Last summer’s fatal sinking of an amphibious assault vehicle that killed nine has exposed serious shortfalls in unit training and evaluation, command oversight, communication and readiness accountability throughout the chain of command in the Marine Corps and the Navy, an investigation found.

A “confluence of human and mechanical failures” led to the sinking of the AAV, the Marine Corps said in a statement. The service is working on dozens of actions to rewrite and clarify training, operating and safety procedures aimed at preventing a repeat tragedy, and it has taken action against those “whose failures contributed to the mishap.”

Eight Marines and a sailor died in the July 30 sinking in the Marine Corps’ deadliest amtrac mishap at sea. After water began to seep into the amtrac a mile off California’s San Clemente Island, nearly 45 minutes passed before the vehicle commander ordered the 13 passengers to evacuate. But by the time another amtrac reached it and maneuvered to help, it was too late, and the 26-ton vehicle sank before everyone had exited.

The mishap’s cause “was a combination of maintenance failures due to disregard of maintenance procedures, AAV crewmen not evacuating personnel when the situation demanded for such actions, and improper training of embarked personnel on AAV safety procedures,” the service said in the March 25 statement announcing completion of the 2,000-page command investigation into the mishap. The Marine Corps publicly released a redacted copy totaling 1,723 pages, but officials made no other public statement about the investigation.

The mishap took the lives of Navy Hospitalman Christopher Gnem, 22, of Stockton, Calif., and eight Marines: Cpls. Wesley Rodd, 23, of Harris, Texas, and Cesar Villanueva, 21, of Riverside, Calif.; Lance Cpls. Marco Barranco, 21, of Montebello, Calif., Guillermo Perez, 19, of New Braunfels, Texas, and Chase Sweetwood, 19, of Portland, Ore.; and Pfcs. Bryan Baltierra, 19, of Corona, Calif., Evan Bath, 19, of Oak Creek, Wisc., and Jack Ryan Ostrovsky, 21, of Bend, Ore.

The top investigator, along with the I Marine Expeditionary Force and Marine Forces Pacific commanders, determined the failures and missteps led to deaths they found were ultimately preventable.

The long list of contributing factors included an absence of Marine Corps or Navy safety boats during the training event and the platoon receiving “deadlined” vehicles – AAVs that were set aside and in poor material condition. Marines lacked training and did not follow standard procedures, had inefficient flotation vests, and were operating in high seas – factors that raise serious questions about accountability at various units and senior commands, the investigation found.

The mishap happened during the first joint, at-sea training period for the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit and the Makin Island Amphibious Ready Group, called The Amphibious Squadron Marine Expeditionary Unit Integration Training exercise (PMINT), and on a day when the integrated, blue-green unit and ships were handling multiple training events at San Clemente Island and in Southern California.

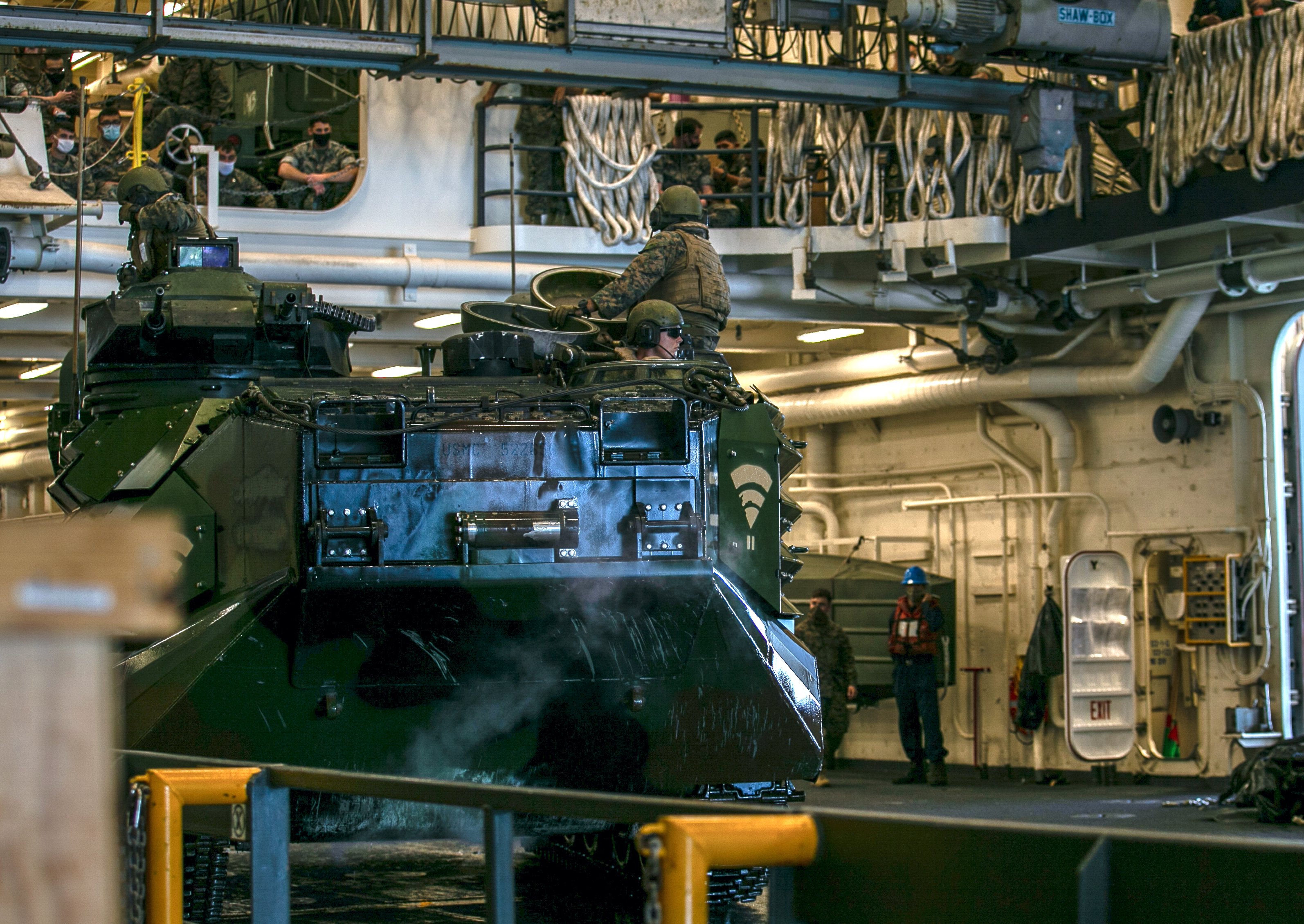

The vehicle and AAV crew were sourced from 3rd Assault Amphibian Battalion platoons at Camp Pendleton, part of the 1st Marine Division, and had landed on San Clemente Island after leaving amphibious transport dock Somerset (LPD-25). The passengers belonged to Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Marine, the battalion landing team for the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit, and had embarked for the return trip to Somerset. Somerset, USS Makin Island (LHD-8) and USS San Diego (LPD-22) are all part of Amphibious Squadron 3.

The investigators were troubled by assumptions made by Marine Corps and Navy personnel about who was providing safety boats for the AAV waterborne mission and poor communications between the AAV unit and the ships when the vehicles were off Somerset, according to the investigation.

Moreover, the accident happened during an amphibious mechanized raid, a normal MEU training event and a mission-critical to the future of the Marine Corps. It’s a crucial capability particularly in the island-hopping operations envisioned in the Indo-Pacific that rely heavily on integrated support from the Navy.

“We have to be good at this. This is our core competency, amphibious operations,” said a former MEU commander who was briefed on the investigation. “This is the way we’re going forward to fight as part of the joint force with our Navy counterparts in the littorals coming from the sea. So we have to get good at this, and we will.”

“We often say what we do is a dangerous business, and it becomes more dangerous when you don’t follow directed procedures or standard operating procedures and approved [tactics, techniques and procedures] that are designed and trained to make you more effective,” said a former division commander familiar with the details of the investigation. In this case, “throughout that chain, there were things that went wrong, and that’s why so many people are being held accountable.”

Actions in the aftermath

The day after the mishap, the commandant, Gen. David Berger, suspended all AAV waterborne operations until the Marine Corps completes a comprehensive review of equipment, procedures and training pertaining to safety during all waterborne operations. The Marine Corps also ordered fleet-wide inspections “of every AAV with new criteria for hull water-tight integrity, bilge pump function and emergency egress lighting systems,” the service announced. The Marine Corps Training and Education Command held a course curriculum review board for the Underwater Egress Training program, which includes three types of trainers to allow Marines and sailors to get familiar with water scenarios and learn how to escape from vehicles or aircraft if needed.

Two senior commanders – Col. Christopher Bronzi, who led the 15th MEU, and Lt. Col. Michael Regner, who led BLT 1/4 – were relieved of command, along with 1/4 Bravo Company’s commander, by the I MEF commander, Lt. Gen. Karsten Heckl. Heckl also “has taken appropriate administrative or disciplinary action against seven other personnel whose failures contributed to the mishap,” the service announced without offering details.

Lt. Gen. Steven Rudder, who commands the Hawaii-based Marine Corps Forces, Pacific, provided the investigation to the TECOM commander, Lt. Gen. Lewis Craparotta, “recommending appropriate administrative or disciplinary actions to address failures by the former commander of 3rd AA Battalion,” Lt. Col. Keith Brenize, who led the unit at the time the AAV Platoon formed and received the vehicles ahead of joining the 15th MEU and is currently attending top-level school at Quantico.

“People had [a] responsibility to do things a certain way. The mechanical failures did not cause the loss of life. This vehicle sank over a period of 45 minutes,” said the former MEU commander, who spoke on background to discuss the investigation’s findings and the service’s follow-on actions. “There were multiple opportunities to intervene and prevent the loss of life. That’s the sad story behind this mishap and this tragedy.”

Other actions are underway

The Marine Corps is taking a deep dive into four Marine Corps orders that govern MEU operations and the preparation of its subordinate units: Marine Corps Force Generation Process Order; Marine Corps Combat Readiness Evaluation; MEUs Policy; and MEU Pre-deployment Training Plan. The orders are being reviewed “and will be rewritten with the lens of safety and the command investigation as how we review those, to tighten those up and make sure we learn from this accident and we don’t repeat some of the same mistakes,” said a former division commander who has led a MEU BLT.

“We are going to be more directive,” he added. “Some things become non-waiverable.”

Some 52 separate recommendations are working their way through the Marine Corps and, for some, with the Navy, the senior official said.

Rudder also has asked the Marine Corps to review UET training and procedures, the effectiveness of the LPU-41 flotation device and, in coordination with the Navy, the Common Standard Operating Procedures for Assault Amphibian Operations “and develop it into an applicable directive,” the Marine Corps announced. He wants a review of the Amphibious Combat Vehicle program – the AAV’s replacement – “to ensure lessons learned from AAV mishaps are incorporated into training, operations and maintenance when the ACV is fielded, and current ACV safety features adequately support emergency egress.”

He’s also asked for “continued sustained funding of the AAV program for as long as the vehicle is in service,” and for standardization of water integrity testing procedures.

In addition, Rudder directed I MEF and Japan-based III MEF to review all safety procedures and practices with waterborne operations, “ensure commanders are directly responsible for safety structure, and require general or flag officer notification prior to use of AAVs as safety boats.”

He ordered the MEFs to clarify guidance on supplying MEUs with trained personnel and equipment that’s ready, ensure units conducting AAV water operations are trained and evaluated during pre-deployment workup periods and ensure personnel receive appropriate rest prior to doing high-risk training and operations. He also required that all AAV and mechanized unit leaders review a well-received Naval Postgraduate School study of AAV emergency exit, in addition to mandating the MEFs ensure positive communications between AAV leaders and ship personnel and ensure appropriate ship personnel grant permission to launch AAVs to or from a ship.

“We’re a learning organization. We’re going to capture what we learn about this tragedy,” said the former MEU commander. He noted the 1999 fatal sinking of a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter, which fell into the Pacific and sunk while trying to land on the oiler USNS Pecos (TAO-197), as the service’s “impetus” to require underwater egress training for Marines embarked for conducting helicopter operations. “It’s saved lives,” he said. “We can learn from this mishap and apply things that’ll save future lives.”

“We’re going to have to trust that the Marines and their counterpart sailors know what the standards are, are enforcing the standards and are trained to those standards,” he added. “We have some work to do going forward.”

Helping manage risks

One safety official described the investigation’s overall findings as “not what right looks like, on the most basic level.”

“The failures go well beyond just the specific incident, the specific vehicle, but in fact extend back all the way through the training plans associated with preparing this unit to conduct this exercise,” the official said, speaking on background to explain what the investigation found and what actions the Marine Corps is taking. “How is the Marine Corps looking at the larger problem of managing risk? There are significantly better ways to do that exact thing.”

Already, Marines are starting to get new tools to help. One is a safety management system, similar to what’s used by the FAA and the Air Force, that was fielded in October for aviation and ground units “to help commanders as they begin to figure out how to train and then employ the unit,” the safety official said. “The management of risk needs to be continuous.”

“We cannot relax and go into an administrative mindset and wind up not accounting for a situation where significant hazards are starting to accumulate,” he added.

Another is the Risk Management Information tool, which streamlines incident reporting and makes it easier to share information and lessons learned.

“It’s based on a very successful Air Force system,” the safety official said. The Marine Corps also is looking at other safety reporting tools, including one that might enable a Marine to report “anonymously hazards they’re seeing so safety officers and commanders can take action to mitigate identified hazards and associated risks.” It also has established a Marine Corps Mishap Library that’s “readily accessible” to junior leaders, he said. One goal is to seamlessly link a mishap to the associated training events and course syllabus so Marines “can better understand” what happened.

Four key failures

As the mechanized company for the 15th MEU, Bravo Company’s Marines and sailors piled into 13 working amtracs of its AAV Platoon in the predawn hours aboard Somerset, which they boarded a few days earlier at San Diego Naval Base for two weeks of training at sea. They had their typical kit of gear, including packs, helmets, Kevlar vests with ballistic plates and rifles. Some – but not all, as the investigation found – wore LPU-41 flotation vests provided by AAV crewmen.

Upon reaching San Clemente Island, they moved inland to the objective, a mock enemy site where they fought against role-playing enemy forces. They returned to the island’s West Cove for the AAV ride back to the ship. But one amtrac suffered a broken hub, and the company command decided to stay back with three other AAVs overnight until a repair could be done. Not long after the nine remaining amtracs launched, one of the AAVs had malfunctions that required it to be towed by another AAV back to the island.

Among the seven pushing toward Somerset was AAVP7 SN 523519, with a crew of three and 13 passengers, including some Marines who hadn’t been aboard the AAV for the initial swim to San Clemente. It wasn’t long before it was trailing the others, four of which made it to Somerset before realizing that the AAV was in serious trouble.

There began a series of failures in four key areas: maintenance and mechanical, failure to timely evacuate, inadequate training and inadequate safety measures, officials said.

The emergency egress lighting system was disabled, an oversight by the crew, leaving the Bravo Company passengers in the dark. The AAV had a transmission oil leak that went undetected, even after a crewman added six gallons of oil while on San Clemente Island. The loss “should have been kind of a tipper; that’s pretty significant and it’s not normal,” the former MEU commander noted. “But the crew did not report that, and they splashed anyway.”

Water leaked through doors and other areas including gaps in headlight and plenum seals, and in the engine compartment. The vehicle lost propulsion as the engine began to slow, then the generator began to fail and two of the four bilge pumps stopped working. “We’ve got a series of mechanical failures that are compounding the danger this AAV is in,” he said. “It becomes what we call a slowly sinking AAV.”

When the crew first saw water at deck plate level, they should have begun plans to possibly evacuate, per the standard operating procedure. But that didn’t happen, even as the water rose to boot-top level and then reaching the benches in the troop compartment. The passengers weren’t properly briefed on what to do in such an emergency, and even were confused on how to open a top hatch to escape.

The unit was inadequately trained, the investigation found, so the Marines and sailor in the back of this amtrac weren’t familiar with what to do when it started taking on water. They lacked the requisite familiarity and “the comfort to appropriately react in emergency,” the former MEU commander said. In fact, while the AAV platoon had done a handful of beachside swims in their vehicles, the amphibious raid was the first time Bravo went to sea in the amtracs.

“Training failures led to failure to follow SOP,” he added. “The vehicle crew, in totality, did not follow the SOP.”

The AAV platoon hadn’t received all the required training before joining the 15th MEU in April 2020. Most notable was the Marine Corps Combat Readiness Evaluation “that was supposed to have been conducted, for either the platoon or the platoon as part of a larger organization, [but] had not been conducted,” the officer said. “If so done to standard, the AAV platoon would have operated with an amphibious ship and would have been able to work some of these procedural issues out and had more familiarity with it. They did not complete that training to standard, and they did not have an opportunity to operate with an amphibious ship prior to this at-sea period in July.”

‘Not Good Alternatives’

The amphibious raid mission had an inadequate safety structure in place that day. There was no Marine Corps or Navy safety boat in the water, as required, and the AAV Marines’ plan for an empty amtrac to fill in fell apart once the mission began.

“People made assumptions about what each was doing,” the former MEU commander said. The confirmation briefing held the night before noted that Somerset would provide a boat. “The ship assumed the AAVs were doing it, as it was done in the morning [going to the island]. The AAVs assumed the ship was doing it, as in confirmation brief,” he said. “That’s a shortfall in safety procedures.”

The lack of a safety boat may have also led to the delayed decision to evacuate.

“The vehicle commander had a tough choice to make,” said the former MEU commander. “There was no safety boat immediately available to put the Marines and sailor in his charge into for a transfer. For a long time, he was by himself, as the last vehicle in a column of vehicles with a ship somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 yards away and no other vehicle or safety boat anywhere in proximity.”

The Marine waved the distress flag for 20 minutes and kept trying to radio higher headquarters, but his message kept getting cut off. “He had a lot going on… but he waited too long to decide. There were not good alternatives,” the former MEU commander noted, and “he [had] not fully understood the distress that the vehicle was in.”

The Marine hadn’t yet been to formal schools training for his billet and didn’t fully comprehend what to do as the water rose higher, he said, so the choice was to get the amtrac back to the ship “or put them into the open ocean where there was no immediate safety boat.”

Disparities in directives

Safety boats are required whenever doing AAV waterborne missions, with one safety boat – such as a rigid-hull inflatable boat or combat rubber raiding craft – required for five or fewer amtracs and two safety boats for six or more, officials said.

While the commanders’ pre-mission confirmation brief determined that “Somerset would provide a safety boat” for the roundtrip mission, the former MEU commander said, the “investigation finds that plan was changed within the lifelines of the Somerset in consultation with [the] ship’s company and the AAV platoon. The investigation also notes that there is some disparity in the governing directives, which creates a degree of ambiguity.”

“The Navy governing directives say that the ship would provide safety boats, unless the AAV unit does. The AAV governing directives say the ship will provide safety boats, but they’re not really required for AAV operations, because the AAV unit can do it,” he said. “Both sides of that chain of command made incorrect assumptions about what the other side was doing, particularly on the way back out” returning to the ship.

Once a mission plan is confirmed, the plan “doesn’t get changed without the changes being re-briefed” unless it already was approved, he said. The investigation also found communications confusion between the ship, BLT 1/4 and the AAV platoon.

One issue arose over Bravo and the AAV platoon’s decision to splash and return to Somerset. The disabled AAV left on San Clemente delayed the mission by more than four hours, but the ship had other missions on schedule, including flight and refuel operations that conflicted with well deck operations.

“There was no aft lookout stationed on the back…where he or she might have seen the amtracs in the water swimming back to the ship,” the former MEU commander noted. It’s unclear who on the ship approved the amtracs’ return. There also was confusion about the mishap AAV’s status as it was taking on water because of the other broken AAV that was getting towed back to the island.

The Marine Corps isn’t doing open-water operations without actual safety boats in place, officials said.

“What we’re going to do is bring this topic up at the Naval Board, and then jointly look at our directives,” said the former division commander. The Marine Corps will review with the Navy its Wet Well Operations manual and other directives on ship-to-shore, ship-to-ship movement and look for any incongruities or “make that language more directive.” There’s no timeline set, he said, “but it will be sooner than later.”

The Marine Corps, years ago, divested of its boat lockers that had made available small boats to division units. “We’re going to probably rectify that with a Program of Record, where we would purchase boats and capability in the future, so we can have that more resident in not only Reconnaissance battalions but probably in the AAV battalion as well,” he said.