Ahead of next week’s release of a Fiscal Year 2021 budget request that is widely feared to cut Navy spending, a senior member of the Senate Armed Services Committee is proposing legislation that would protect shipbuilding plans.

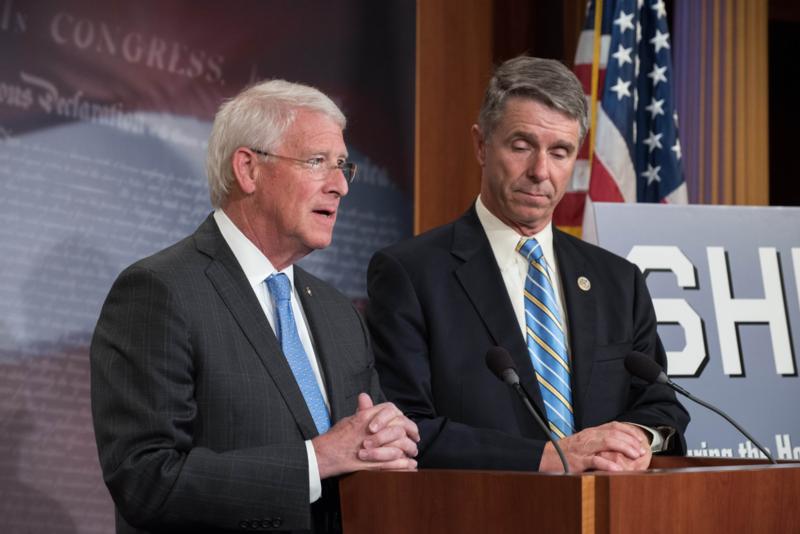

Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), who sponsored 2017 legislation that required the Navy to aim for a 355-ship fleet, today introduced the Securing the Homeland by Increasing our Power on the Seas (SHIPS) Implementation Act. It builds upon the previous SHIPS Act by authorizing a slew of authorities to help the Navy keep costs down and introduce new capabilities faster, as well as urging that the Pentagon and Congress actually put resources towards Navy plans to grow the service.

It adds a “sense of Congress” that a certain number of ships should be bought over the next five years. This language is basically a recommendation – “sense of Congress” language isn’t binding – but it asks the Navy to continue on the trajectory laid out in its most recent long-range shipbuilding plan.

The SHIPS Implementation Act asks the Navy to start construction on:

- 12 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers

- 10 Virginia-class submarines

- two Columbia-class submarines

- three San Antonio-class amphibious ships

- one LHA-class amphibious ship

- six John Lewis-class fleet oilers

- five guided-missile frigates, compared to plans to buy 10. A congressional aide familiar with the bill told USNI News that SASC was interested in taking a conservative approach to the new frigate program, planning for just one a year until a contractor is selected later this year and can prove that it can build a good ship for the Navy. The bill adds that “new guided missile frigate construction should increase to a rate of between two and four ships per year once design maturity and construction readiness permit,” which is an increase from the Navy’s current two-a-year plans and could be achieved by the Navy awarding a contract to a second shipyard to build the Navy-owned design.

While the SHIPS Implementation Act recommends buying mostly the same number of ships the Navy’s long-range ship plan calls for, USNI News understands that this legislation is meant to protect against any major cuts that the Office of the Secretary of Defense may try to make in the budget request. The aide said that, based on memos sent back and forth between the Pentagon and the Navy, the Navy could be facing 20-percent cuts to its shipbuilding budget over the next five years.

“Our nation’s Navy is still the envy of the world, but our adversaries are quickly catching up. It is time for Congress to get serious about investing in our fleet and give our sailors and Marines the tools they need to stay ahead of those who wish us harm,” Wicker said in a news release.

“In the near term, the SHIPS Implementation Act would empower our Navy to reach its 355-ship goal by authorizing the procurement of specific vessels and cutting costs. Over time, my proposal would help to decrease risk for the Navy and provide greater certainty for the industrial base.”

The aide added that reaching 355 ships is a matter of national policy, having been passed into law in 2017 as part of the FY 2018 National Defense Authorization Act. However, Navy topline spending isn’t even keeping up with inflation, and as the Navy struggles to pay for the manning and the maintenance it needs for today’s fleet of 293 ships, it’s not clear that there’s a path to pay for a fleet of 300 ships, let alone the 355 called for in law. The aide said the SHIPS Implementation Act is meant to be a conversation-starter between Congress, the White House, the Pentagon and the Navy to figure out how to responsibly get the Navy the money it needs to grow the fleet in accordance with rising maritime threats around the globe.

In his statement, Wicker noted the Navy – based on recent years’ spending levels – is about $4 to $5 billion short in spending each year to reach a 355-ship fleet in the near term. If the Pentagon’s request includes shipbuilding cuts, that delta would become even greater. The aide noted that the bill doesn’t specify where the money should come from – whether within the Defense Department budget or somewhere else – but simply says the Navy needs more money to pay for its expensive Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine program while also allowing the rest of its shipbuilding programs to grow, too.

The legislation calls for the Navy to reach 355 ships “as soon as practicable,” according to the news release. Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly has said he believes the Navy can get to 355 by 2030 – but those estimations are based on Navy plans and industry capacity, not the realities of funding that are requested by the Pentagon and approved by Congress, and therefore out of the Navy’s control. The Navy’s most recent long-range shipbuilding plan, which is supposed to be somewhat resource-informed, doesn’t show the service getting to 355 ships until 2034.

USNI News recently asked Modly why the Navy was struggling to get sufficient funding, if the National Defense Strategy that guides Pentagon-level spending and decisions is largely a maritime strategy.

“The Secretary of Defense has to balance all that with the demands from the Air Force; we’re creating a new Space Force; obviously the Army has a role in that theater and other theaters. So we’re just going through the process of understanding what does the joint warfighting scenario look like in there. We’re trying to make the case for a bigger Navy, and I will continue to make the case for a bigger Navy, but ultimately that comes down to Secretary (Mark) Esper and the president to determine whether or not he wants to shift dollars to make that happen more rapidly,” Modly said in a Jan. 31 phone interview.

“I told the Navy that we’re going to head out on that path (to accelerating shipbuilding to reach 355 ships by 2030) starting in 2022, and we’re going to drive towards getting to 355 by the end of the decade. I am completely convinced that there’s money within our budget that could be spent a lot more efficiently – I’m talking about just the Navy budget – and we have to do the work to do that before we can convince anybody else above us to give us more in our topline.”

In addition to setting a floor on shipbuilding quantities, the SHIPS Implementation Act would also “authorize the use of several cost-saving measures, including multi-year or block buy contract authorities when appropriate,” and “minimize risk for the Navy by requiring shipbuilding prototyping to occur at the subsystem-level in advance of ship design, to the maximum extent practicable.”

Specifically, the legislation would allow the Navy to enter into a multiyear contract for an America-class amphibious assault ship and three San Antonio-class LPD Flight II ships – something that was never done for the Flight I LPDs built at Ingalls Shipbuilding in Wicker’s home state of Mississippi – as well as up to six John Lewis-class oilers and two Columbia-class subs. The aide told USNI News that, in addition to saving about eight to 10 percent per hull through multiyear procurement contracts, the emphasis on having multiyear contracts for all mature ship classes would provide further stability and predictability to industry.