This post is the first in a two-part series on the naval aviation community’s effort to build better readiness and how that is changing the future of naval aviation.

This post has been updated to note that the readiness push resulted in 90 more mission capable Super Hornets in March and 340 more aircraft overall compared to the same time last year.

SAN DIEGO, Calif. – “I love data, it’s just awesome.”

When Commander of Naval Air Forces (CNAF) Vice Adm. DeWolfe Miller took command in January 2018, years of tight budgets had robbed the naval aviation community of maintenance and spare parts funds, leaving some squadrons with just enough flyable aircraft to keep their pilots qualified but not enough to do any kind of sophisticated training.

Though money was starting to flow back to readiness accounts, only about half the F/A-18E/F Super Hornets were mission capable and could be used for training and operations. That fall, then-Defense Secretary James Mattis ordered the services to increase to an 80-percent mission capable rate for their fighter fleets in just one year.

Miller’s love of data helped solve a problem that couldn’t be fixed through more money alone.

Speaking last month during the WEST 2020 conference, Miller said the difficulty and urgency of Mattis’ challenge meant naval aviation had to rely on data-driven decisions.

“It takes away ‘I think this,’ ‘I think that,’ the person with the most stars wins,” he said during a panel on readiness.

“Data don’t lie.”

By embracing data and developing the Naval Sustainment System and Performance to Plan frameworks for aviation readiness, Miller said, the Navy had 340 more aircraft flying in March 2020 compared to March 2019, including 90 more Super Hornets.

“That’s the power of data and data-driven decision-making, and it’s making results,” he said.

Asked by USNI News for an example of how data changed his approach to boosting aviation readiness, Miller said an initial dataset in 2018 showed the two quickest ways to improve readiness were to tackle intermediate-level maintenance and manning at the squadrons. Miller ordered improvements in both areas, but continued data analysis showed that, “even if you do that –this was specifically for strike fighters – it said you are not going to get the 80-percent mission capable rate in your strike fighters. And that’s when we, all the sudden, because of that, made the decision to go ahead and do reform basically across all the tenets of naval aviation: at our squadron level, our intermediate level, our depot level, the way we do engineering, the way we run the operations center now and make decisions – all of that was because of the insights provided to us through data. And the results are, we’re at 341 Super Hornets (mission capable). We’re at 340 more airplanes (of all types) flying today than last year. So it really is a, if you will, a testament to the power of data-driven decisions.”

Miller said he’s made sure that everyone – from the squadrons up to the chief of naval operations – has access to the same data on unit readiness and manning through his weekly Air Boss Report Card, to ensure the proper alignment and prioritization of money, manpower, parts and leadership attention.

Dedicated Data Analytics Team

The CNAF’s Force Readiness Analytics Group (FRAG) informally started working in the spring of 2018 and formally stood up that September to take existing data in the aviation realm and apply machine learning and data analytics models to turn routinely collected information into something more actionable and predictive.

Cmdr. Jarrod Groves, the FRAG director, told USNI News in an interview last year that the FRAG had full support from Miller, in part because big results were expected from only modest increases in budget lines.

“We have to be able to man, train and equip better, more granular, more with outcomes in mind: mission capability rates, fire execution. How do we be very precise with our resourcing of that to enable those outcomes?” Groves said in the interview at the FRAG office at Naval Air Station North Island.

Though the military sometimes wants to wait until a system is perfected to begin using it, Groves that that wasn’t an option because “we need answers today. Leadership can’t wait a month to go gather the data, figure out what your null sets are. I phrase it as, we learn by do. We know what data we have, and working with the experts we know what the data means. And by doing that, by bringing it together in one place, we understand where our gaps are at. And the question is, how do we close those gaps: is it other data sets, do we need another software tool or something?”

The early days of the FRAG’s work weren’t easy, with data being siloed and not always kept in compatible formats. Groves said the Navy has 20-plus years of data on every maintenance action that has taken place on every airframe, as well as every time a pilot flies, every training event associated with each sortie, the financials for every flight hour flown or maintenance action taken, and so forth – but some of the data is recorded daily versus monthly, and other variables that didn’t make them all easy to mesh together into a single database.

“Over the years we’ve had different organizations stand up different software and different databases to collect information to answer their questions or to answer their interests. And it wasn’t really in the scope of the technology to say, how do we do this in one big cloud,” he said.

An early win for the FRAG was looking at 84-day aircraft inspections. Under the Naval Sustainment System, a squadron-level initiative was to improve scheduled maintenance, including inspections on each airframe that take place about every 84 days. There was no real standard for how long those inspections should take, and completion times ranged from two days to 12 days based on how each squadron prioritized that routine scheduled maintenance. Groves said the FRAG and CNAF wanted to better measure those maintenance evolutions – for most squadrons, at least one aircraft is undergoing an 84-day inspection during any given week, meaning slow completion times can have real consequences on the number of up aircraft and therefore the number of flight hours the pilots can achieve that week.

After some work diving into the maintenance action forms and other available data, Groves said, CNAF determined that the goal should be three days for the inspection and that the bulk of inspections were actually taking about five days. Armed with that knowledge, the air wings on the East Coast and West Coast have both been able to bring the inspection durations down by transparently sharing these numbers weekly and looking at what resources are needed to help squadrons that aren’t meeting the three-day goal.

In a more complex initiative, the FRAG looked at how safety affects readiness – specifically, how towing mishaps that cause Class C and Class D damage affect readiness rates in squadrons.

“For the longest time we’ve been reporting mishaps A through D and the day and the community, but we were never able to really understand the impact to the jets’ mission capability. So Air Boss asked the question, what’s the average time, due to a mishap, how long does it take to get back to mission capable? So we realized, well heck, in our safety database we have an aircraft number, and in our maintenance reporting system we have, by every day, we have the status of that jet. So we could actually tie when the mishap happened to the status of that jet, and then how long it took to get back to MC,” Groves explained.

“And that was just one of the questions he’s had. So now we can actually measure for [Fiscal Year 2019], due to ground mishaps, a jet takes this long to get back to MC, and then track the status of that jet. And then the next question is, how many maintenance man hours went into building that jet back up? So we can go into another data set, same thing, tie the [maintenance action form] to the date-time period and aggregate all those maintenance man hours.”

Once the knowledge exists on how a Class C mishap affects the entire squadron’s readiness, smart decisions can be made specific to an individual squadron and where it is in its deployment cycle.

“Hey, we just had another mishap, the aircraft is fine, pilot is fine, but there’s going to be an impact to this squadron: it’s going to take them probably 40 days and 1,000 maintenance man hours to rebuild this jet, and they don’t really have, if they’re in this phase of the [deployment] cycle when they’re trying to execute their flight schedule, there’s going to be this much more drain on resources to this jet. So maybe we move that jet to another squadron, or maybe we move that to another location so they’re not having to rebuild it, or bring in contractors to do that. So understanding the result not only on the jet but the squadron and where they’re at,” Groves explained.

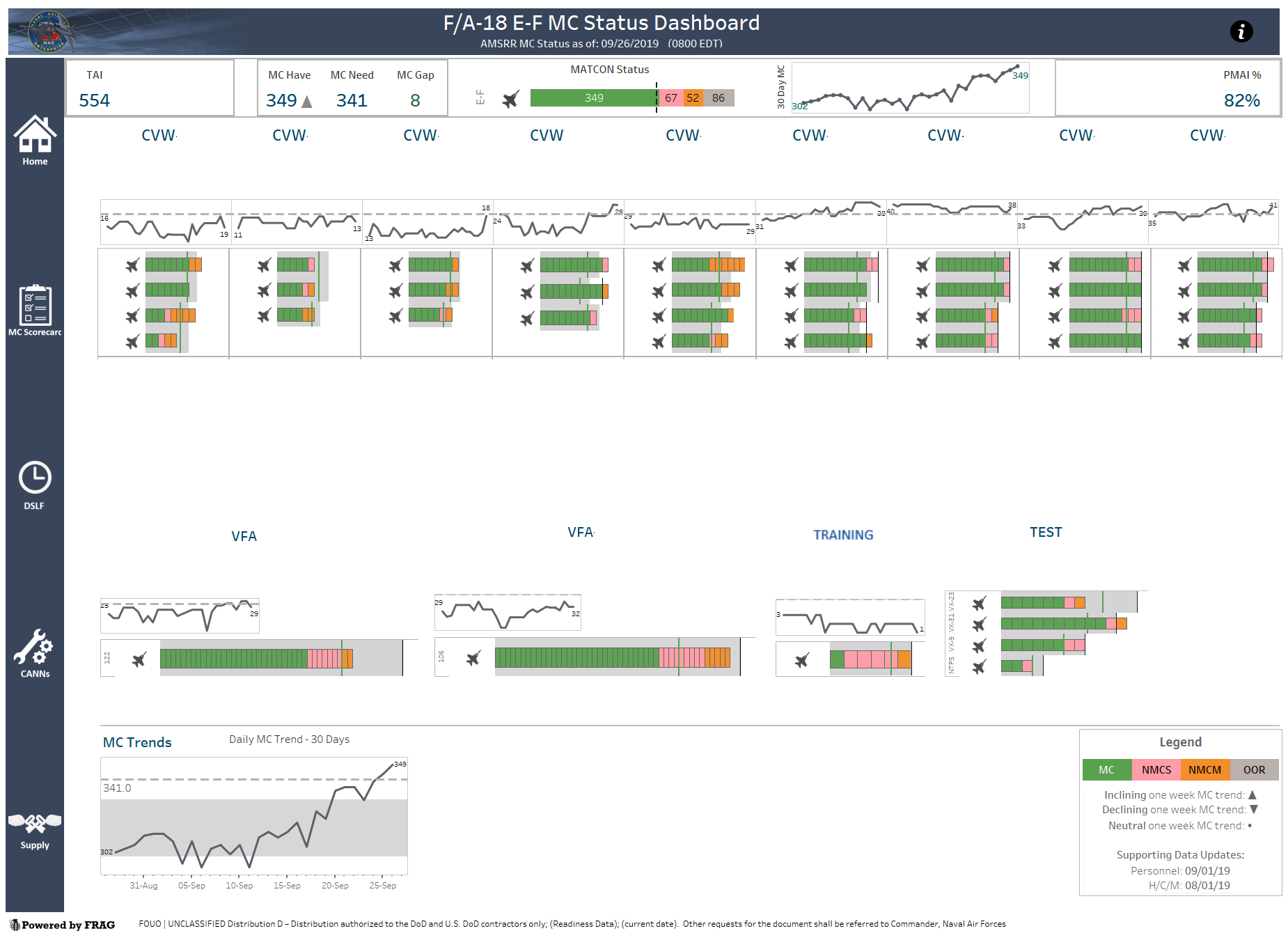

And then there’s the dashboard, used to generate the Air Boss Report Card, that’s the culmination of culling data from different sources, generating a user-friendly interface and applying machine learning tools to auto-update the dashboard every morning.

Through the dashboard, a viewer could look at the entire Super Hornet inventory, for example, and see all relevant information: total inventory, required versus actual number of mission capable aircraft, 30-day mission capable trends and more across top; a look at each squadron, organized by carrier air wing, and a color-coding of each jet’s status of mission capable, down for maintenance or down for supply; a look at other Super Hornets outside of carrier air wings, such as training and testing units; and more.

Clicking on an individual squadron shows more information: flight hours; the fit, fill and experience level of the maintainers; and additional notes for the air wing about the squadron’s performance or needs.

The key is the data being automatically pulled and updated daily. Groves said that, to generate the dashboard’s information by hand for any given day would take several weeks, since the data comes from CNAF, from Naval Air Systems Command, from Naval Supply Systems Command and more.

The Department of the Navy (DoN) earlier this year awarded a DoN A+ Award to the FRAG for their efforts. The award citation notes the “team implemented the Performance to Plan (P2P) mandate to increase fleet readiness and a rapid data-driven decision making process for senior leadership. The team created machine-learning models for determining the monthly number of mission capable jets per squadron by incorporating manning-training-equipment datasets from Naval FA-18 squadrons.”

Another award description adds that they “developed machine-learning models to track and predict aviation fleet readiness. Their work analyzes historical information to seamlessly view data and predict future performance, improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and readiness of the Naval Aviation Enterprise.”

Groves told USNI News that the next step is using the data to become even more predictive, to not just reveal hidden readiness deficiencies but to actually avoid them in the first place.

“We’re just tackling the easy stuff. Now it’s, how do we do more, how do we start to get predictive with certain things, and tackling some of the gaps in the data and how do we augment that? There’s a lot of work, there’s a lot of people trying to do stuff in this realm. We were told to run with scissors and be first to the whiteboard; people are now starting to come online, and how do we do what you guys are doing?” Groves said.

“The whole goal is to help others join the practice so they can use their data in the same way.”

Miller, during his WEST panel discussion, said he too believes not just CNAF but all the type commands would rely more and more on predictive data analytics.

“That’s where we’re really finding, at least through that leadership, that alignment of that data, we can get in front of a lot of the issues we’re facing,” Miller said.

“That is a big piece of our business at the TYCOMS now, and I don’t see that going away any time soon, I see it just continuing to evolve.”