The Navy is moving into the next phase of a wholesale revision of its ship maintenance infrastructure. Last week, the service announced it had started to digitally map the layout of its centuries-old Norfolk Naval Shipyard as it seeks to bring new technology and a more efficient workflow to the public yards.

While service officials have pointed to the Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Plan (SIOP) as a way the Navy is pushing for modernization and efficiency in its yards and facilities to enhance throughput and readiness, some lawmakers have voiced concerns about the plan’s timeline.

As the Navy continues work on the SIOP, it has now started the modeling needed to produce a digital clone of the Virginia yard, according to a service news release. The Navy previously conducted a pilot program for modeling at Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility to assess various yard layouts and simulate potential designs.

“With these digital models, we can set the stage for NNSY and the other public shipyards to become a smarter and more predictive shipyard. We can track the flow of the shipyard and see where we need to make adjustments, especially on the waterfront where the workforce works each and every day to maintain our nation’s assets,” Steve Lagana, the Navy’s program manager for SIOP, said in a statement.

“For example, at Pearl Harbor we tracked a valve going from shop to shop for repair. At its current layout, the valve bounced around from place to place and it was overall not set up for success,” he added. “With this digital model, we can simulate new ways to layout our shipyards to help save man-days and decrease duration – and overall make our shipyards more efficient and modernized.”

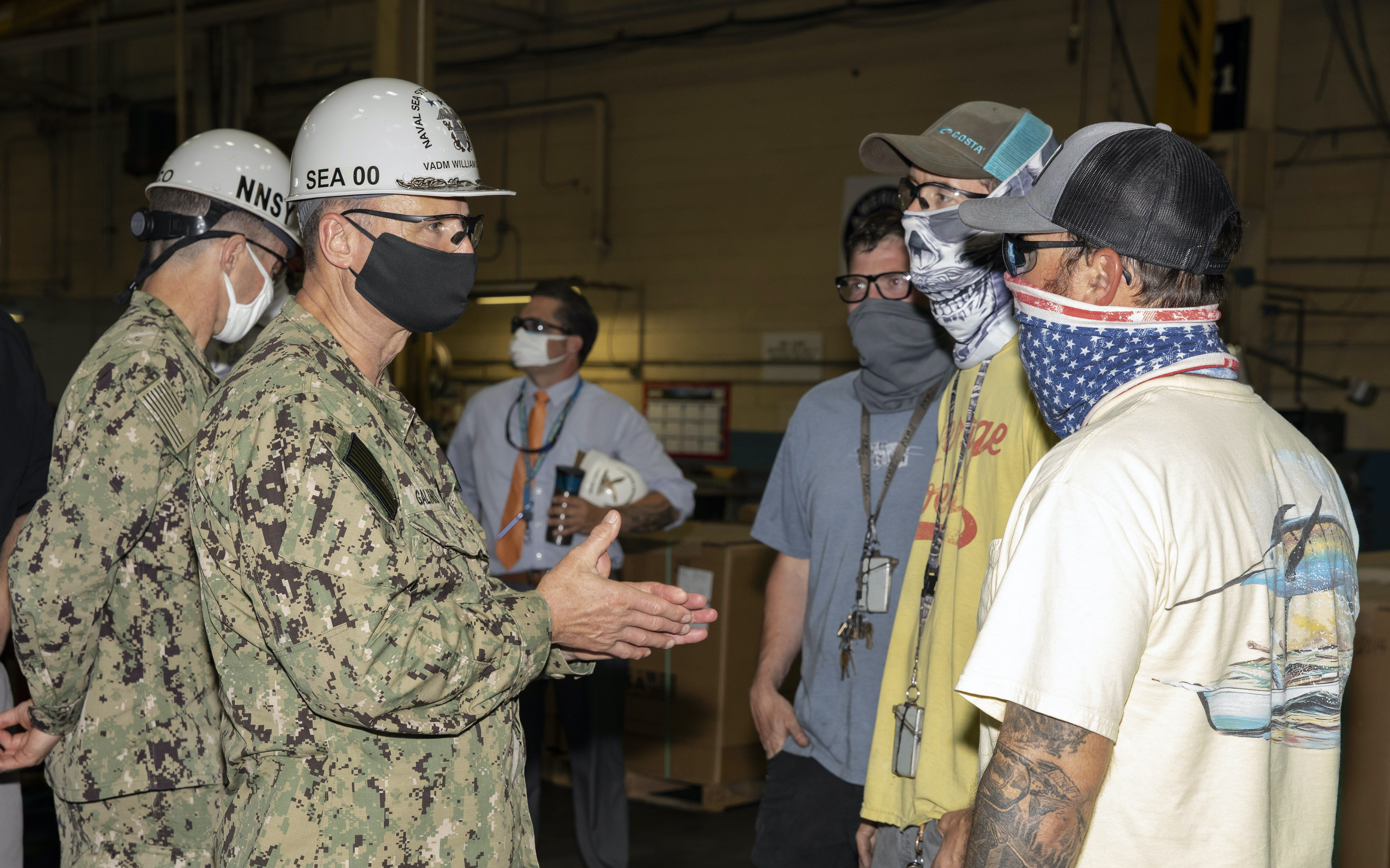

While the Navy has struggled with performing on-time ship maintenance over the years, Naval Sea Systems Commander Vice Adm. Bill Galinis recently told USNI News that the service is working to burn down the number of days it loses to maintenance delays, going from losing 7,000 days in Fiscal Year 2019 to 1,100 in FY 2020.

The Navy expects the SIOP to cost $21 billion over the next 20 years across its four public shipyards. Though service officials have pointed to incremental work like modeling the yards as examples of success, some members of Congress have suggested the Navy’s approach could face challenges.

Rep. Rob Wittman (R-Va.), the ranking member of the House Armed Services seapower and projection forces subcommittee, believes the Navy’s 20-year timeline for the SIOP program is too lengthy to effectively improve the yards and that the plan fails to factor in the modernization needed for future platforms, like unmanned systems, that will enter the fleet.

“I just don’t think that you have 20 years in order to recapitalize these shipyards because things are going to change,” Wittman told USNI News in a recent interview. “Think about it – in the meantime, as you’re doing this, you’re going to have new lightly manned and unmanned systems coming onboard, so you’re going to have a lot of modernization in the fleet and you’re going to take 20 years to modernize your ship maintenance yards?”

Wittman pointed to the dated facilities and machinery in Norfolk that make it hard to recruit and retain employees, as well as an ineffective yard layout, as items the service needs to fix in its yard improvement effort.

“If you walk into these shipyards and you look at the machine shops, if you look at the buildings, if you look at the things that are in there, you feel like you’ve walked into World War II shipyards because they’re old. The floors are cracking. They’re old steel buildings. They’re not climate controlled. The machining systems in there are old. These are not modern workplaces,” Wittman said.

“And because of that, that translates over to the workforce. Now you have problems with workforce because you don’t have the proper number of people, so when you don’t have the proper number of people and you try to get this work out – and by the way they’re not even successful with that, only 75 percent of the work is getting out of the yard on time, and the reason is is because they just don’t have shipyard workers,” he continued. “And they’re now taking the shipyard workers they have and working massive amounts of overtime, which just burns out the workers that you have, so you further exacerbate the problem.”

When first launching the SIOP efforts in 2018, former Naval Sea Systems Command chief Vice Adm. Thomas Moore cited the yard layout, in addition to flooding problems at the dry docks, as objectives the service hoped to rectify at Norfolk with the infrastructure modernization push.

The latest work in Norfolk on the SIOP comes as Defense Secretary Mark Esper has called for an increased shipbuilding budget so the Navy can build a fleet of more than 500 ships that would include both manned and unmanned platforms. The effort – dubbed Battle Force 2045 – specifically calls on the service to grow its number of attack submarines from the current 66-submarine goal to 70 to 80 SSNs, and to construct three Virginia-class boats each year.

Esper, in previewing his plans for the Navy, said the service would refuel seven Los Angeles-class submarines, an increase from the five to six boats the Navy considered refueling. This refueling work is typically performed in the public shipyards.

Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.), who chairs the seapower panel, told USNI News the Pentagon’s focus on building up the submarine fleet is long overdue but that it would take time for the Navy to grow its number of attack boats.

“There at least now seems to be no debate about whether that’s a place the country has to invest in more,” Courtney said of submarines. “How you do that – I mean, you need to do a lot more [facilitation] if you’re going to get above 66 [attack submarines] in any time in the near future. And you’re probably going to have to do some service life extensions for the Los Angeles-class subs, which that takes you right back to the public shipyards because that’s where all that work gets done.”

Wittman praised Esper for his focus on shipbuilding and growing the fleet but argued an increased number of ships means the Navy will need additional funding for maintenance and military construction.

“To me that’s the great segue to say, ‘Well if we’re going to increase shipbuilding, we ought to increase not only the ship maintenance budget — which is the nuts and bolts of getting ships maintained — but also the infrastructure and capital budgets on the [military construction] side to make sure the capacity’s there,’” he said. “Because you can devote all kinds of money to repairing ships, but if your yards don’t have the capacity to do that, you’re going to find yourself again stacked up in the yards.”

Wittman pointed to USS Boise (SSN-764), a Los Angeles-class submarine that couldn’t dive for years because it was waiting for a maintenance availability, as an example of the logjam that can happen at the yards. Boise moved to Newport News Shipbuilding’s dry dock in Virginia earlier this year after waiting several years for an availability at Norfolk.

“You cannot have ships that are available to go to sea on deployment if you can’t maintain them. And you see just an accordion effect where one maintenance availability backs up and then another, and then another, and then another,” Wittman said.

Courtney said that, while any blueprint for modernizing the yards is a step in the right direction, he believes Wittman’s suggestion that the SIOP does not go far enough is “totally legitimate.”

“Because again, the horror stories of repairs and availability delays is … responsible for [the] lack of deployments and … demand signal that’s coming out from places,” Courtney said. “I mean, the horror stories, particularly … [the] Los Angeles-class submarines and Seawolf-class submarines, are just really embarrassing.”

Meanwhile, the Heritage Foundation in a recent report expressed concern that the SIOP only takes the size and composition of today’s fleet into consideration and does not factor in future needs. Since Heritage released its report, Esper rolled out his plan to grow the Navy to more than 500 ships based on a new fleet architecture, but there has not been an accompanying plan outlining how the Navy and its public and private shipyards would maintain that larger fleet.

“Ultimately, the SIOP should to be considered in light of what it is: a plan to make the four current Navy shipyards effective in meeting the needs of the current fleet as outlined in the 2016 force structure assessment. It does this in a robust, technologically advanced, and forward-thinking way,” the report reads. “But Navy leadership also needs to think critically about the future of Navy shipyards in light of a potentially changing Navy force structure as the U.S. returns to an era of great-power competition.”

In addition to Norfolk, the SIOP is slated to revamp Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility in Hawaii, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Maine and Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and IMF in Washington.

While Congress has yet to unveil the final version of the FY 2021 defense policy bill, lawmakers during the markup process took steps aimed at implementing oversight of the Navy’s SIOP efforts.

The House Armed Services readiness subcommittee included a provision in its mark mandating the Navy secretary give the defense panels a briefing twice per year on SIOP from mid-2020 through mid-2025.

The provision calls on the secretary to speak to a variety of topics, like a line item for the SIOP in the future years defense program, a blueprint for how the Navy plans to improve its infrastructure and military construction projects, and an evaluation strategy and metrics for execution. The updates should also feature “a workload management plan that includes synchronization requirements for each shipyard and ship class,” according to text of the subcommittee’s mark.

Wittman pointed to the Navy’s modeling work and predictive maintenance as a way the service can plan for and improve executing availabilities on time. He said he has worked closely with Navy acquisition chief James Geurts to ensure the service is taking advantage of the data it can obtain from ships.

“On the maintenance side, I think if they will advocate an increase [in the military construction] budget and an increase in the ship maintenance budget to make sure that we address these backlogs – and I know within [the] Navy they’re looking at doing everything they can to make the maintenance framework more efficient,” Wittman said.

“And where [the] Navy has to do a better job is they have to do a better job on the planning side, because we still see delays when they bring a ship into the yard and they unzip it and they look at it and say, ‘Well, guys, we didn’t expect to have to replace this valve but we have to replace it,'” he added. “Or they open up a tank and they go, ‘Wow, there’s more corrosion in this tank than what we thought there was.’ So they have to do better.”