Several Navy program officials and resource sponsors today outlined how they’ll spend the next couple years giving Congress enough confidence in unmanned surface and underwater vehicles to allow the service to move from prototyping into programs of record.

Across the entire family of USVs and UUVs, the Navy has prototypes in the water today for experimentation and in tandem is making plans to design and buy the next better vehicle or more advanced payloads, with the idea that the service will iterate its way to achieve congressional confidence and authorization to move forward on buying these unmanned systems in bulk.

Rear Adm. Casey Moton, the program executive officer for unmanned and small combatants, spoke today at the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) annual defense conference and provided an update on the status of his portfolio of UUVs and USVs, some of which have run into trouble with lawmakers not convinced of their technical maturity and their tactical utility.

Anticipating audience questions, he said in his speech, “what about Congress? What about the marks and the report language and the questions? So I’m going to put some of that into context from my perspective. I believe the discussion with Congress has not been about if unmanned vessels will be part of the Navy. ‘If’ has not been the focus. I don’t even believe right now that ‘if’ is a major question. The focus has been on ‘how,’ with a healthy dose of ‘what,’ in terms of requirements and mission type. And of course, ‘how many’ is a question. How many, I will not focus on today. How many is dependent on Navy and [Office of the Secretary of Defense] force structure work. But for PEO USC, how many is ultimately important, but our focus now in this prototyping and experimentation and development phase is on the how, and working with our requirements sponsors and the fleet on the what.”

The most ambitious part of the Navy’s current plan calls for the start of a Large USV program of record in Fiscal Year 2023, despite the LUSV being the piece of the family of USVs that Congress takes issue with the most. The Navy intends for these ships to be armed with vertical launch system cells to fire off defensive and offensive missiles – with sailors onboard manned ships overseeing targeting and firing decisions, since there would be no personnel on the LUSV. The House and Senate armed services committees have said they’re a long way from feeling comfortable with the concept of operations and the technological maturity and reliability.

How the Navy Will Advance Unmanned Systems

Moton said the “how” piece is clear: putting unmanned prototypes in the water, learning from them, wrapping lessons learned into acquisition plans for the next round of prototypes, and then eventually moving into acquisition of program of record UUVs and USVs.

He and Capt. Pete Small, the unmanned maritime systems program manager at PEO USC, ran through the status of all the components of the USV and UUV families of systems and explained how the iterative process was playing out for each piece.

On the Large USV, Moton and Small outlined a transition from the Pentagon-purchased Overlord USVs (OUSVs) in the water today, to two Navy-bought OUSVs that just started fabrication and will supplement in-water experimentation and tactics development, to the ultimate LUSV program of record.

Moton said the two OUSVs in the water today had done a range of transits and operational vignettes in increasing complexity since 2018. They have proven they can safely encounter fishing, merchant and recreational boats and follow the maritime rules of the road to navigate around them. The OUSV’s longest transit so far was about 3,200 nautical miles over 181 hours from the Gulf Coast to the East Coast, and the service is working its way up to a 30-day transit event. In FY 2021, testing with these first two vessels will include using government-furnished payloads and command, control, communications, computers and intelligence (C4I) systems, as well as hull, mechanical and electrical (HM&E) upgrades, to conduct longer-range and more tactically complex autonomous activities.

Small said he was confident all these C4I and payload tests would be done and would prove the technologies’ readiness “all prior to initiating LUSV procurement” in FY 2023.

Even as this confidence-building work is taking place, Small noted that on Friday his office awarded six industry study contracts to begin to inform LUSV requirements “for an affordable, a capable and a reliable platform.”

On the Medium USV, the story is the same: a prototype in the water, another on the way, with an eye towards moving from prototyping into a program of record.

Small said the second Sea Hunter medium USV launched in August successfully and on time and will go into fit-out and testing before delivering to the Navy’s Surface Development Squadron One (SURFDEVRON), where the first Pentagon-bought Sea Hunter is already contributing to concept of operations (CONOPS) development, fleet training and familiarization and other efforts. Moton said the first Sea Hunter craft had already participated in two Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training (SWATT) events this past year and in FY 2021 would participate in multiple fleet exercises and training events. Upcoming work will focus on manned warship control of multiple USVs, testing command and control of the USVs, operating the USV as part of a surface action group, and training sailors to use them, as well as further developing and refining CONOPS.

Looking towards the program of record, in July the Navy awarded a contract to L3Harris for an MUSV prototype that will help bridge the Sea Hunter prototyping work with the ultimate program of record.

By the 2023 planned start of the LUSV acquisition, Small said, the Navy would have the two Pentagon-bought Overlord USVs, the two Navy-bought OUSVs, the two Pentagon-bought Sea Hunters and this latest Navy-bought MUSV prototype in the water, all proving that the service is on the right path and should be allowed to start buying in numbers.

Rounding out the Navy’s USV family of systems is a small USV that Small said also shows the Navy’s desire to keep iterating and adding more capability. The Textron-made Common USV, now called the Mine Countermeasures (MCM) USV, is in production for its original minesweeping mission. Textron had already delivered three for testing and is building three more now under a low-rate initial production contract, Small said, and the Navy is conducting Littoral Combat Ship integration testing with the USV in sweep mode. Next in line is the mine hunting package, where the USV would tow sonars. That configuration is in craft-level testing now and will begin LCS integrating testing in FY 2021. Next in the pipeline is mine neutralization, which will start development in the next year, Small added.

On the unmanned underwater vehicle side, the iterative development continues.

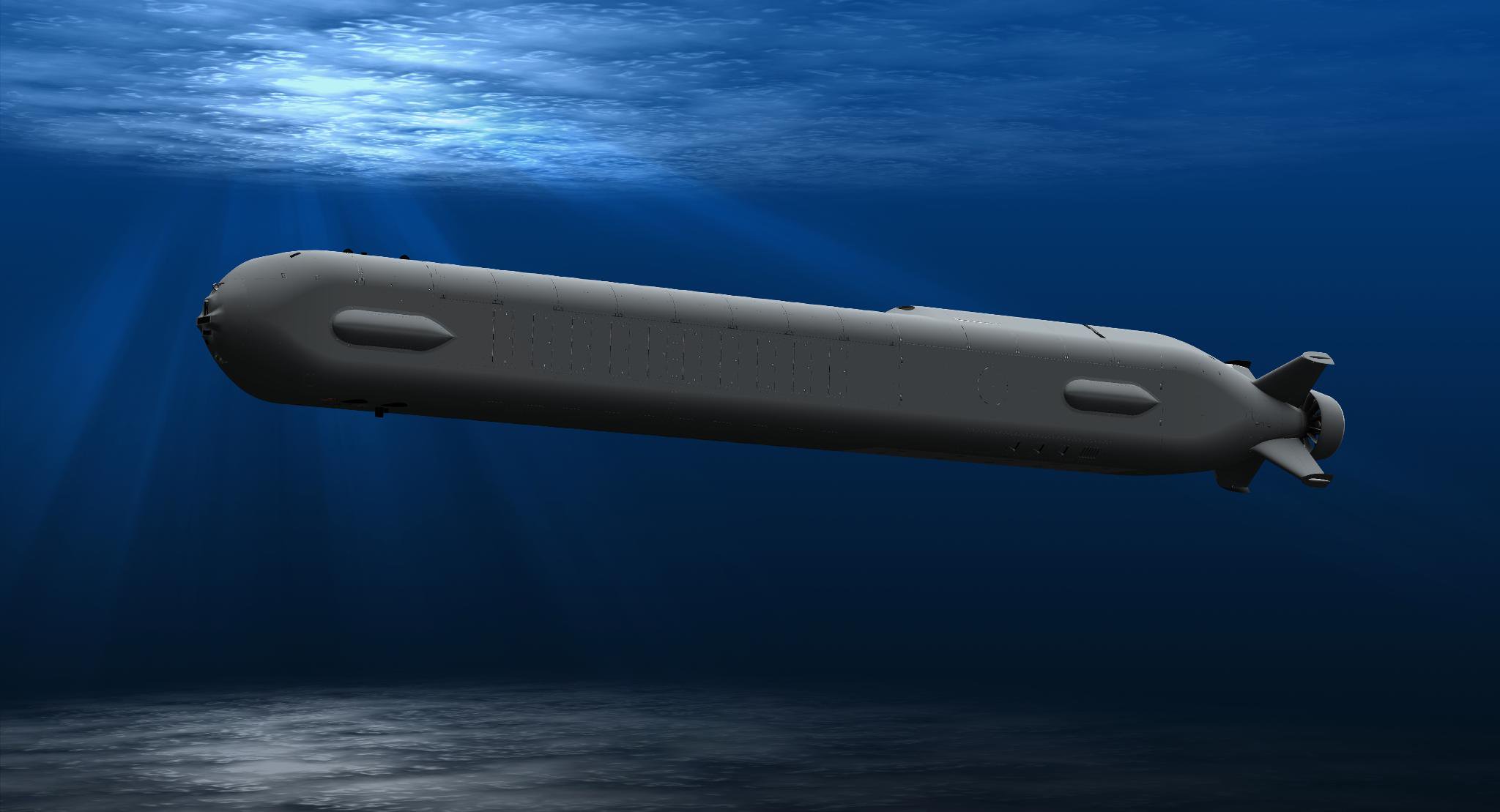

Small said on the Extra Large UUV, Boeing’s Echo Voyager is in the water now as a prototype that’s representative of the size and architecture of the Navy’s program of record Orca XLUUV. Boeing is building the first five Orca prototypes now, and the Navy is preparing to receive those vehicles and conduct testing on the pier-launched UUVs before moving into a full-rate acquisition program.

On large UUVs, UUV Squadron One (UUVRON-1) has been working with two prototypes from the Penn State Applied Research Lab – named LTV-38 and LTV-48 – that are a representative size of the sub-launched large displacement UUVs the Navy wants to buy. The UUVRON has been working out the launch and recovery procedures, even as the first Snakehead LDUUV Phase 1 vehicle is well into fabrication, Small said. That first Snakehead will deliver next year and begin test and evaluation activities, even as the Navy finalizes its request for proposals for the Phase 2 Snakehead LDUUV design that will be the capability the fleet fields.

On medium UUVs, the Navy purchased five Knifefish UUVs for hunting bottom and buried mines. General Dynamics is building those Block 0 UUVs now, even as the Navy is developing a more capable Block 1 configuration for the next UUV order. Small said the first five systems being built now will later be upgraded to the Block 1 configuration.

The Razorback medium UUV is used by the submarine community for preparation of the battlespace missions, and the service is taking delivery of nine vehicles that are launched and recovered from a submarine’s dry deck shelter that divers use to come and go from submarines. Two of the nine have already delivered and are being used in experimentation.

However, Small said that torpedo-tube launch and recovery is “the gold standard we’re working towards” so that divers aren’t needed to help with the UUVs, so even as the first vehicles continue to deliver, the Navy is already in source selection for a follow-on Medium UUV that will be torpedo-tube launched and will replace both the original Razorback and the Mk 18 Mod 2 mine countermeasures UUV used by expeditionary MCM companies.

Moton said during his keynote speech that this work on the UUV and USV vehicles is being supplemented by work at the Program Executive Office for Integrated Warfare Systems to adapt Aegis Combat System common source library code and virtualized hardware for the USVs, and work at PEO C4I to help bring unmanned systems into the netted naval force. He also credited industry for rising to the challenge, with 40 companies of all kinds and sizes under contract with the Navy under an indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contract for USV family of systems related work, and the six LUSV study contract winners – of eight bidders total – representing a range of expertise.

“All of these efforts – the acquisition work with the Navy and industry, the fleet work, the CNO-directed and integrated Navy work – will together over the next two to three years have us positioned to answer the ‘how’ questions and the ‘what’ questions before we buy program-of-record vessels,” Moton said.

“We will continue working closely with Congress and doing what is right and appropriate for this stage of fielding these revolutionary new systems” and addressing their concerns and recommendations along the way.

Resource Sponsors Are All In

Moton also led a panel of Navy and Marine Corps resource sponsors who are determining how unmanned systems will fit into the surface warfare, undersea warfare, expeditionary warfare and Marine Corps acquisition budgets despite expected flat or declining toplines. Each was confident they wanted unmanned systems in their portfolios but had slightly different reasons for wanting to include unmanned.

Maj. Gen. Tracy King, the director of expeditionary warfare on the chief of naval operations’ staff (OPNAV N95), said he wants to put a robot in a potential minefield during mine countermeasures operations instead of putting a manned ship at risk. The fact that the unmanned craft won’t need to be survivable will inherently make them cheaper, making it easier to budget for them in numbers.

Rear Adm. William Houston, the director of undersea warfare (OPNAV N97), said unmanned will allow the Navy to get into places that manned submarines can’t go, either because the UUVs can be designed to be less detectable or because the consequences are lesser if a UUV is discovered.

Rear Adm. Paul Schlise said the USVs in his surface warfare directorate (OPNAV N96) portfolio would provide more persistent sensors and supplemental fire support than the Navy could afford to buy with manned ships and aircraft alone.

All agreed that USVs and UUVs would find room in the budget, since ongoing future force planning efforts have reaffirmed that manned/unmanned teaming will be critical in a future fight.

But Houston said “how fast technology matures, how well we’re able to prototype it, and how well we’re able to get the certainty as we’re shifting from a balance of completely manned systems to a more hybrid approach” will determine how fast the unmanned systems will be incorporated into future undersea warfare budget requests. He called for a measured approach as the iterative prototyping process plays out because, while it would be an advantage to move to unmanned systems because they’re cheaper and therefore he could afford to put more assets in the water, he doesn’t have the money in his budget to go all-in on something that ultimately won’t meet the fleet’s needs.

Manned/unmanned teaming will happen under the water, he said, it’s “just a question of how fast and how much we do that” based on Moton’s ongoing prototyping work.

Schlise praised the process too, as well as the contributions that Congress has made – particularly the Senate Armed Services Committee’s insistence that the Navy use land-based testing to prove the reliability of mechanical and electrical systems, which will have to run for weeks or months at a time without a crew onboard to conduct daily maintenance activities.

“That’s something that’s new. Obviously the engineering plants of today on surface ships, on a manned ship, there’s a good amount of sailor interaction to keep those systems running, that’s how they were designed,” Schlise said.

“So I actually think this is a good ask Congress has asked of us, to prove out some of these systems. And our plan is to do some of that with industry, to have them bring best-of-breed options to the table to test out and see if they’ll meet our endurance and reliability requirements. So that’s another piece of this requirements process that we’re continuing to hammer out here as we go forward with Congress as a key stakeholder in this.”