CAMP PENDLETON, Calif. – Marines and sailors deployed over the weekend to the frontlines of multi-agency firefighting efforts on the Creek fire, which has consumed more than 122 square miles in central California.

The Marines and sailors assigned to 7th Engineer Support Battalion – about 250 personnel in all, including about a dozen Navy hospital corpsmen – will form as hand crews with strike teams, each led by a wildland firefighter, for a deployment of unknown length. They will join more than 3,100 personnel fighting the Creek fire, which sparked Sept. 4 and has scorched 278,368 acres of mostly forested land. The fire was only 27-percent contained as of Monday morning, according to fire officials.

The deployment is the latest assignment of West Coast-based I Marine Expeditionary Force units to assist federal and state firefighters battling dozens of blazes that were burning across California and the West. These fires, which have already produced some harrowing search and rescue efforts – such as one at the Mammoth Pool Reservoir in the Sierra National Forest northeast of Fresno – have come before the California fire season typically starts, leading to worries about the ability to fight such a long season and rotate in and out qualified crews to help state and federal firefighting efforts.

Marines Conduct Final Training Ahead of Deployment

Earlier this month, crash-fire-rescue teams with Marine Wing Support Squadron 373 deployed to support the aerial firefighting mission on the Slink fire, which spread onto training areas of the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center in the Eastern Sierra mountains. Lightning sparked the fire Aug. 29, and it has since burned 26,752 acre but is expected to be fully contained by Sept. 26.

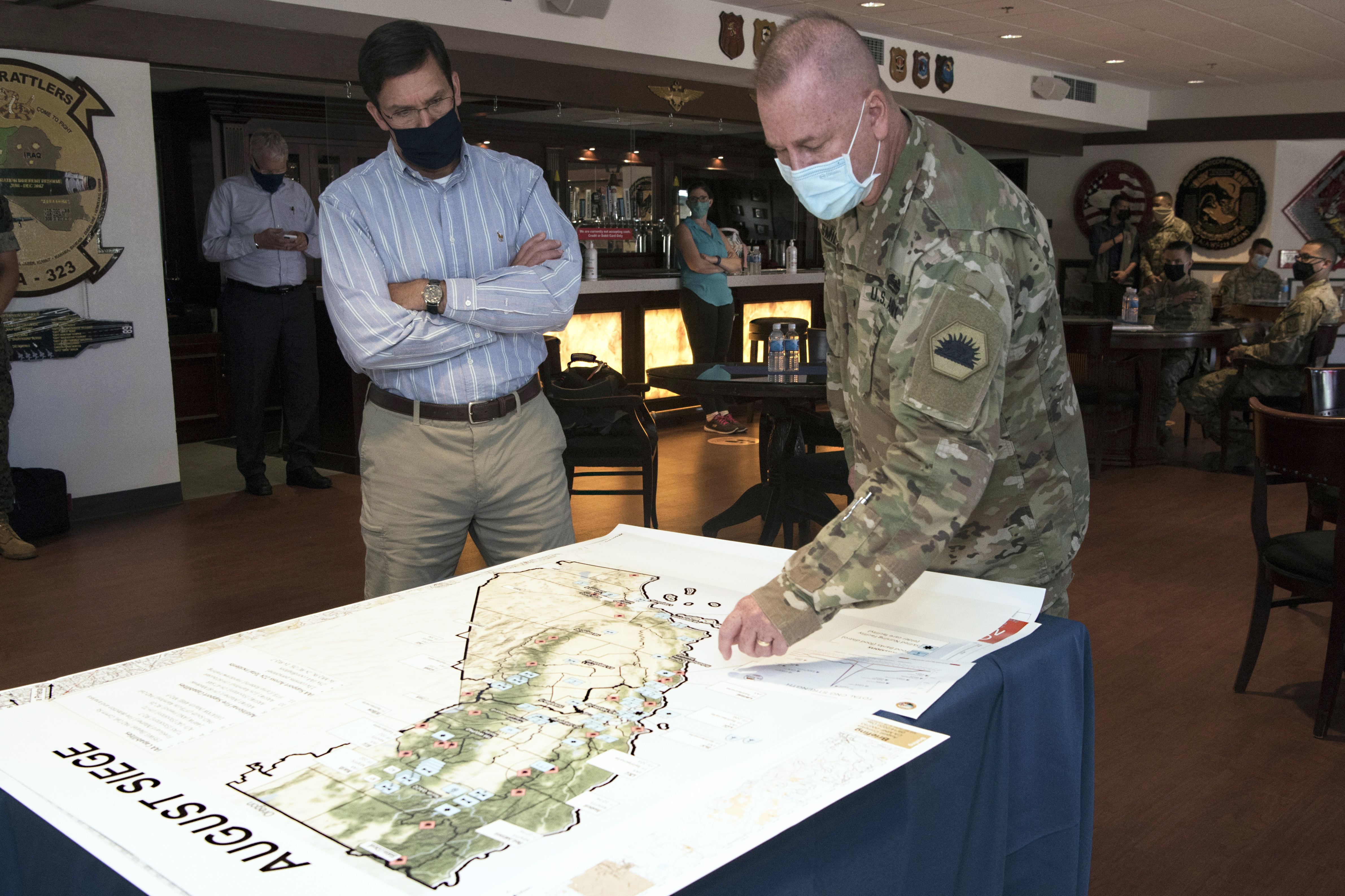

U.S. Northern Command last month tasked U.S. Army North with overseeing military support to the ground response in support of the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) in Boise, Idaho, which serves as the federal coordinator for wildland fire missions. Two Army battalions typically are tasked to support if needed. Recently, ARNORTH deployed soldiers with 14th Brigade Engineer Battalion, 2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, from Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash., to the August Complex fire burning in Mendocino National Forest in Northern California.

The Marines’ 7th Engineer Support Battalion got word a week ago that it was getting tasked to help wildland firefighters.

“We’ve been preparing for a few weeks now with the possibility of having to support this mission,” Lt. Col. Melina Mesta, who commands the 1,300-member battalion, said during a Friday media briefing.

“We had more folks volunteer than spots available,” she added.

Mesta said some battalion members have relatives in the area, which includes the city of Fresno, “so it definitely hits close to home.”

“Our Marines and our sailors are used to deploy[ing] overseas, whether it’s the Middle East or the Pacific,” she added. “So it really is an honor for us to be able to serve here at home, and especially to be able to protect the people, property and public lands of California.”

The battalion, part of 1st Marine Logistics Group based at Camp Pendleton, got tasked by I MEF for the mission and has Marines skilled in a variety of missions including road clearing, bridging, water production, explosive ordnance disposal and heavy equipment operations.

“The training is different, but it does have some similarities to what we do as Marines,” Mesta said. “It’s difficult. It’s challenging. But the (NIFC) cadre is here to make sure they are trained in all of the techniques that they need to be successful while they’re out there supporting this mission. So I’m confident that they’ll be able to do so.”

“They know this is going to be a lot of hard work in some very arduous conditions,” she said, noting “they are well suited for that. A lot of what they do as Marines, and not just as Marines but as engineers, is in similar conditions. So I think they are resilient and well prepared in that aspect.”

The battalion members, led by officer-in-charge Capt. Micah Tate, are assigned into 20-member strike teams. Each group has a senior leader – lieutenant, warrant officer or staff noncommissioned officer – and a corpsman and is paired with an experienced firefighter, said Gunnery Sgt. Warren Peace.

At Camp Pendleton on Friday, the Marines and sailors donned issued, fire-retardant uniforms – yellow shirts, green trousers and tan boots – along with red hardhats and blue backpacks stocked with personal safety gear and equipment. “They’ll have those with them at all times,” said Nicole Wieman, a U.S. Army North spokeswoman.

The familiarization training including the deployment of the fire shelter, which for the Marines and sailors was a green or orange practice shelter, about the size of a large sleeping bag. Additional gear, including actual fire shelters, is issued once they arrive at the fire base camps and get more on-the-job training, like how to swing a tool like a Pulaski, and how deep to dig, in areas already burned through, said Nate Budd, a Bureau of Land Management facilities maintenance supervisor at NIFC. They split up into smaller groups for a series of baseline knowledge on fuels and hazards and practical application lessons led by instructors from firefighting agencies.

One group of about 50 listened as Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service instructors guided them through the safety gear and shelter deployment. While many firefighters never deploy their fire shelter, the likelihood “is minuscule, but we have to train for just in case,” one instructor reassured them.

“If you’re going to be a shelter, you’re going to want to have your face really low to the ground,” he said. “Because what kills people in a burnover is rarely ever the heat on your skin. It’s that you get up and you breathe in super-heated air and it dries the tissues in your lungs. That’s what kills people, is actually asphyxiation.” So the best bet, the instructor offered, is to stay prone and low along the ground for the cleanest and cooler air. A face mask, such as ones they carry to protect against COVID-19 disease, can readily help keep them from breathing in dirt in such situations.

Budd told them about one firefighter who used a multi-tool he had on him to dig a hole to get more clean air. “He said the difference was night and day. … It was nice and cool and it was clear air, so carry some sort of tool with you,” he said.

Battalion members will be assigned as hand crews. “We don’t know what the assignment is yet,” said Budd, a trained firefighter and emergency medical technician and a strike team leader who will accompany the Marines and sailors. It will be his first time working with Marines and sailors.

“These guys already have it ingrained. They bring a level of just maturity already than what I’m used to seeing with rookies,” he said, “and they’re pretty well disciplined. Generally, in my world, that has to be taught… and they’re eager to learn and eager to work.”

The deployment marks the seventh deployment of active-duty Marines called upon to join firefighters in a ground attack on a wildland fire since two Marine infantry battalions from Camp Pendleton and six Army battalions were called to assist federal firefighters in the 1988 Yellowstone fires. The 7th ESB’s deployment is the 39th time since 1987 that the Defense Department has mobilized ground units to support wildland firefighting efforts, according to ARNORTH.

California National Guard Already Hard at Work

The California National Guard has already been supporting both state and federal firefighting efforts for weeks ahead of what is typically a late-September kickoff of fire season. Brig. Gen. Jeff Smiley, the director of joint staff for the California National Guard and the commander of Joint Task Force Domestic Support California, told USNI News on Sept. 17 that most of the 11 Western states were sending in aircraft and personnel to help, too, but that they were also dealing with their own wildfire outbreaks, straining the ability to respond.

“Our feelings on climate change here in California: California has been aggressively impacted by that; our fire season starts sooner and our fire seasons now go up until December, where they have not been that way over the last I would say maybe six years ago. So every year our fire season is growing in length, and so I can’t tell you when” the season will end this year. A typical fire season years ago might start in late September or early October and rage until early November, when the winds change.

“I don’t see really an end until we get some rain and that puts all these fires out.”

The California National Guard made perhaps the most dramatic rescue in the Creek Fire, where the Marines and sailors are headed, with an Army CH-47 Chinook and UH-60 Blackhawk doubling and at times tripling the number of passengers they’re allowed to carry in order to save as many vacationers as possible at a lake that was overcome by the fire.

Sgt. George Esquivel and Sgt. Cameron Powell were the two flight engineers on the Chinook, and they said their fire training helped them understand how their aircraft would perform in the smokey and windy conditions, how their downwash might affect the embers and flames they were flying over, and how many passengers they could cram onto their helicopter without overstraining the aircraft.

At each turn, they said, they were maxing out the limits of their helicopter to save as many people as possible. They landed on a concrete boat launching pad on the lake that had a 13-degree incline, right at the limits of where they could land in windy conditions.

And whereas they are supposed to be limited to 33 passengers at a time, they took on 67 on the first lift, 102 on the second lift and 37 on the third and final lift.

“We were pretty heavy on that second lift, but we just didn’t know if we were going to be able to make it back a third time. The smoke and everything was starting to come in, so we needed to pile as many people in as we could to maximize our rescue mission,” Powell said.

“We gotta do what we gotta do in that situation.”

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Kipp Goding was flying the Blackhawk in the same rescue mission and is supposed to carry 11 passengers; he picked up 15, 22 and 21 passengers on his three flights into the fire.

“Each individual crew is monitoring each other: how do you feel, how well can you see, do you feel comfortable, is it safe for us to continue. And then we also communicate between the two aircraft to say, hey, this is what I’m seeing, this is what I’m feeling, and make sure that we’re challenging each other so we don’t get too far into an area that we can’t recover the aircraft safety back,” he said during the interview.

“We took out every person that wanted to come out. Each time we went there were more and more people assembled next to the aircraft, and we took more in later turns that, when we first went there the first time it didn’t seem like there were that many people, but more just kept coming and coming and coming,” Goding said.

“When we told them this was our last turn, there were only two people that left that stayed there; they both voluntarily stayed there, they said they were going to spend the night.”

Esquivel, who was the first one to leave the aircraft upon finding the boat launch landing zone and went to gather people awaiting rescue, said “it was, the best I can describe it is just absolute chaos. Nobody knew where to go, nobody knew who to talk to or how to get help. And it was kind of just … apocalyptic in there. We’re all human, we’re scared, we don’t know what to do, but all our training kicks in.”