Since 2017, junior sailors assigned to aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN-73) were subject to some of the toughest living conditions in the military, according to a new Navy investigation released on Thursday.

Sailors assigned to the carrier over its almost six-year-long maintenance period at HII’s Newport News Shipbuilding experienced poor living conditions, up to three-hour commutes and isolation from their families and peers as part of life in the shipyard. Complaints about the life as a George Washington sailor, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, fell on deaf ears within Navy leadership, according to the quality of life investigation released on Thursday and reviewed by USNI News.

While Washington has been in the middle of its midlife overhaul and refueling at Newport News Shipbuilding, nine sailors died by suicide, according to Navy records reviewed by USNI News.

After years of complaints from sailors aboard and assigned to the ship, three suicides in April 2022 by sailors assigned to and aboard the carrier prompted the investigation into the quality of life for sailors aboard the carrier.

The suicides are the starkest statistic of a crew that had a high rate of substance abuse, experienced poor oversight from leadership and had a higher-than-average rate of first-tour sailors who spent their first four years in the Navy working in the shipyard, according to the command investigation overseen by commander Naval Air Force Reserve Rear Adm. Brad Dunham and released on Thursdays.

In a call with reporters on Thursday, U.S. Fleet Forces commander Adm. Daryl Caudle blamed some of the crew stress on the service neglecting to account for how an almost two-year extension of the maintenance period would affect the crew aboard.

“We got ourselves into a space that we were just not ready to understand what can happen with this length of overrun,” he said.

Navy leadership focused more on the effects of the material condition of the carrier and delays rather than the effects of an extended maintenance period on the crew, Naval Air Force Atlantic commander Rear Adm. John Meier said in his endorsement of the investigation.

“We failed to stop and account for the true costs of this process on our sailors. … We understand the ‘stuff’ and we can quantify it, test it, improve upon it, and master it almost to the level to where it becomes predictable. This is the area in which we are most comfortable,” he wrote. “While extremely important, it pales in comparison to how we take care of the people.”

Mid-Life Upgrade

George Washington is nearing the end of one of the most complex and demanding periods of the carrier’s 50-year-long service life.

Programmed into the life of each Nimitz-class aircraft carrier is a four-year repair period called the refueling and complex overhaul (RCOH). In addition to refueling the two nuclear reactors, almost every space in the 90,000-ton carrier is renovated and modernized.

The multi-billion dollar maintenance periods are done solely at HII’s Newport News Shipbuilding – an almost 140-year-old shipyard perched across the James River from Naval Station Norfolk, Va. RCOHs have historically accounted for about a third of the yard’s business, with the other two-thirds split between new aircraft carrier and submarine construction.

Unlike the new-build carriers and submarines, which belong to the shipyard until they are delivered to the Navy, the carriers in RCOH belong to the service and the ship’s crew has a major role in assisting the shipyard with the overall maintenance period.

George Washington entered Newport News Shipbuilding on Aug. 4, 2017, after being forward-deployed in Japan from 2008 to 2015. George Washington was the first Japan-based U.S. nuclear carrier to undergo a different maintenance regime from the other carriers based in the U.S., adding to the amount of work on the carrier, HII told USNI News in a statement.

Factors that extended the RCOH included, delays and changes in her RCOH planning and induction timeline due to FY15 budgetary decisions to inactivate (vice refuel) this ship; the arrival condition of the ship, which was more challenging than expected, planned or budgeted for, including growth work in significant areas of the RCOH; the requirement to remove critical parts from CVN-73 to support higher-priority, deploying aircraft carriers; and the impact of COVID-19 on the workforce and industrial base,” reads the statement.

According to Navy data and the USNI News carrier database, George Washington’s RCOH will last 34 percent longer than planned – or will deliver more than a year and half late.

Washington also entered the yard as Newport News’ other major programs were suffering delays. The carrier started RCOH a month after the Navy commissioned first-in-class carrier USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78), which would suffer continuous delays to its deployment schedule and require yard resources. During the same period, HII was also running behind on its Virginia-class submarine program and contracted delivery dates as the effects of the COVID-19 lockdowns began to hit the shipyards.

In its investigation, Naval Air Forces commander Vice Adm. Kenneth Whitesell blamed the yard for shifting resources from George Washington’s overhaul to new construction carriers and submarines.

“[Aircraft carriers] undergoing RCOH continue to experience unnecessary delays, due to both underfunding of RCOH and the shifting of HII-NNS priorities away from RCOH work to new build CVNs or submarines,” Whitesell wrote in his endorsement. “Financial incentives must be established for on-time delivery with all combat systems and ships service systems fully functional. Without on-time incentives, current delivery delays will continue, compounding the already backed-up shipyard.”

The resource problems worsened when next-in-line carrier USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74) crossed the river from Naval Station Norfolk to Newport News for its RCOH on May 13, 2021.

“Underfunding of USS George Washington RCOH and shifting of shipyard priorities to USS Gerald R. Ford created undue stress upon the crew of USS George Washington. The resulting delays and introduction of USS John C. Stennis to HII-NNS only exacerbated pre-existing strain on resources and workplace stressors of shipyard life faced by sailors,” Whitesell wrote.

“This shipyard backlog has put more CVNs and sailors in the shipyard than current HII-NNS facilities and manning can support.”

In a statement to USNI News, the shipyard said “has been, and continues to be, aggressively engaged with the Navy and City of Newport News to enhance quality of service for Navy sailors and shipbuilders at Newport News Shipbuilding. Specific examples include: improving parking and transportation options; enhancing Wi-Fi and IT services; facility improvements and modifications at buildings used by shipbuilders and the Navy; increased security presence; additional onsite food services; support for regular on-site visits by trained therapy dogs; and regular meetings with the Navy and City of Newport News.”

According to the Navy, HII was not consulted as part of its investigation.

By the Numbers

Life in a shipyard is “arduous,” a reality the Navy accepts, Meier wrote in his endorsement of the investigation. Statistics on aircraft carrier suicides between 2017 and 2022 show that 57 percent of those deaths were among sailors whose ships were in maintenance, according to the report. Of the 42 deaths, nine were George Washington sailors. USNI News previously reported that a 10th suicide may have also occurred in the time period.

Although the investigation does not indicate whether the Navy used calendar or fiscal years, suicides among aircraft carriers accounted for four out of 58 deaths, or 6.9 percent, based on Fiscal Year 2021 data, which is the most recent data available for overall suicides.

In 2019 – the worst year for suicides since 2017 – deaths among aircraft carrier sailors accounted for 12 out 74 suicides, or 16.2 percent. Of the 12 suicides, eight happened during maintenance and one was a GW sailor.

The suicide rate in the Navy has increased over the past 10 years, USNI News previously reported. The most recent available suicide rate is from the FY 2021 report, which found that the Navy experienced 16.7 deaths per 100,000 sailors, the lowest rate in five years. During 2021, there was one suicide among GW sailors.

“Increased awareness of suicidal ideations and behaviors within the organization should have triggered both concern and invasive action by the chain of command,” Dunham wrote in his investigation.

Trust in Command

In addition to the Navy not properly administering command climate surveys, a dysfunctional command resilience team and little buy-in department heads on George Washington allowed a poor climate to continue, according to the report. Commanding officer Capt. Brent Gaut asked the command chaplain to set up a subcommittee of the command resilience team to focus on “at-risk” sailors.

The chaplain reported that 50 percent of department heads supported the subcommittee’s requirements, with pushback primarily due to the time it would take.

The suicide prevention coordinator, who is a mandatory member of the command resilience team, did not participate. The inspection report did not say why the suicide prevention coordinator was not involved.

George Washington sailors had not run a crisis response drill since June 2020, despite a Navy requirement for annual drills.

“The former USS George Washington suicide prevention coordinator indicated that drills may have been difficult to execute because he believed suicide prevention was given a lower training priority. From his perspective, the routine occurrence of suicide-related behaviors adequately exercised the crisis response plan,” reads the inspection released Thursday.

The ship’s psychologist, or psych boss, was overwhelmed, a previous inspection into the GW suicides found, USNI News previously reported. GW also had a wait time of 32 days for an initial intake, which was double the average wait time among carriers, the quality of life inspection found.

Overall, the majority of the crew did not trust the mental health care resources on the ship. A common concern among sailors is that if they tell Navy mental health professionals about their concerns, it will negatively affect their careers.

Interior Communications Electrician 3 Natasha Huffman, who was one of the sailors who died by suicide in April of 2022, had complained she did not trust the mental health providers.

In the July 2021 Defense Organizational Climate Survey, sailors reported that they experienced stigma, shame and discouragement for seeking mental health resources. Some junior sailors reported that leaders would not allow time off to receive care.

Of the survey participants, 58 percent said they did not trust military health care providers, with 23 percent saying they did not trust mental health care providers in general.

“I have developed mental issues that I feel I cannot resolve because I KNOW my chain of command does not care and production is what must be pushed every day to the maximum,” reads a statement from a sailor aboard George Washington.

“I feel unsafe asking my leadership for help or even telling them I am going to see the psych boss, or chaplain or whatever because in return they will make me stay late to complete the work I was unable to do when I was at said appointment.”

The data provided in the report gave a snapshot of Navy suicides, usually not seen in the annual Defense Department report. While the DoD report breaks out data by demographics, it does not usually breakdown where the suicides occurred.

The GW investigation reported that a majority of sailors who died by suicide were between 18 and 25 years old, which follows data included in the annual suicide report. In FY 2021, 37.9 percent of suicides were among sailors 20 to 24 years old, with the next highest percentage, 27.6 percent, among those 25 to 29 years old.

The majority of sailors who died by suicide used a personal firearm, according to the data in the report. Master-at-Arms Seaman Recruit Xavier Mitchell-Sandor used a service-issued sidearm to take his life while on duty aboard the carrier.

Caudle and Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy James Honea told reporters that they are aware of the issues with firearms and suicide, with Honea referring to the Independent Review Commission on Suicide, which highlighted a number of recommended changes around firearm use. Caudle and Honea both said the Navy was part of an overall Pentagon effort to mitigate the risk from firearms, but did not give additional details.

Three Hours to Get to Work

A sailor who lived in the Norfolk area and commuted to George Washington might start their day as early as 4 a.m.

A sailor who lived in the Norfolk area and commuted to George Washington might start their day as early as 4 a.m.

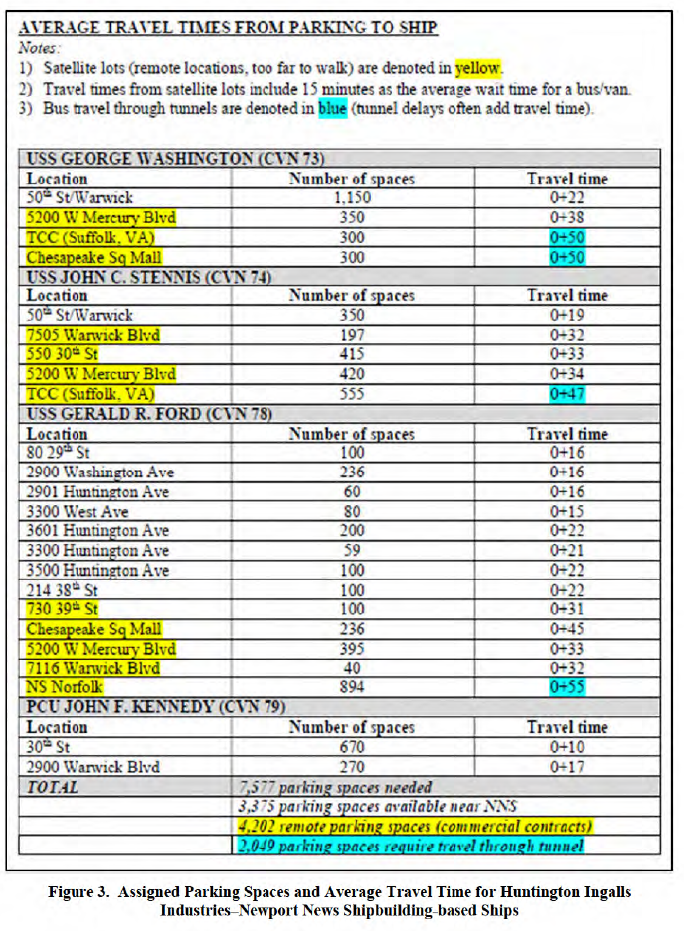

They would get ready for a day at the shipyard, and although they would not muster until 7 a.m., for sailors living away from the shipyard, getting to George Washington could be a three-hour journey.

First, they would drive to an HII parking lot to catch the shuttle bus leaving at 5 a.m. The shuttle, depending on traffic through the Monitor Merrimac Memorial Bridge Tunnel, could get to the dropoff location by 6 a.m.

The sailors then had a 12-minute walk to George Washington, allowing them to get to the ship before their 7 a.m. muster. For female sailors, that 12-minute walk might include a catcall or two from the shipyard workers, according to the report.

That’s the example timeline laid out in the GW inspection. However, depending on traffic a 20-minute drive could become two hours, according to a comment in the inspection.

“Regarding parking further away from the ship, one comment noted, ‘We cannot expect sailors to add an additional bus ride over the bridge each way. The bridges/tunnels back up and a nominal 20-minute drive can become a 2-hour drive. Making Sailors do this would crush morale that is ok at this point but on a thin footing,” reads the report.

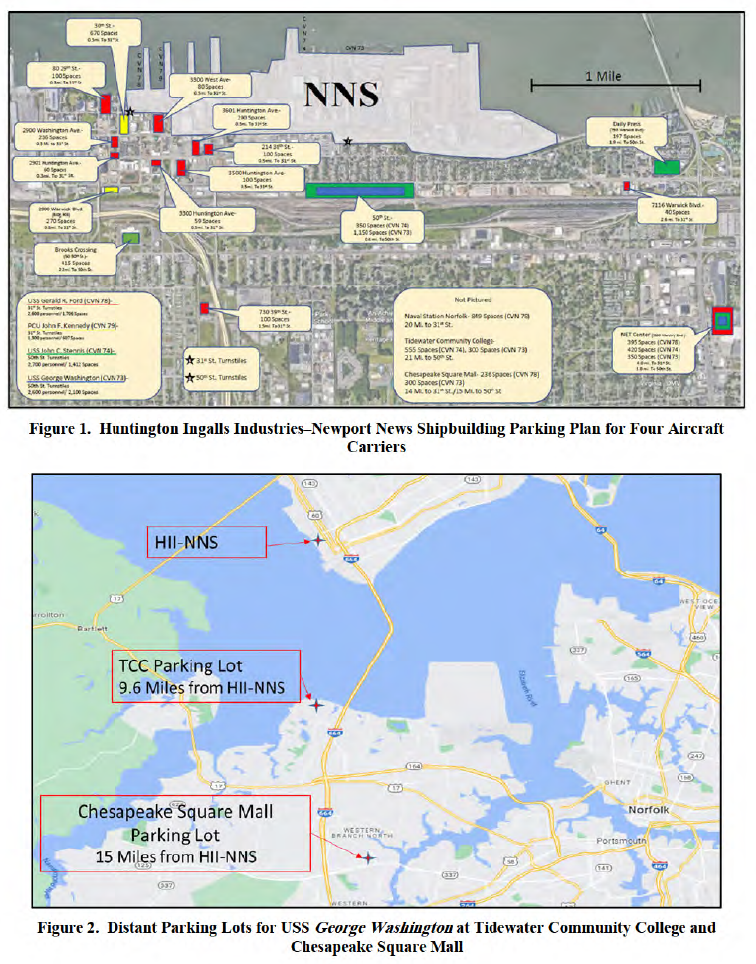

HII provided multiple parking facilities for ships in the shipyard, including four locations in Newport News, Va., one in Suffolk, Va., and one in Chesapeake, Va. Shuttle buses, sometimes driven by Navy personnel, took sailors closer to the ship.

“Sailors joined the Navy ‘to see the world,’ accelerate their lives, or to be ‘forged by the sea,’ but not to see the shipyard or drive a bus,” Meier wrote in his endorsement of the investigation.

However, depending on where a sailor might live from the shipyard, traffic congestion could add up to an hour to a sailor’s commute, according to Dunham’s investigation. Sailors assigned to ships homeported in Norfolk, Va., that were now in RCOH had longer commutes due to traffic. Sailors who moved to the Norfolk area because their ship was in RCOH could choose to live closer to Newport News, but that meant they had less access to services provided at Naval Station Norfolk, according to the investigation.

Sailors voiced concerns over parking, with Dunham writing that the disjointed parking led to sailors feeling as if their commute issues were not a concern for “Big Navy.”

Sailors voiced concerns over parking, with Dunham writing that the disjointed parking led to sailors feeling as if their commute issues were not a concern for “Big Navy.”

Parking concerns were a well-known issue among the ship’s leadership, which took them to AIRLANT. Former executive officers on the ship fought for solutions to the parking challenge, with one former commanding officer highlighting that this was a problem back in 2005 when he served on his first tour.

A former executive officer took the complaints to AIRLANT to no avail.

“I said this was unacceptable but eventually saw the writing on the wall and stopped fighting because the discussion was going nowhere … I believe all RCOH carriers experience the same parking issues. This is a solvable problem and it’s really about money; it’s an issue of the burden we put on Sailors versus the cost we (Navy, HII-NNS and [Supervisor of Shipbuilding, Conversion and Repair, USN, Newport News]) are willing to pay for that parking,” Capt. Michael Nordeen, former executive officer from 2020-2022 said in the report.

After the three deaths in April 2022, the Navy began to address the parking problem, according to the report.

Accommodations

Housing issues for GW sailors stemmed from both living in Huntington Hall and living on the ship.

Huntington Hall is a residence building operated by HII. The Navy pays $4.36 million a year to house sailors there, with each room costing the service about $2,438 per month. For comparison, a 1,068-square-foot apartment in Newport News rents for $1,500 a month on average, according to a May nationwide study from RentCafe.

Of the 149 rooms, 15 go to each submarine in Newport News Shipbuilding, with the remaining used to house aircraft carrier personnel. Sailors at Huntington Hall shared a common bedroom and bathroom with at least two other crew members. Each sailor had about 85 square feet per person.

Per Navy standards, sailors with E-4 ranks in Navy-provided housing should have at minimum a shared unit with a private bedroom, a bathroom shared with one other person and at least 90 square feet per person.

Sailors with ranks E-1 through E-3 should have a shared unit with bathrooms shared between two sailors and a shared bedroom with a minimum of 90 square feet per person.

A Naval Sea Systems Command study in 2010 said Huntington Hall was past “its useful economic life,” according to the inspection.

“Continued use of Huntington Hall is a normalization of deviation,” Dunham wrote as an opinion in the report.

When John C. Stennis arrived for its maintenance period, George Washington sailors were forced out of Huntington Hall and the floating accommodation facility in order to open space up for the other aircraft carrier’s crew.

Sailors who had ranks up to E-4 who are not given basic housing allowance were then moved to George Washington to live aboard in an active construction zone. Ideally, a crew moves back on a ship within six to nine months of redelivery, according to the report.

For the GW crew, the redelivery date kept getting pushed back.

When the last sailors moved out of Huntington Hall, the redelivery date was August 2022. By May 2022, the date had been pushed to January 2023, nearly a year and a half after the last sailors moved out of Huntington. George Washington still has not redelivered, meaning sailors will have lived on the ship for nearly two years.

The Navy required waivers from DoD policy to accommodate sailors from George Washington, reads the investigation.

A former executive officer on the ship told Dunham that the crew move should have been tied to a more realistic date for redelivery.

“He acknowledged that while sailors need to start using the ship’s systems at a certain point, there was a ‘willful blindness to not see we [weren’t] going to meet projected dates or milestones.’ He emphasized that there needs to be an ‘open and honest conversation about RCOH scheduling, [because] the way we do it now is not the best way,’” reads the report.

In addition, most junior sailors assigned to a ship in RCOH have few options to live off the ship. One of the Navy recommendations included a review of basic housing allowance, including evaluating whether the service can provide that option to junior sailors.

“Since 1962, basic allowance for housing/quarters has been restricted to exclude those junior sailors on sea duty,” wrote Meier.

“Where other services provide housing to their junior service members at the installation the Navy is able to rely, in part on ships’ berthing to house our sailors. This berthing, while habitable and designed for an operational environment, is not suitable for supporting a standard of living to which most working-class adults are accustomed.”

When it comes to housing, the Navy raised the question of whether a place was habitable or suitable. While Huntington Hall and George Washington may have been habitable, they were not suitable for the junior sailors, according to the report.

The housing issues were compounded by a lack of resources that sailors would usually have, like a gym, according to the report.

Next Steps

US Navy Photo

Following the investigation, Caudle issued 48 recommendations to improve conditions at Newport News Shipbuilding, including expanding housing options, finding parking closer to the shipyard and improving the food available to sailors.

Among the 48 recommendations are directives to the chief of Naval Personnel to better assess the number of sailors the Navy needs aboard for RCOH, limit first-term sailors to two years on a carrier in RCOH before sending them to sea and providing junior sailors in RCOH a housing allowance to live off of the shipyard.

Caudle also included minimum standards for habitability on a ship, setting a policy that only has sailors on duty stay on the ship or the berthing barge and create a standard for contractor-supplied housing in his recommendations.

While the Navy can make some policy changes now, others will take longer, Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro and Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday wrote in a memo outlining improvements to sailor quality of service, released in conjunction with the report. .

“Navy [quality of service] will not be corrected with the stroke of a pen. Instead, it will require sustained effort that began with the Navy’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 President’s Budget 2024 budget submission,” they wrote.

“To accelerate this effort, we will realign FY 2023 resources, and partner with Congress and the Office of the Secretary of Defense to request additional resources and authorities. These additional resources will be used to accelerate improvements for sailors at Newport News Shipyard, refurbish and modernize facilities, as well as provide the tools and training necessary to build stronger people and healthy unit climates.”

In summing up the improvements, Caudle said making service safe was a major effort going forward.

“This is the time to get after this,” he told reporters on Thursday. “This is an epidemic that’s going through our nation.”

Suicide Prevention Resources

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255)

Military Crisis Line: 1-800-273-8255The Navy Suicide Prevention Handbook is a guide designed to be a reference for policy requirements, program guidance, and educational tools for commands. The handbook is organized to support fundamental command Suicide Prevention Program efforts in Training, Intervention, Response, and Reporting.

The 1 Small ACT Toolkit helps sailors foster a command climate that supports psychological health. The toolkit includes suggestions for assisting sailors in staying mission ready, recognizing warning signs of increased suicide risk in oneself or others, and taking action to promote safety.

The Lifelink Monthly Newsletter provides recommendations for sailors and families, including how to help survivors of suicide loss and to practice self-care.

The Navy Operational Stress Control Blog “NavStress” provides sailors with content promoting stress navigation and suicide prevention.