An aging and inactive government fleet dependent on a shrinking pool of merchant mariners to get underway is how a new report describes the U.S. military’s strategic sealift capability.

The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments took an in-depth look at the health of the nation’s maritime industry – including the fleet of U.S.-flagged ships in the sealift fleet, the public and private shipyards asked to build and maintain the vessels and the workforce expected to serve aboard the fleet.

If a large-scale troop build-up were needed to occur quickly overseas, the U.S. strategic sealift capability would be unlikely to meet the Pentagon’s dry cargo, munitions or tanking needs, according to the report’s authors, Bryan Clark, a senior fellow at CSBA; Timothy Watson, a research fellow at CSBA; and Adam Lemon a former research assistant at CSBA and currently a staffer for Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.).

“To effectively compete, the U.S. government should stop considering the commercial and national security contributions of the maritime industry as largely distinct,” the concludes. “Instead, the United States should adopt a new approach that recognizes the inherent linkage between the two and fosters a healthier private maritime industry that can support U.S. national security.”

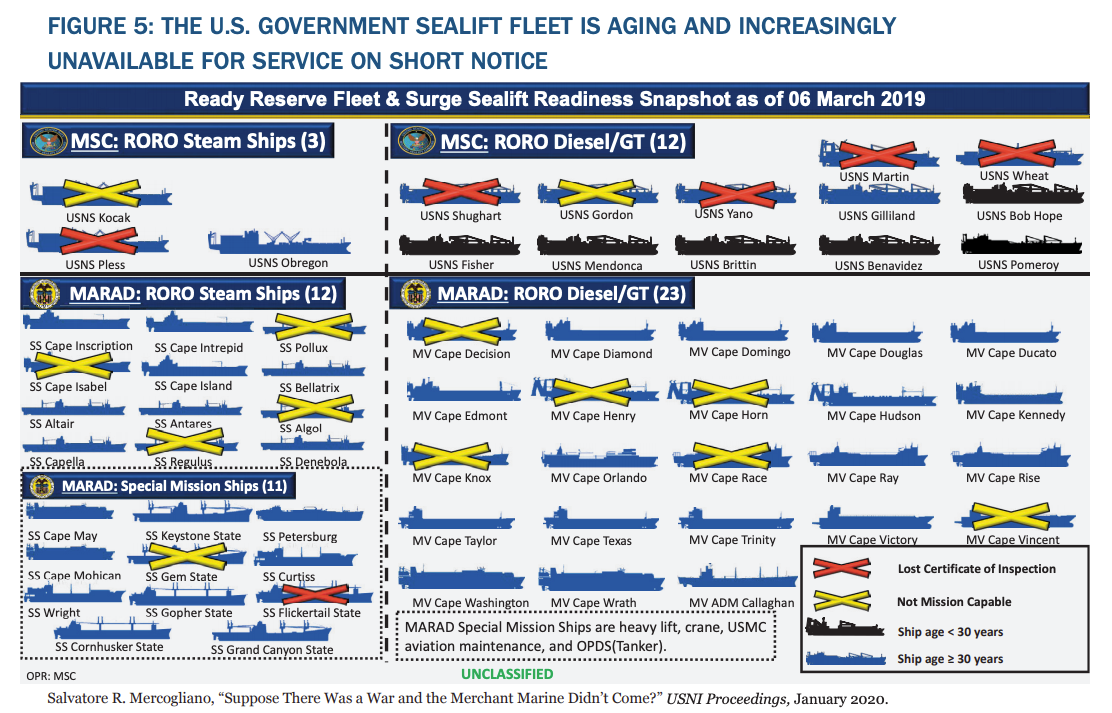

If the Pentagon were to mobilize a large expeditionary force quickly, the first wave of ships carrying equipment to theater would come from two sources – the 46 vessels in the U.S. Department of Transportation Maritime Administration (MARAD) Ready Reserve Force and the 15 vessels in the Military Sealift Command (MCS) surge fleet of fast sealift and large Medium-speed roll-on/roll-off ships.

U.S.-flagged commercial ships would then be hired by the Department of Defense to conduct sustainment sealift – the resupply of forces and gear to the theater. If needed, the Pentagon would also charter foreign-flagged ships to deliver supplies.

The Problem

The U.S. strategic sealift capability is facing a myriad of challenges, including an aging fleet comprised of ships in many cases more than three-decades-old, an aging workforce to crew the ships and work in the yards building and maintaining the fleet and insufficient numbers of vessels in the fleet. These problems have been forming for decades, without a unified strategy to address them, according to the report.

In September, the U.S. Transportation Command tested the ability of the nation’s maritime Ready Reserve Force to set sail on short notice. However, only about 40 percent of the vessels deemed ready to sail left port, according to retired Rear Adm. Mark Buzby, the administrator of MARAD. Buzby detailed the exercise during an appearance at the 2020 Surface Navy Association symposium.

Part of the problem, according to the CSBA report, is the U.S. Merchant Marine is short by about 2,000 mariners to properly crew ships if the MSC, MARAD and MCS Surge Sealift Fleets were all activated to deliver equipment and resupplies during a prolonged U.S. military engagement.

The fleet also doesn’t have enough ships to operate during a prolonged period. If all available MSC and MARAD ships were used, the report estimates the Pentagon would still need to charter about a half-million square feet of additional cargo capacity on either U.S. or foreign-flagged ships.

Part of the shortage is because the existing fleet is old. Part of the shortfall was caused by a decades-long decrease in the number of U.S.-flagged ships, caused by a combination of tax policy, competition against state-subsidized foreign shipping lines and changing global economics.

The Department of Defense’s fuel tanking capacity is even more dire, according to the report. The Pentagon has access to about 10 percent of the tankers needed to supply an overseas force. The Pentagon would need to hire 76 more fuel tankers to meet the anticipated demands of fueling a force.

“DoD’s sealift capacity gaps will likely only worsen. Most government sealift ships will need to be retired during the next decade, and DoD’s fuel requirement is expected to grow as military services adopt operational concepts that rely on distributed forces and maneuver to improve survivability and lethality,” according to the report. “The gap in cargo and tanker capacity will require either recapitalizing and expanding the MSC and MARAD surge sealift fleets or bringing more oceangoing commercial ships under U.S. flag.”

Solutions

The report’s authors call for establishing a national maritime strategy to address the various reasons why the nation’s sealift capacity is in such poor shape.

Already, the benefits of a unified strategy can be seen by looking to China, the report states. The Chinese government has invested heavily in building the People’s Liberation Army Navy, the Chinese Coast Guard, the People’s Maritime Militia, and heavily subsidized state-owned shipping companies. The result is the world’s largest government and commercial fleets. The Chinese government, through its Belt and Road Initiative, has also gained port access around the globe for commerce, logistics and naval operations.

“In contrast to China’s integrated maritime strategy, during the past few decades the United States has adopted a predominantly military strategy designed to synchronize missions and capability priorities between the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, but not at the whole-of-society level,” the report states.

The U.S. must expand participation in the Maritime Security Program – which provides U.S.-flagged ship operators with stipends to help defray the costs associated with being part of the U.S. sealift capability.

The U.S. needs to attract more people to become merchant mariners and to stabilize the workforce at shipyards.

U.S. officials should consider replacing the government-owned prepositioning fleet with MARAD-chartered commercial ships. The ships in the prepositioning fleet would then join the MSC surge fleet, which would be assigned to MARAD.

“The U.S. government can continue misallocating increasingly scarce funds on a flawed model. Or, guided by a new national maritime strategy, the nation can adopt a whole-of-society approach to cultivating a vibrant maritime industrial base that spurs innovation and enhances American prosperity and security,” the report concludes.