NAVAL STATION SAN DIEGO, Calif. – While firefighting crews and sailors massed at Naval Base San Diego’s Pier 2 to attack a fire spreading across former USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6), a small fire scorched a mattress on another amphibious assault warship berthed a mile away.

That fire, on a rack in troop berthing aboard Wasp-class USS Essex (LHD-2), was extinguished by a petty officer, leaving the compartment on the ship’s 02 level in a smoky haze.

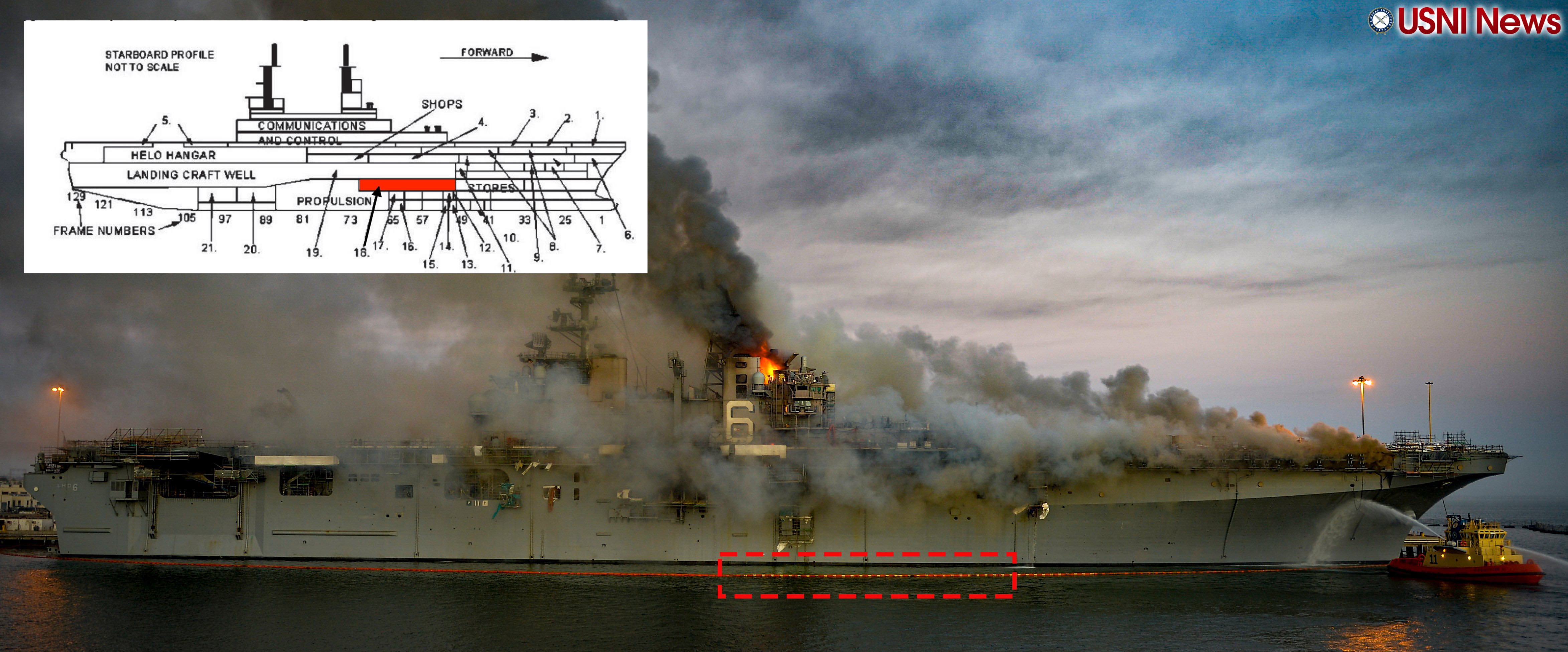

The fire was minor in scale compared to the conflagration that consumed much of the 844-foot-long Bonhomme Richard and its 13 decks. But the mattress fire in COVID-restricted berthing aboard Essex revealed some parallels to the larger fire. A military judge on Wednesday ruled that those similarities are worthy of further examination by defense attorneys representing a junior sailor accused of setting a fire that led to the $3 billion loss of the 22-year-old Bonhomme Richard, which the Navy decommissioned in 2021 and sold for scrap.

Seaman Recruit Ryan Mays, 22, is charged with aggravated arson and hazarding a ship. Mays has denied the allegations, and his attorneys contend that criminal investigators have overlooked other suspects and dismissed potential causes of the fire.

A Naval Criminal Investigation Service probe did not identify any suspects for the July 12, 2020, Essex fire, believed to have been started when someone lit a flammable cleaning wipe found on the charred but flame-resistant bedding.

During a two-day pretrial hearing this week in a courtroom at the 32nd Street naval base, defense attorneys argued that NCIS and federal investigators did not pursue potential links between the two ship fires that occurred the same day at the same base along the same waterfront. They raised the possibility that one person might have set both fires. Investigators do not know what time the fire aboard Essex began, as some time had passed before it was reported that afternoon and the ship secured its brow. A duty fire marshal testified that anyone with a CAC card could access the ship.

While the government determined that the Essex fire was unrelated to the Bonhomme Richard blaze, “that does not mean we are foreclosed from evidence that these two fires were related,” defense attorney Lt. Tayler Haggerty argued before the military judge, Cmdr. Derek Butler.

Prosecutors countered that any connection between the two fires is “sheer speculation,” noting a lead federal fire investigator had identified no link.

Bonhomme Richard “is a massive, incendiary fire,” Lt. C. Jeffers Nyaradi told the court. “The other is a smoldering fire that eventually put itself out or someone put it out.”

Injecting evidence about the Essex fire into the Bonhomme Richard case would create “a trial within a trial,” forcing them to litigate an incident that happened on another ship, she argued.

NCIS Special Agent Alexandra Baruffi, who led the Essex investigation, testified Tuesday that investigators suspected someone unhappy they were stuck in COVID isolation prior to going underway had started the fire, and they looked into several persons of interest.

“Ultimately, no suspect was identified,” Baruffi said, adding that she found no links to the Bonhomme Richard fire.

When questioned by Haggerty, the agent admitted that she had not interviewed the duty fire marshal who doused the smoldering mattress fire.

“There were suspects in the case that the government eliminated for no good reason. They were done with this,” Haggerty argued to the judge. But the fire aboard Essex “poses a relevant alternate theory” in the case of the fire aboard Bonhomme Richard.

Butler agreed, noting the government’s evidence “does not rule out the possibility.”

That two ships had fires on the same day “is a matter relevant to pursue,” the judge said. “The investigation did not identify a prime suspect, leaving the matter ripe. … There’s another

possible perpetrator here.”

“Another possible suspect in the case,” he added, “is not a waste of time.”

Investigators’ Actions Questioned

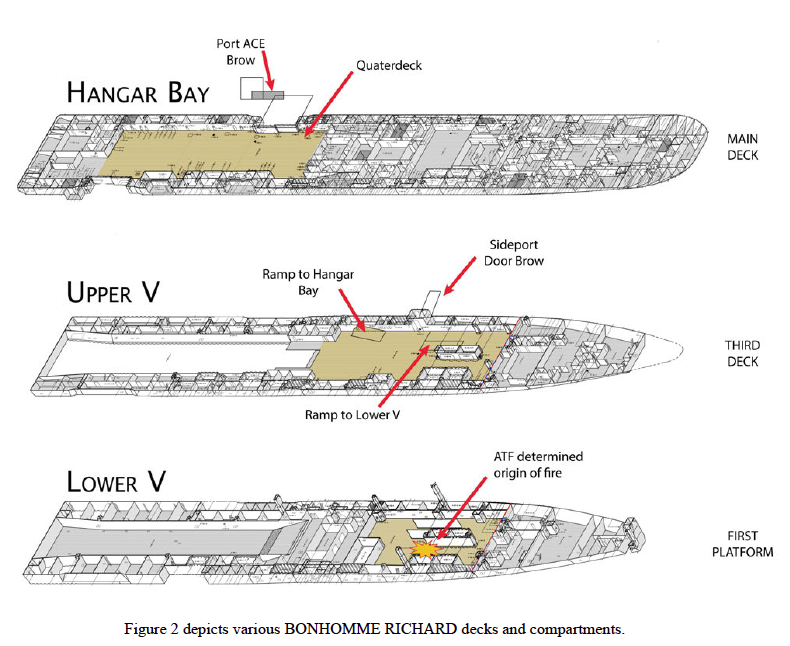

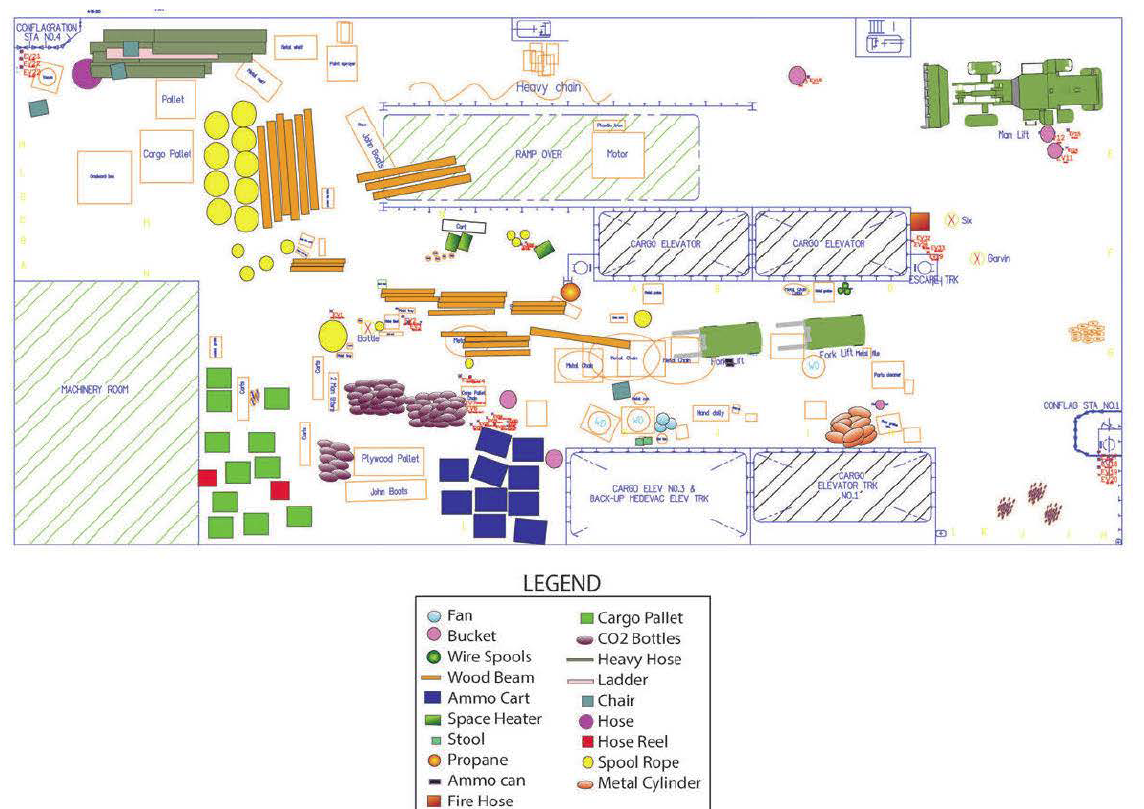

Mays’ attorneys have argued that NCIS agents and a U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives investigator fixated on Mays early on as the suspect in the Bonhomme Richard fire. The Navy’s prosecution against Mays is shaping up as largely based on one eyewitness’ claim of seeing Mays in the ship’s lower vehicle ramp where the fire broke out, an alleged confession overheard by one brig chaser when Mays was detained a month later and what federal investigators said were Mays’ denigrating comments about the “fleet Navy” during nine hours of interrogation by federal investigators that they concluded was motive for arson.

Haggerty said the government readily dismissed sailors suspected in the Bonhomme Richard fire, including Fireman Elijah McGovern, who was spotted in the lower vehicle deck that morning and who investigators learned had Googled “heat scale” before he went home after standing watch. ATF fire investigator Matthew Beals, who identified Mays as the alleged arsonist, testified that McGovern said the search was part of his research for a collaborative fantasy novel with a friend in Texas that involved fire-breathing dragons.

The government didn’t charge McGovern, who left Bonhomme Richard that morning after standing watch, Haggerty said.

Defense attorneys have sought to question McGovern, who last year was separated from the Navy. Lt. Cmdr. Jordi Torres, the lead defense attorney, told the judge that McGovern had lied about his whereabouts the morning of the fire, and his testimony at trial could “cause doubt to Seaman Mays’ culpability.”

Evidence shows that McGovern could be a suspect, Torres told the judge during the hearing.

But it’s unclear at this point whether McGovern will testify or if the prosecution will location him.

“We are actively looking for him to secure him for trial,” Cmdr. Leah O’Brien, a prosecutor, told the judge. “We’re still looking.”

McGovern, originally from Michigan, separated from the Navy on March 3, 2021 as an E-1 Fireman Recruit, according to his Navy biography obtained by USNI News.

Graffiti Confession

The debate over the relevance of the Essex fire was just one of a half-dozen motions the judge considered this week as the Bonhomme Richard arson case marches toward the start of Mays’ general court-martial on Sept. 19.

Defense attorneys sought to quash inclusion of a handwriting expert’s testimony and information about graffiti found on porta-potties at the pier and aboard Bonhomme Richard, including the words,“Ha ha ha I did it. I set fire to the ship.” Another warned: “1 down 3 to go” – a possible reference to the big-deck amphibious ships home ported at the naval base. Graffiti found aboard the ship likely involved soot from the fire.

Prosecutors submitted images of the graffiti and suspects’ handwriting samples to the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory (USACIL) at the Defense Forensic Science Center in Georgia. A forensic document examiner, Thomas Murray, testified by phone that it seemed to be a single writer, and analyses of several sailors’ handwriting pointed to another Bonhomme Richard sailor – not Mays – as a likely source.

A handwriting analysis of graffiti that said “1 down 3 to go” appears to be “taunting law enforcement, Torres said, suggesting that it was McGovern who wrote the graffiti.

Prosecutors argued that such graffiti is hearsay and not legitimate confessions and said McGovern denied starting the fire.

Under O’Brien’s questioning, Murray noted some limitations in analyzing the writing samples and graffiti images he reviewed. The judge hadn’t yet ruled on the graffiti’s admissibility.

Attorneys also argued over Mays’ alleged confession after he was detained at the base for a 10-hour period of questioning by the NCIS and ATF agents in August 2020.

One of the brig chasers, Master at Arms 1st Class Carissa Tubman, testified that she heard a handcuffed Mays mutter, “I’m guilty I guess I did it. It had to be done.”

His attitude, Tubman said, had soured from his earlier more playful and “sarcastic” demeanor as the evening went on, and he complained that he didn’t like working on the ship.

The other two chasers with Tubman did not report hearing Mays’ confession, Torres said. Tubman, in response to a question from the defense attorney, said her hearing is “decent.”

Prosecutors have argued that Mays became resentful at the Navy when he dropped from the Navy SEAL program. He had enlisted with a Navy SEAL contract, but five days into the first phase of the Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL course in Coronado, Calif., which followed several weeks of orientation training, he dropped on request.

Defense attorneys hinted at an ankle sprain that Mays grappled with at the time, and said he hoped to get assigned to another BUD/S class. Why he dropped from BUD/S “is irrelevant,” Haggerty said. But prosecutors and investigators have pointed to his purported disdain for the fleet Navy as the motive for torching his own ship after he failed to become a Navy SEAL.

Work as a deck seaman on the Bonhomme Richard was “beneath him,” said Lt. Shannon Gearhart, another prosecutor. The fact that the junior sailor had to return to living on the ship – it was wrapping up a $249 million shipyard overhaul – had “wore him down.”

Butler, the judge, denied the defense’s request and will allow Tubman’s testimony and statements about Mays’ remarks to be used as evidence in the trial.

Mays, who was assigned to Amphibious Squadron 5 after the fire and demoted to E-1, has not yet decided whether a military jury or just a judge will hear the evidence and decide his fate.