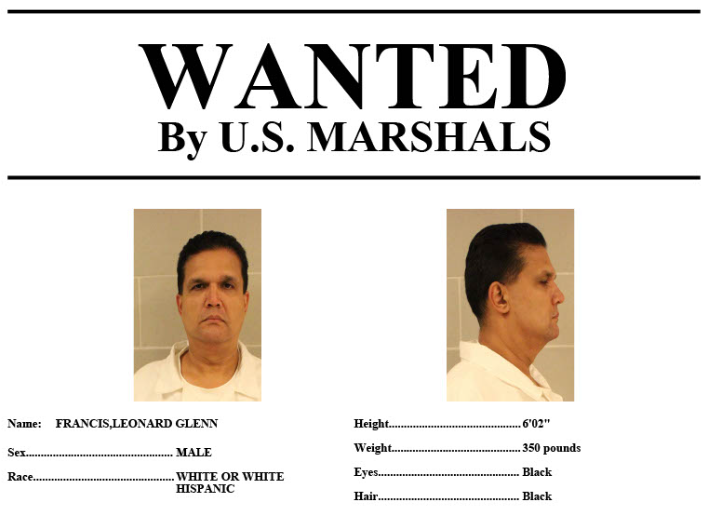

An international manhunt continued Tuesday for Leonard Glenn Francis, a former defense contractor and convicted mastermind of a multimillion-dollar U.S. Navy corruption case who fled custody from home detention Sunday morning, just weeks before he was to be sentenced to federal prison.

Francis, a Malaysian national and the former president of Singapore-based Glenn Defense Marine Asia, was convicted in 2015 after taking a plea deal in exchange for helping U.S. prosecutors implicate three-dozen military officials. Since at least 2018, he has been living in home detention in San Diego under court-approved “medical furloughs” for treatment of renal cancer and other health issues, according to federal court documents. He was scheduled to be sentenced on Sept. 22 before District Court Judge Janis Sammartino.

But at about 7:30 a.m. Sunday, the GPS tracker affixed to Francis’ ankle alerted federal monitors that it “was being tampered with,” a U.S. Marshals Service official told USNI News.

That alert prompted monitors with U.S. Pretrial Services to check on his status, which, per protocols, means ruling out scenarios including a faulty tracker. That agency handles all federal defendants on pretrial or pre-sentencing release.

“They just can’t assume somebody is on the run and call U.S. Marshals,” said Supervisory Deputy U.S. Marshal Omar Castillo, with the U.S. Marshals Service in San Diego. “We got the call from them around 2:30 in the afternoon, and that’s when we went out to the residence.”

About a half hour later, the Marshals’ team arrived at the home, in an expensive area known as Carmel Valley, “to see if in fact he had possibly left or if he just had an issue with the GPS,” Castillo said. When they got there, the deputy marshals confirmed Francis wasn’t there.

Looking through the windows, after announcing their presence, they could see “the house was empty,” he said. Someone found an unlocked door, and “found the GPS monitor inside the house … and the scissors that he used to possibly cut it were right next to the GPS monitor.”

Before the marshals got to the house, San Diego Police Department had been alerted, either by Pretrial Services or Francis’ attorneys, to conduct a welfare check on Francis, Castillo said.

More than seven hours passed between when federal authorities were alerted by the GPS monitor and when marshals arrived at the house. Castillo said he didn’t know what caused the lapse in time. Marshals don’t get involved in any of the monitoring actions “until a judge actually issues a bench warrant for a defendant to be brought back … for pretrial release violation,” he added. It wasn’t clear whether Sammartino issued the warrant. U.S. Pretrial Services provides probation and pretrial work for the federal courts.

Unknown to federal monitors, Francis had been moving belongings out of the property – he lived there with his mother and children, according to court documents – for several days as neighbors told federal authorities they saw several U-Haul trucks “coming in and out of the residence,” Castillo said. “There was more than one” seen on Friday or Saturday.

“We are following leads that have come into our national number, as well as our website, and we are following some leads that we have established ourselves,” he said. “As of now, we think he’s probably going international. It sounds like he’s been planning this for a while.”

Castillo said he didn’t know what security arrangements were in place at Francis’ residence. He understands that Francis had security monitoring him, issued by the court, but paid for by Francis.

“I can tell you nobody was there when we showed up,” he said. “Nobody was there.”

It’s unclear how much time Francis had spent detained in U.S. physical custody before or after his conviction on a guilty plea. He had been living in home detention for at least four years, according to unsealed court documents.

That arrangement, approved by Sammartino with prosecutors’ support, was based on round-the-clock monitoring by a GPS ankle bracelet and a 24-hour-a-day, seven-days-a-week physical guard at Francis’ residence. That residence included a one-bedroom apartment, rented condominium and a gated single-family home, according to court transcripts.

Sammartino, a long-time district judge, has been overseeing the bulk of the cases brought forth from San Diego-based federal prosecutors who have led the long-running, wide-ranging investigation into Francis and GDMA’s alleged fraud and bribery of Navy and military officials, including senior officers serving with the Japan-based U.S. 7th Fleet.

“Our office is supporting the U.S. Marshals Service and its San Diego Fugitive Task Force in their efforts to bring Leonard Francis back into custody,” Kelly Thornton, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of California, said in a statement Tuesday. “We will have no further comment at this time.”

Prosecutors have garnered federal convictions against 33 of 34 U.S. Navy officials, defense contractors and GDMA officers charged in the case, including Francis.

“We can confirm that NCIS is working jointly with the U.S. Marshals Service, Defense Criminal Investigative Service and U.S. Attorney’s Office to locate and apprehend Mr. Francis,” the Navy said in a statement to USNI News. “Out of respect for the investigative process, we cannot comment further at this time.”

Francis’ escape comes just two weeks before he was due to show up in a San Diego courtroom to be sentenced for his role in the case.

Francis was 50 years old when he, along with his company, in 2015 pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit bribery, bribery and conspiracy to defraud the United States, charges that could net him a 25-year prison sentence.

How Francis could escape from a four-years’-long home detention isn’t clear. But court documents unsealed last month reveal that Sammartino, as well as federal prosecutors, had lingering concerns about Francis’ commitment to adhere to judge-approved, pretrial restrictions that would enable him to get medical treatment in San Diego for unspecified ailments. This includes reported Stage 4 renal cancer, according to the transcripts, and other health issues related to aging.

Francis’ defense attorneys repeatedly requested that he be allowed to continue living at home while he received medical care, rather than be medically treated by the U.S. Bureau of Prisons. That request came after he had undergone some medical procedures and was receiving a series of medical treatments that required constant and regular medical monitoring. Those treatments, at times, required adjustments to the private security guards that were required to watch him round-the-clock, including when he moved into a condominium, rented from a medical doctor, for medical care. It wasn’t clear, from available court records, where the security guards were stationed, and how many. During one December 2020 court hearing, his attorney said that two guards alternated 12-hour shifts, a situation that raised concerns when one guard left the property for an extended lunch during a time when a federal pretrial monitor showed up to check on Francis.

“I don’t want to make this more complicated than it is, but in the event that something were to happen and the facility were to be empty one morning and he’s not there and he’s back in Malaysia for whatever reason,” she said, regarding her concerns about setting up that temporary convalescent location.

At one point, Sammartino repeated concerns in court about Francis’ honesty after Pretrial Services told the court that the security guard at Francis’ residence wasn’t on site during one unannounced visit. Francis was paying those security guards. Sammartino ordered all sides to her courtroom, and Francis, speaking by phone, apologized to her and said it wouldn’t happen again.

“Understood,” Francis’ lead attorney, Devin Burstein, replied, according to a transcript.

The judge questioned whether or not the U.S. Marshals Service would monitor Francis, saying that her name was on the the decision to let Francis outside of jail “without any security.”

“You’re not telling me he can’t afford this anymore, because he’s affording everything else, which is infinitely more expensive than the security individual,” Sammartino said.

Sammartino had approved those “medical furlough” requests multiple times, starting at least December 2017 – including in late 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic became more concerning to Francis’ medical condition – and even after she had received, unsolicited, a November 2020 letter from a San Diego-area bariatric surgeon who had been treating Francis that gave him a clean bill of health.

At a hearing to discuss that matter, the judge seemed to question her decision to allow Francis to remain in home detention. Francis had been released, by federal authorities, on his own recognizance and with a GPS bracelet, but without needing to post a monetary bond, as is common in cases where there’s a concern about escape.

“Number one, he could be here,” Sammartino told attorneys at one status hearing. “Number two, what I have traditionally told other defendants in pending cases in this overall conspiracy is that this has been a legitimate medical furlough, and at the point of which it is no longer a legitimate medical furlough, the court may take a different position.

“The other concern I have is, if he is not (redacted), I’m concerned. Is he paying his security team? What is his status? I even went so far as to wonder if he is still in this country. So I would like to hear all of those addressed. And the other thing is, Mr. Burstein, Mr. Pletcher, you have been very diligent in this matter, and it surprises me that I hear this from the doctor directly and not from you when there was a change of [medical] circumstance.”

Francis’ attorney told her that Francis continued to pay his round-the-clock security team and he was living in the house with his children.

“He’s not going anywhere,” said the attorney, who later added that Francis had moved out of the condo, which he had rented from the doctor who he had a falling out with over a billing issue, according to the transcript.

A U.S. Pretrial Services representative told the judge that Francis was monitored, even throughout the times when medical treatments required that the GPS bracelet be removed.

At a status hearing in January 2021, Sammartino questioned the status of Francis’ health and, at one point, raised the possibility of having an independent, third-party medical expert come to the court and explain Francis’ current health and future expectations. He was expected to testify at several pending trials of Navy officials, including five former 7th Fleet officers.

Defense attorneys argued that he would do so in 90-minute increments, with 15-minute breaks to accommodate his medical condition, as was the practice when Francis testified at an earlier military court-martial.

But when that trial began last spring, Francis wasn’t on the witness list. It’s unclear why he wasn’t called to testify. The latest court transcripts available on the publicly accessible website were from a December 2021 status conference, when the judge extended the medical furlough until May 23, 2022.

A federal jury convicted four of the five Navy officers – Capts. David Newland, James Dolan and David Lausman and former Cmdr. Mario Herrera – in late June on charges of accepting bribes from Francis. They are set to be sentenced next month.

The jury couldn’t agree on a verdict for the fifth officer, Rear Adm. Bruce Loveless. Loveless, a former fleet intelligence chief, has continued to contest the charges and is seeking an acquittal. Sammartino has denied his motion for mistrial, and a status hearing is set for Sept. 30 in San Diego.