National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Navy are formalizing a partnership on unmanned maritime systems and the policies that will govern their operations, as each organization stakes out their own unmanned futures.

The agreement is the result of the Commercial Engagement Through Ocean Technology Act of 2018, which called for greater collaboration between NOAA and the Navy and was sponsored by Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.).

The law “requires NOAA to coordinate research, assess, and acquire unmanned maritime systems with the U.S. Navy, other federal agencies, industry, and academia,” reads the act.

The memorandum of understanding, announced this week, between the Navy and NOAA sets a framework to develop policies and procedures to make it easier to share information as the agency and the service develop unmanned systems. NOAA recently established its own unmanned systems road map it will develop with other federal agencies.

For example, “the Navy has significant capacity for testing and evaluating marine unmanned systems,” Charles Alexander, chief of the planning and performance management division at the NOAA Office of Marine and Aviation Operations, told USNI News in a Wednesday interview.

“We intend to collaborate with the Navy on doing that on their test ranges and their facilities. The Gulf of Mexico is a good example.”

Other areas of collaboration are developing the autonomy technology to allow unmanned maritime vehicles to avoid other craft and follow the international maritime rules of the road.

For both the Navy and NOAA, a major appeal of unmanned is to provide a persistent sensor picture for a specific area. The Navy’s MQ-4 Triton unmanned aerial vehicle is now deployed to monitor the open ocean for up to a day at a time, and future unmanned systems could field a variety of sensors to detect adversaries. For NOAA, the persistent sensors could provide better understanding of hard-to-study species, like whales, or ocean salinity over time.

The Navy and NOAA have had past collaborations in unmanned systems.

At the start of this year’s hurricane season, the agency, the service, the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System and a collection of academics released 30 ocean gliders to monitor a variety of conditions at sea to help better predict the behavior of hurricanes.

“The hurricane gliders will collect data in the upper ocean where the Gulf Stream, Loop Current, inflowing fresh water from rivers, and other features can play a role in the strengthening or weakening of hurricanes,” reads a statement from NOAA.

Sharing oceanographic data between the Navy and NOAA is also a high priority for the partnership.

“How do we make the data more interoperable with the Navy? And I have a lot of oceanographic data, but it’s hard to share it when it’s not interoperable,” Alexander said. “We’re not using the same protocols. That’s something that we think we can advance quickly with some of the progress we’ve made at NOAA.”

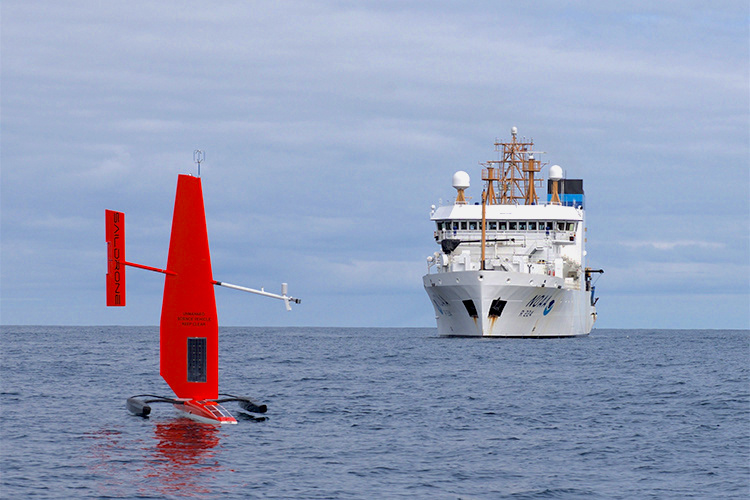

The Navy is also interested in how NOAA is contracting out how they gather some of their data. For the last several year, the agency has used sail drones as part its research.

“We don’t own the platforms, but we’ve significantly contributed to the modification of them for our uses in doing climate oceanography, fishery science, and ocean mapping,” Alexander said.

“There’s some unique lessons learned there that the Navy is very interested in and how we use data as a service from a company, like with the sail drones, where we’re not buying the platforms we’re buying the data.”