The Navy and U.S. Transportation Command are sending salvage equipment to help find a submersible that went missing while trying to travel to the wreck of RMS Titanic, the Coast Guard announced Tuesday.

The U.S. Coast Guard set up a unified command Monday that brings together the U.S. and Canadian coast guards, the U.S. Navy and the Canadian armed forces to coordinate rescue efforts. The unified command is working with the U.S. Navy and TRANSCOM to determine which naval assets to send, Capt. Jamie Frederick said during a Coast Guard District news conference on Monday.

“This is a complex search effort, which requires the use of subject matter expertise and specialized equipment,” Frederick said. “While the U.S. Coast Guard has assumed the role of search and rescue mission coordinator, we do not have all of the necessary expertise and equipment required in a search of this nature. The unified command brings that expertise and additional capability together to maximize effort in solving this very complex problem.”

The Navy is sending a Flyaway Deep Ocean Salvage System, as well as subject matter experts, the sea service said in a Tuesday afternoon statement.

The Flyaway Deep Ocean Salvage System is a “motion compensated lift system designed to provide reliable deep ocean lifting capacity for the recovery of large, bulky, and heavy undersea objects such as aircraft or small vessels,” according to the statement.

The Navy previously used the salvage system to recover an F-35C Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter that crashed into the South China Sea after a ramp strike on USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70), USNI News previously reported. The Navy was able to recover the aircraft from 12,400 feet.

Both the salvage system and subject experts are expected to arrive at St. Johns, Newfoundland, Canada, tonight.

TRANSCOM also sent three C-17 aircraft to transport commercial cargo and equipment for the rescue, Deputy Pentagon Press Secretary Sabrina Singh said in a statement. All three departed Buffalo, N.Y., for St. Johns.

“U. S. Transportation Command is supporting the search effort with (3) C-17 aircraft that are transporting commercial, rescue-related cargo and equipment from Buffalo, NY to St Johns, Newfoundland. As of 4:30 pm eastern time today, all three aircraft have departed Buffalo, and the last aircraft is scheduled to land at St. John shortly.”

Canadian Coast Guard and Royal Canadian Air Force aircraft have been part of the surface search. RCAF Cp-140 Aurora anti-submarine warfare aircraft have dropped sonobuoys in an effort to search below the surface for Titan and the five aboard.

MV Deep Energy, a 194-meter pipe-laying vessel that has remotely operated vehicle capabilities, arrived Tuesday to help with the search, Frederick said. The vessel started an ROV dive with operations ongoing.

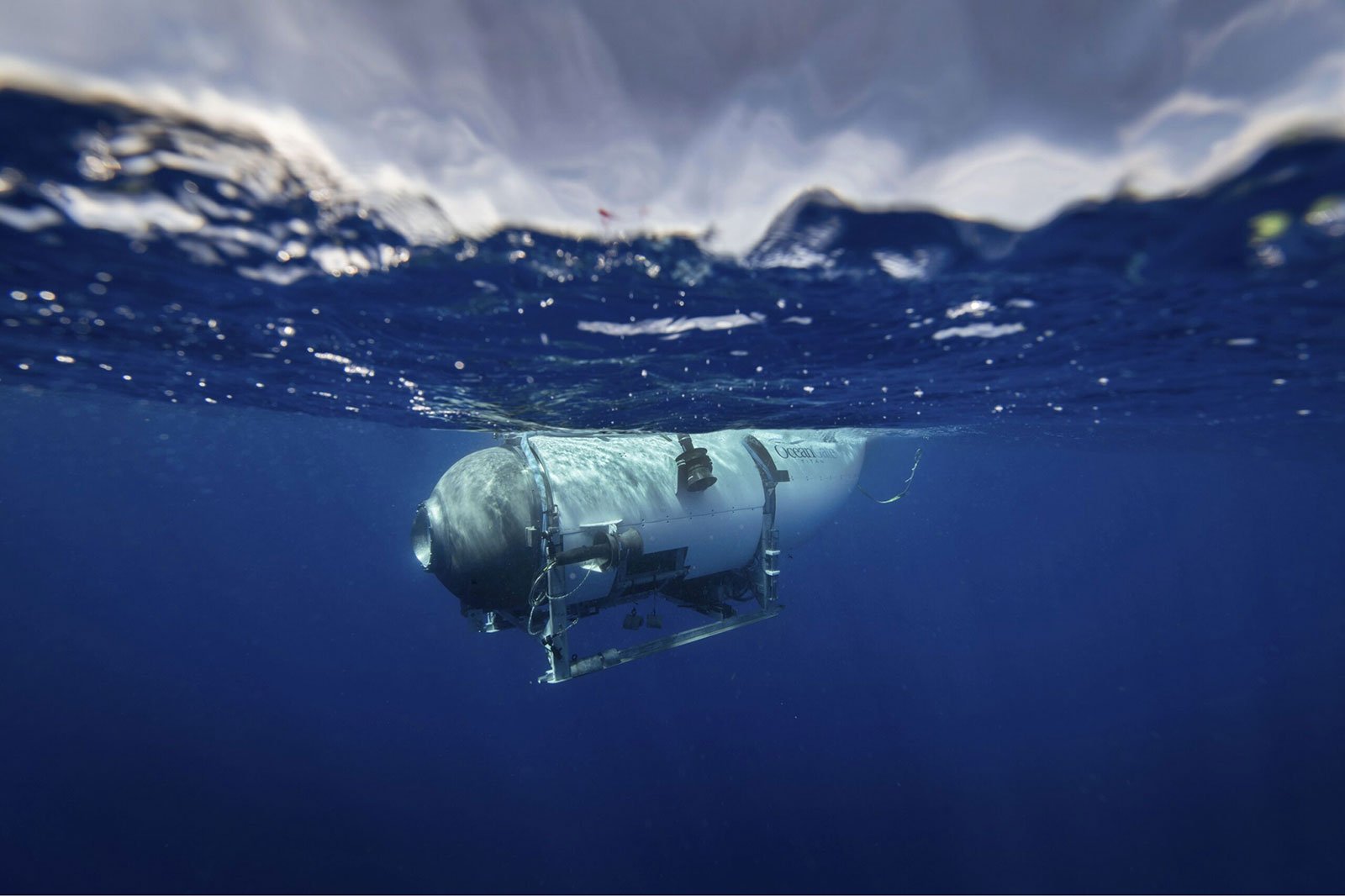

The Titan submersible, operated and built by company OceanGate Exploration, departed Friday from St. John’s Newfoundland, Canada aboard former Canadian Coast Guard ice breaker MV Polar Prince. On Sunday, Titan attempted to reach the wreck in the late afternoon and was reported missing about an hour and 45 minutes into the dive by the team aboard Polar Prince.

The crew included a pilot with OceanGate and four passengers the company refers to as “mission specialists,” who paid a $250,000 fee to descend on Titan to survey the wreck as part of an eight-day expedition.

It’s not clear how much air is left in the submersible, Frederick said, but the estimate is about 40 hours.

‘Trying to Find a Minivan in the Atlantic’

There are likely three scenarios for the submersible after it lost contact with its corresponding ship on the surface, said Sal Mercogliano, associate professor of history at Campbell University.

The vessel dropped its weight and bobbed to the surface of the ocean. It could have sunk to the bottom. There could have been a catastrophic failure, where the integrity of the submarine is breached, which would mean the rescue efforts become recovery ones.

If the vessel is bobbing on the surface – the best case scenario, Mercogliano said – the passengers inside, including British billionaire Hamish Harding and Paul-Henri Nargeolet, the underwater research director for RMS Titanic, Inc., would not be able to escape the submersible because they are bolted inside.

There is limited breathable air inside the submersible, Mercogliano said, which puts a time limit on rescue efforts. Even in the situation where the submersible dropped its weight and returned to the surface, the U.S. and Canadian coast guards have to find a relatively small object in the Atlantic Ocean.

“You’re trying to find a minivan in the Atlantic right now,” Mercogliano said.

If the submersible sank to the bottom, the second of the scenarios, it makes rescue efforts more complicated, he said.

The Navy usually tracks submarines, which are larger and operate closer to the surface than OceanGate’s submersible. If the Navy were to send assets to assist with rescue efforts, the equipment would not easily able find the submersible due to its size and the depth it sank.

“Thirteen thousand feet under the water is a whole different environment,” Mercogliano said.

The U.S. Coast Guard is currently the lead agency for the rescue efforts, but if it becomes a recovery effort, the commercial sector will likely become the lead because it has equipment better suited for the circumstances, Mercogliano said. OceanGate is also working to send another submersible out to help.

Another complication is that a cable is required to help lift the submersible, he said.

In addition to the air limit inside the vessel, if the submersible sunk to the bottom and is out of power, heat will also be an issue, he said.

If there was a catastrophic failure, it would no longer be a rescue effort but rather a recovery one.

Submersibles, like OceanGate’s Titan, are not regulated, Mercogliano said. That means there is no governing body dictating what safety features the craft requires. It’s unclear if the vessel had a rescue beacon or other way to signal for help.

Mercogliano said it’s ironic that the unregulated vessel went missing while attempting to reach the Titanic wreckage since this shipwreck led to a number of safety regulations still used today on ships.

Safety of Life at Sea, the regulations passed after the Titanic tragedy, laid out how many lifeboats are needed on a ship, as well as 24-hour radio requirements.

It’s unclear if similar regulations will come after the submersible situation, Mercogliano said. While OceanGate is an American company, the submersible launched out of a Canadian port.

According to Mercogliano, submersible companies make up a small part of the commercial sector, meaning the industry may not be large enough to regulate.