The guided-missile destroyer USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) is resuming operations in 7th Fleet three years after a devastating collision killed 10 sailors.

Last week, the ship and the crew completed the six-month basic phase training, a key milestone before returning to the fleet.

“We’re back, and we’re more ready and we’re more lethal than ever before,” Cmdr. Ryan Easterday, McCain’s commander, said during a conference call with journalists on Tuesday morning, Japan time.

The crew aboard the Yokosuka, Japan-based McCain started the basic phase in November following a two-year maintenance period that included upgrades to some warfighting systems. This spring, the ship got underway for certifications and a final battle problem.

“They have proven that ‘Big, Bad John’ is absolutely ready to rejoin the fleet,” Easterday said, crediting the crew’s hard work and enthusiasm for the successful certification in 23 separate skill and warfare areas. “We’ll continue to build on our training successes.”

Easterday served 18 months as the ship’s executive officer before taking command of the ship in July 2019. He began that XO tour just four months after the fatal Aug. 21, 2017 collision between the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer and the chemical tanker Alnic MC killed 10 enlisted sailors.

The National Transportation Safety Board found “a lack of effective operational oversight of the destroyer by the U.S. Navy, which resulted in insufficient training and inadequate bridge operating procedures,” according to the investigation. The NTSB investigation released last year put blame more widely on the service than the Navy’s own assessment pointing blame largely at McCain’s then-commander. The collision came just two months after the guided-missile destroyer USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) collided with the container ship ACX Crystal off Japan on June 17, 2017, killing seven enlisted sailors.

Both fatal collisions, along with a minor collision with a fishing boat and a ship’s grounding, prompted the Navy to order a comprehensive review of the surface fleet led by Adm. Phil Davidson, then-head of U.S. Fleet Forces Command. Since then, the Navy has implemented a series of changes to surface fleet training – and not just focusing on ship-handling and navigation but also addressing issues such as the manning and assignments of ships’ crews and even policies and practices tackling issues such as crew rest and fatigue.

McCain “is one of the first ships to benefit from these changes,” Easterday noted, “including revised individual and unit training, updated career paths and practices, and a renewed focus on professional seamanship and navigation.”

Recent years’ changes to the surface force training cycle also has given ship commanders more flexibility to train their crews, aside from what typically had been rigid training and maintenance schedules. “I worked really hard – and the crew worked really hard – to find opportunities,” Easterday said. “In places where we were able to meet certain certifications criteria early, we were able to buy that time back, and then I was able to use it to raise our training to the next level and do extra stuff.”

“We worked the schedule to allow extended underway periods,” he said. “Frequently, during the basic phase, you kind of go out for two or three or four or five days at a time to knock out the things that you’ve got to do during the events you are doing and then you come back to port. We tried to schedule underways that were 10 days or longer, to enable the crew to really get into the underway rhythm of the condition three watch bill, allowed us to practice more additional events, (like) underway replenishment, fit in more live-fire exercises. We really just looked at every opportunity where we could squeeze out even just a few hours to do more stuff. I think that has really paid dividends for us over the last few months.”

COVID-19 impacts

McCain was at sea for a 10-day underway for training in early March when the COVID-19 pandemic became more widespread and the Navy began to lock down ships and bases in attempts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus. The ship entered a “bubble” after extending that underway and returning to Yokosuka in early April for some required in-port training and maintenance. That work, though, required 70 to 80 people to visit the ship daily, making it hard to maintain that COVID-free bubble.

“We put a lot of controls in place to make sure the people we brought on the ship were bringing the virus with them,” Easterday said.

It was also hard to cut the workforce in half “and still do the things that we needed to do,” he said. “We are still kind of grappling how to do that going forward, as we continue with the work that we have. We’re not able to just send most of the crew home most of the time… We’ve still got missions to do and we’ve still got work to do, but we’ve tried to comply with that workplace reduction as much as we can, consistent with our mission objectives.”

The ship has taken measures to ensure the virus doesn’t affect the crew and ship operations in line with fleet and federal guidelines, and there’s extra cleaning to thwart any spread. “So far, we’ve been successful. But we’re guarding against complacency and not letting up on our efforts,” he said.

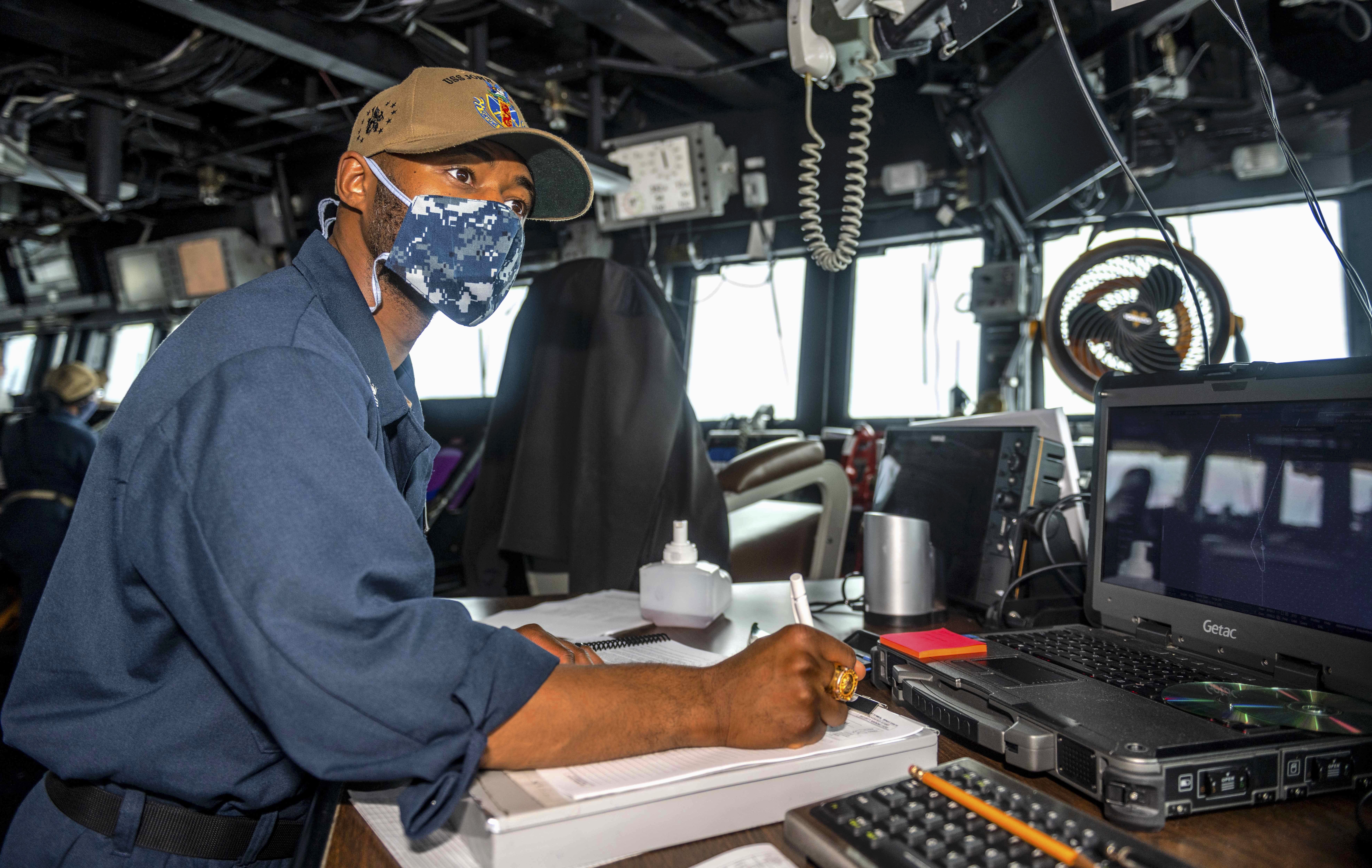

Social distancing “is pretty difficult in the close confines of the ship, but we’ve really made an effort” and taken steps “as much as we can,” such as avoiding large meetings and briefings or holding them topside, Easterday said. The ship screens everyone who comes aboard with questionnaires and temperature checks. Hand-washing stations are set up on the pier when in port. Masks or face coverings are required at all times. Each crew member received a notebook and must keep a log of all their close contacts. Easterday acknowledged that’s complicated since training and operations on ship involve lots of close interactions but necessary “to help manage an outbreak, should it occur.”

Simulator training

During basic phase, McCain’s crew got more than 200 hours of simulator training, much spent on practicing ship-handling at a navigation, seamanship and shiphandling trainer operated by Afloat Training Group Western Pacific.

“We can integrate a full navigation and ship-handling team in the simulator,” Easterday said.

“We were lucky enough to take advantage of opportunities when other ships were out operating and use a lot of extra time in that simulator.”

The simulators provide good training for junior officers “who are learning to be officers-of-the-deck or trying to maintain proficiency to practice special evolutions that we don’t do very often,” he said. “We do high-density traffic scenarios, underway replenishments, some of those kinds of things that you don’t necessarily get to practice very often especially when you’re in the yards or in the basic phase. That helped build those individual skills. The upgrades to the simulator also allowed us to practice that team cohesion.”

Easterday said the integrated bridge-and-navigation system has its own simulator capability, “so we used that several times pretty consistently as well. During fast cruises, we set it up and ran it in real time and allowed watch teams to essentially drive the ship in the simulator while we’re executing the scheduled events for the fast cruise.” Weekly training led by the ship’s navigator, he said, gives junior officers “practice on standard commands and basic ship-handling and then familiarity with the user interfaces on the equipment as well, so it’s been really fantastic.”

A major portion of McCain’s crew has turned over since the 2017 collision, and the crew includes many junior sailors and officers fresh from basic or “A” or “C” schools who haven’t deployed yet aboard a ship. “That’s what the basic phase is for, to take all those sailors and then set them through the paces and start them out by individual training so they can learn their job and their watch station and their role,” Easterday said. “And then team training to help them function within the context of a team., and then in the final battle problem really putting that all together and having the whole ship operating and fighting together as a single unit.”

With basic phase completed, “we’re going to go out and we’ll continue to train and we’ll continue to learn,” he said. “I’m absolutely confident in the crew’s ability to safely and effectively complete any mission that we’re tasked with.”

After starting with classroom training, “as we developed and moved onto the warfighting training, a lot of that is done in port, which allows us to use the ship’s combat systems in a training mode as a kind of simulator,” Easterly said. “We can actually plug into networks that allow external organizations to inject and stimulate the systems for more intense and more realistic combat training than we can do at sea by ourselves. We can get on the conns and talk to real people on the radio.”

Building bonds

The culminating, final battle problem is designed to stress the crew through complex warfighting and damage control scenarios. During McCain’s final battle, “we actually destroyed the bridge,” he said. “We put a smoke machine in there and posed a bunch of personnel casualties, which forced the damage control organization to figure out how to fight the fire up there, which is a place that you don’t normally find a fire.

“That forced the first-aid organization to figure out how to deal with all of the personnel casualties up there, and it really forced the watch teams to figure out how to regain control of the ship from alternate controlling stations, shifting thrust and steering controls to alternate stations. The CIC watch team then basically having to take over the navigation and driving of the ship while still fighting a warfighting scenario in combat.”

Such stress in training, Easterday said, is important to “make them think through and prioritize what they’ve got to do next and solve these problems in real time, and then frankly how to fight through the fatigue. We started some of these scenarios very early in the morning and ran them all day. It was pretty intense, and a great capstone event to demonstrate the proficiency that we developed over the last few months.”

The crew, he said, “bonded together through the repair period, and even more so through the last six months of basic Phase. They’re hungry, they’re eager to learn and they’re getting really, really good at it.”

Easterday wasn’t aboard McCain when the collision happened, but when he became the XO he jumped into leading what he described as “a massive rebuilding and restoration project… It’s been absolutely incredible watching what the crew has done over the last two-and-a-half years putting the ship back together, putting the crew back together, and bringing the ship back into the fight.”

Every day when he enters the ship, Easterday passes a memorial plaque engraved with the names of the 10 sailors lost in the collision. “Everything we’ve done since then honors their memories and, more importantly, carries on their work. Our successes are their legacy, and I’m absolutely confident to say that ‘Big Bad John’ is back.”