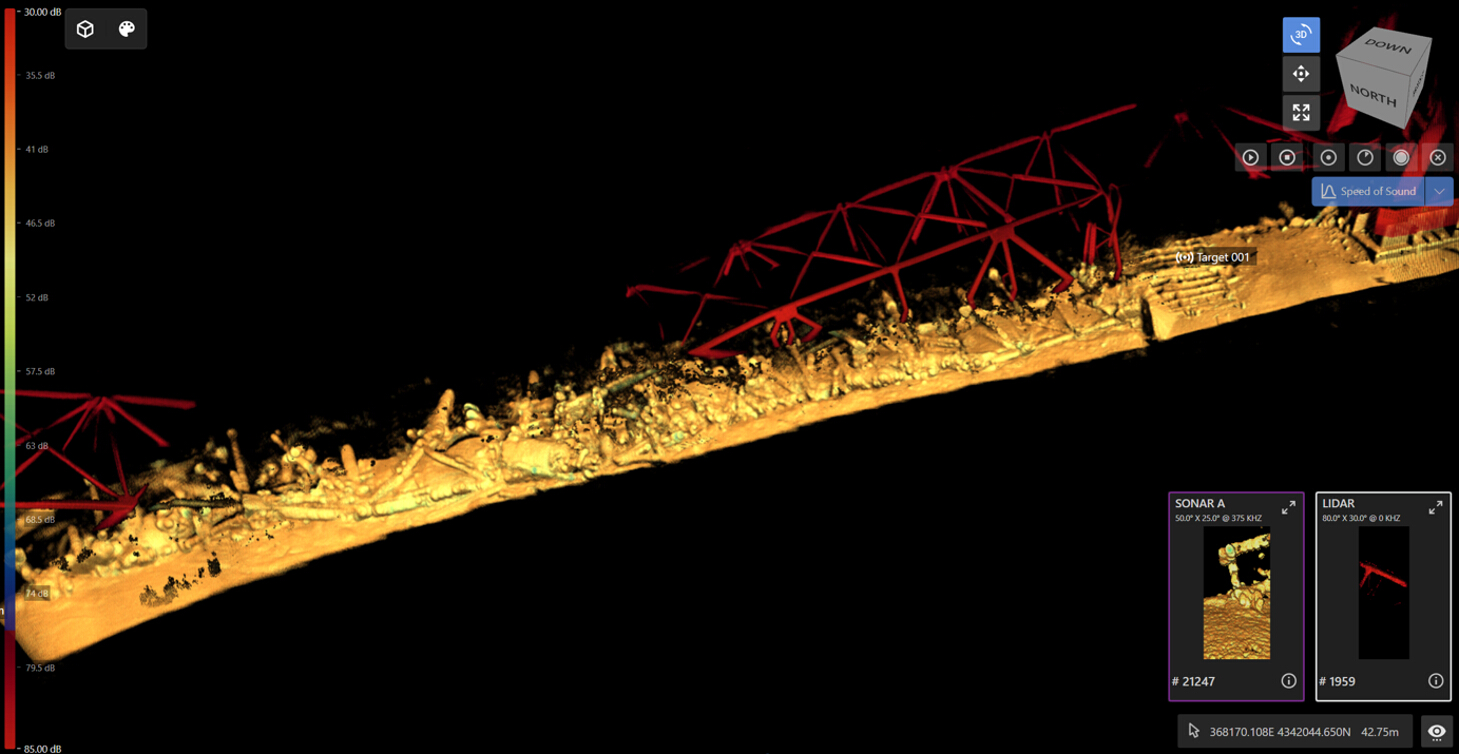

So the Navy contracted with CODA Octopus to lower a sonar system to the wreckage and create a map. Parts of the bridge have settled in the mud, he said. Parts of the roadway, which used to hang as part of the tension bridge, are now sitting on top of trusses, Suarez said.

“The initial mapping is done,” Suarez said. “And that allowed us to really understand how bad it was down there.”

The sonar images included both the bridge parts above and below the waterline. Guided by the team up top, the divers are checking how much of the bridge is still connected, Pinchasin said on April 3.

Those images were then be verified by the divers in the water, Pinchasin said at the April 4 press conference. It is unclear from the images whether any parts of the wreck are pulled taut, and the unified command does not want a piece to spring back when the machines cut, she said.

“When you look at the skyline and you see those large spans in the water, it looks like they just fell,” Pinchasin said in the press conference. “And so you think of how Jenga falls or how pick-up sticks fall and you think you’ll just take them apart. But the wreckage is so mangled, cantilevered and bent that within those piles, within that wreckage, there may be forces that came down with it.”

Lifting the bridge

Now that the initial mapping is done, workers can start cutting bridge pieces, Suarez said.

The steel and twisted pieces of the bridge must be cut small enough to lift them out of the water and onto barges, which will take the bridge chunks shoreside. SUPSALV contractors have hydraulic shears and diamond wire saws to make the cuts.

The cranes send the equipment, which includes shears or wires, down to the bridge wreckage. Then a diver ensures the equipment is in the right spot. Oncethe diver is back topside, cutting commences, with a diver back in the water to assess following the cut, Suarez said.

The unit uses shears or wires instead of torches or other diver-intensive methods so the diver can be out of the water and safe in case a piece of bridge moves, he said.

The pieces must be cut smaller than 1,000 tons, which is the most the biggest crane contracted by the Navy unit, Chesapeake 1,000, can lift. Most pieces will likely be smaller, but the team is still looking to bring up pieces as big as possible.

“You could cut all the trusses and make a lot smaller pieces, but we’re trying to be as efficient and effective as we can,” Suarez said.

To take the bridge apart, state and federal teams and their corresponding contractors have to address the metal under and above the water.

The state contractors began tackling the north portion of the bridge on Saturday, March 30, using an exothermic cutting torch to cut through above-water pieces that a crane then lifted and offloaded at a disposal site, according to a unified command release.

Suarez did not say when they’ll start lifting bridge pieces.

Continuing steps

On Sunday, salvagers began removing crates from MV Dali. Efforts continued Monday when USNI News visited the wreckage site. The Unified Command is removing debris to open a larger channel for commercial traffic, Coast Guard Capt. David O’Connell said in a unified command release. More than 30 ships already passed through the two smaller temporary channels. The team plans to remove the containers so it can refloat and move Dali.

As of Thursday, 38 containers had been removed.

The command’s top priority is reopening the deep federal channel, Coast Guard. Rear Admiral Shannon Gilreath said during the April 3 news conference. The second priority is refloating Dali, and the third is removing the debris from the waterway, he said.

Delays in the salvage efforts will likely mean military sealift command ships and Coast Guard ships are stuck respectively in the Port of Baltimore and Coast Guard Yard in Curtis Bay longer. More money could be lost as the shipping industry adjusts to temporarily having one less port.

But the operation is at the mercy of Maryland weather

Right now, Suarez said, the team’s biggest obstacle is the difficult weather Maryland saw last week. Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday were clear and in the 70-80s. Rain hit again Thursday with Friday expecting more in addition to high winds, according to the weather forecast from NOAA.

Divers can go down when it rains, but wet conditions can cause safety issues for heavy equipment like the cranes. High winds, an issue last week, and lightning can halt all operations, Suarez said.

Weather in Maryland is unpredictable. Sunshine one day, rain the next. Even the rare April snowstorm.

For a mission aimed at a fast timeline, weather is the one thing that cannot be controlled.