When a sniper platoon needed a bunch of caps to protect the spotting scopes of their high-dollar, highly-calibrated rifles, a small team of Marines aboard amphibious warship USS John P. Murtha (LPD-26) got to work.

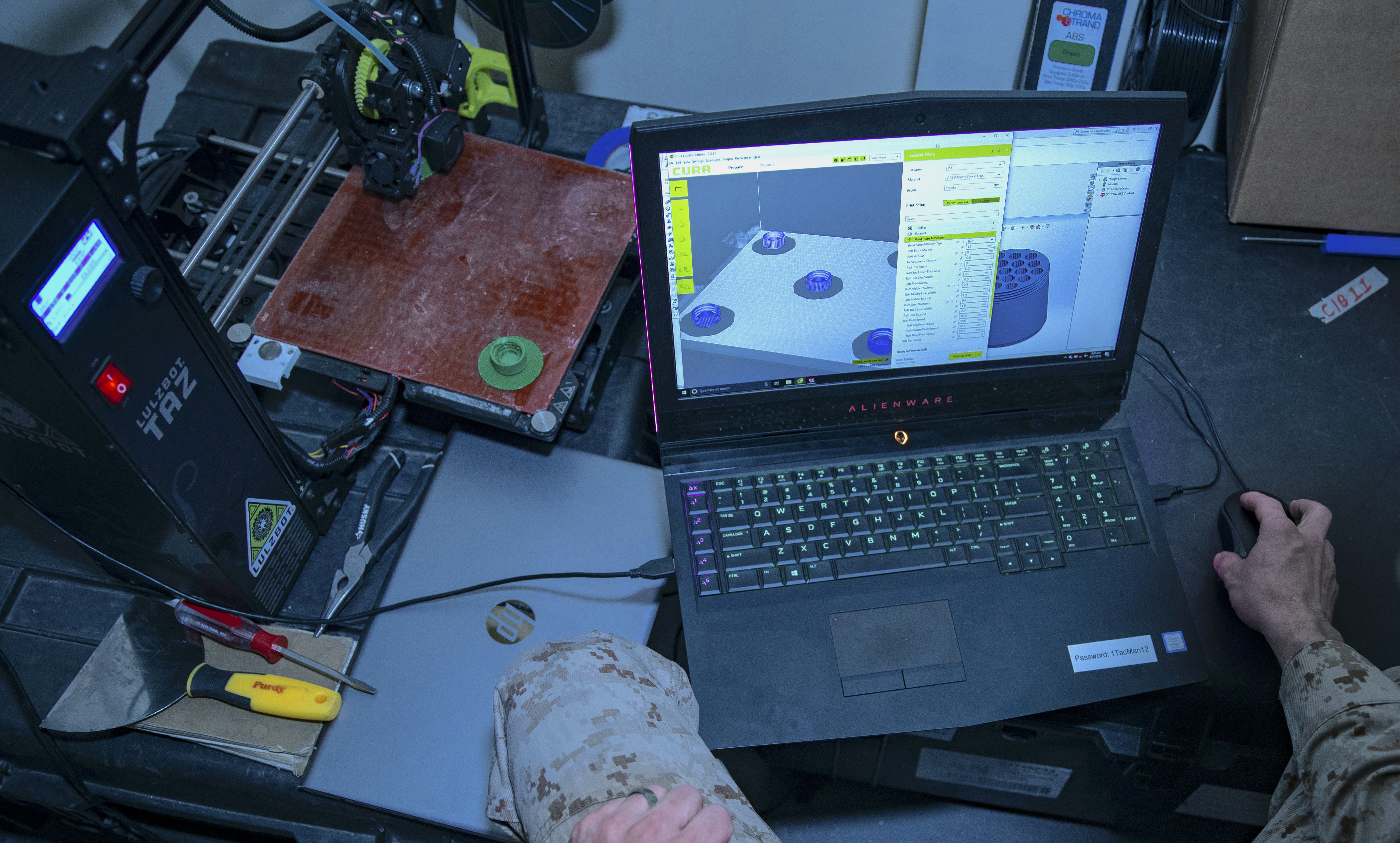

Using a portable 3D printer, laptop computer and spools of plastic filament, the Marines with Combat Logistics Team 11 fabricated caps that were exact replicas, down to the markings and brand design. It took hours to create the caps from the green sourcing material that were then painted camouflage to match the rifles used by Weapons Company’s sniper teams with the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit.

But that time spent making the caps was far less that what may have been weeks to get replacement caps from their home base at Camp Pendleton, Calif., or through the Marine Corps’ supply chain since the 11th MEU was deployed overseas with the Boxer Amphibious Ready Group.

While the caps aren’t big-ticket items, they are critical to the effectiveness of the snipers and to ensure their weapons are protected and remain in prime, pristine condition whether the platoon operates teams at sea or ashore.

“You’d want no sand clinging to the lens,” Chief Warrant Officer 3 Kyle Hanson, CLB-11 maintenance officer, told USNI News by phone from amphibious assault ship USS Boxer (LHD-4). The snipers “appreciated every cap that we gave them.”

The 11th MEU and Murtha just offloaded with San Diego-based Boxer, dock landing ship USS Harpers Ferry (LSD-49) and Amphibious Squadron 5 following a liberty port stop in Hawaii. The 11th MEU/Boxer ARG is wrapping up a deployment to the Middle East and Western Pacific that began in May.

Along with typical stocks of spare parts, gear and equipment, the 11th MEU deployed with a Tactical Fabrication (TACFAB) 3-D printing kit that gives it the ability to print fully-functional parts as well as molds or prototypes.

CLB-11’s team of Marines used computer-aided design software to build replacement or repair components with the 3-D printers on Murtha and Boxer. The process of additive manufacturing, or AM, creates items from material stocks, such as spools of plastic filament heated and melted into specific shapes to create each component. The idea behind additive manufacturing and TACFAB is for military units to make those items and have that needed part in hand much faster than getting it through the traditional and longer supply chain, especially when out at sea. It can be cheaper, too.

“The printer was able to save a lot of time and make it so that an important piece of equipment could be ‘kept in the fight,’” Capt. James Stenger, the 11th MEU spokesman, told USNI News eariler this month as the unit stopped in Hawaii en route home to Southern California.

The 3D printing capability supported the MEU/ARG throughout its deployment as it conducted distributed operations, said Maj. Andrew Kettner, CLB-11 executive officer, speaking by phone from Boxer. The team aboard Murtha created some 30 items that would have cost $4,851, according to a MEU synopsis. “It’s so incredibly cost-effective,” Kettner said.

“It’s exciting to see nothing become something,” he said. “It’s a good feeling to see that Marine’s excitement for what they just made. They did it as a team – two or three people – on a ship somewhere out in the ocean, far away from the supply chain.”

Hanson and his team, which included Staff Sgt. Brandon Ballentyne and Sgt. Tyler Foster, worked from Murtha and Boxer, and fabricators also were on the Harpers Ferry.

With TACFAB, the design team created many small but critical parts for MEU Marines that often are easily damaged or lost. Among them: Trigger guards. Windage adjustment cover for a combat optic. Caps for water jugs. SIM card tray for by an Iridium satellite radio. Adapter arm for a GoPro helmet-mounted camera. Mounting bracket for a mini-laser finder. Rotating fiber-optic retention ring. Side access covers and weather seals for PRC-153 radios. SABER/TOW missile lens cover. A container for blasting caps. Honeycomb filters for a rifle combat optic scope.

They even made tiny clamps that aren’t available through procurement and an S-bracket to hold a mirror in a berthing space.

While still an emerging capability, the TACFAB is part of the Marine Corps’ broader push to innovate logistics and use additive manufacturing to give small, expeditionary units deployed away from the supply chain something of a self-supporting resupply capability. The capability is important when deployed and traveling on ship. “Because the rear-base support is minimal… it was ultimately going to be on us – the design team – to create whatever requirement is within our means,” Hanson said.

TACFAB had a big impact, especially in helping keep the MEU’s high-use equipment like radios in good working condition. It took just nine minutes for a Marine aboard Murtha to create a tiny locking mechanism in the power connector insulator assembly to fix a VRC-110 Sim J27 multiband radio. The tiny spacer ensured wires won’t touch and render the radio unusable.

“So what deadlined this vehicle radio was no longer” a problem, Kettner said. It may have taken “weeks, if not more, to get the replacement part from the States,” he added. “It cost 7 cents” to make from the sourcing material, he noted, for a savings of $2,122.93.

The TACFAB system, packed into a portable, hardened case, is easily mobile for front-line units or smaller, deployed logistics teams to create items up to 14 inches by 14 inches in size. It’s smaller than large, 3-D printers the Marine Corps has in the transportable, five-ton X-FAB, or Expeditionary Fabrication, shelter where Marines can make larger components with various materials to include metal for heavy-equipment items.

TACFAB printing is limited by size, Hanson said. It won’t be used to build components that are under high stress or require certain military specifications. But CLB-11 partnered with sailors in the machine and fabrication shop aboard Boxer, which has a lathe and 3D capability to support the amphibious ready group, to create some components or build molds for parts fabricated from metal it couldn’t do with TACFAB. The Marines had worked with the shipboard sailors during predeployment exercises, Hanson noted, so that “only made working through problems that much easier.”

The technology and the training continue to advance and grow as more design teams experiment with and get more experienced in using and designing items to build. It takes some science know-how, also, to figure out the tensile strength of polymers to ensure durability. “The more the Marine Corps employs 3-D teams at the tactical level, the greater the education,” Hanson said. “Every day is a new page written,” he added, “because we don’t know when items are going to break.”

The 11th MEU didn’t deploy 3D printers off ship during the deployment, but components created went ashore with battalion landing team Marines including during a summer exercise in Kuwait. The high-summer temperatures in the Middle East region didn’t reveal any heat-related failures among 3-D printed parts, Hanson said. Nor did cold, snowy training exercises at the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center in Bridgeport, Calif., a year earlier.

CLB-11 will submit formal lessons learned during the deployment and will share the experience with CLB-13 and CLB-15, the other two Camp Pendleton-based logistics units that support West Coast MEUs, Kettner said. “The sky’s the limit,” Hanson added. “We’re always trying to look for ideas.”

Last year, the 26th MEU was the first sea-going unit to deploy with 3D printing capability. Among the items the team created: miniature ships for terrain models used by operational planners. The 31st MEU also took the 3D capability to sea that spring, creating, among other items, a bumper for a landing gear door on an F-35B Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter.