ANNAPOLIS, Md. – The Navy is gaining enough experience with unmanned vehicles on and below the water’s surface that it’s becoming easier to kick off new programs, as each can build on previous program’s lessons learned, service officials said last week.

On larger unmanned surface vessels, the Navy and Pentagon’s Ghost Fleet Overlord program transitioned from Phase 1 to Phase 2 at the beginning of October, further building upon the base of knowledge that will inform two future programs of record, the Large Unmanned Surface Vehicle (LUSV) and Medium USV (MUSV).

Howard Berkof, the deputy program manager for unmanned maritime systems within the Program Executive Office for Unmanned and Small Combatants (PEO USC), said Phase 1 wrapped up with the successful demonstration of two vessels that had been outfitted with autonomy systems for unmanned operations.

“We’ve completed over 600 hours of autonomous testing, we’ve demonstrated autonomy, we’ve demonstrated navigation, and we’ve launched into the Phase 2 with our two vendors now,” Berkof said last week at the National Defense Industrial Association’s annual Expeditionary Warfare Conference.

After his speech, he told USNI News that “Phase 2, we integrate a government [command, control, communications, computers and intelligence] system into the vessel, we do more complex autonomy, more complex navigation, and we start also some payload work. And then so we get through Phase 2, and then we will have a number of demonstrations out there where we really ramp up the capability on that front.”

Once the integration of a government C4I system onto a hull rigged to operate autonomously is complete, the only real remaining work will be to add in a vertical launching system to give the USV a strike capability.

“For the Navy’s LUSV program, we envision integrating vertical launch into that vessel. … That’s really the biggest difference” between Ghost Fleet Overlord Phase 2 and LUSV, Berkof said.

The Navy released a solicitation for conceptual design of the LUSV in early September, and proposals will be coming back within the next month or so, he said during his panel presentation.

Even as the Navy is bringing this research project into a program of record, the Marine Corps is eyeing starting its own USV acquisition effort.

Earlier in the conference, Lt. Gen. Eric Smith, the deputy commandant of the Marine Corps for combat development and integration, described his vision for the use of a long-range USV.

“If you can produce something that is a thousand-mile vessel, that’s truly autonomous, that can carry the cargo that I need to sustain myself. And so I lose it – this goes back to, I don’t want to be efficient, I want to be effective; if the vessel itself is cheap enough that I can put three of them out there, and I just need one of them to get to me, well that’s terribly inefficient, but it’s super effective because we’re going to do cost-imposition. And if you’re the adversary, well I guess you’re going to need to target all three,” the general said.

“So I hope you bought enough DF-XXs [Chinese anti-ship weapons] because I’m going to try to spread you out. That I don’t mind saying publicly. So long-range unmanned surface vessels, for us, vitally important because they’re lethal. They’re not just connectors; they’re sniffers, they’re out there telling me what’s going on, they’re passing that information back to me, and they’re spreading out the enemy because at some point you’ve got to target everything that moves because the one thing that does get through is carrying the lethal package” to help the Marines achieve their aims.

Though the Marine Corps has a definite interest in using USVs, the service doesn’t have a written requirement or an acquisition plan yet. Berkof said his program office has been working closely with several Marine Corps entities as they work through what they might want to buy.

“We’re trying to get aligned, understand what they want to do. They’re still figuring out their requirements, and we’re supporting them. We don’t know exactly what they’re going to buy yet or how they’re going to buy it; we’re supporting them, we’re giving them a lot of information on our systems like the [mine countermeasures] USV but also our market research, stuff that we’ve learned,” he told USNI News after his presentation.

“We’ve had very candid conversations of, hey, here’s what we’ve learned, here’s what we can and can’t do, giving them as much information as possible. That dialogue will continue and we’ll see where it ends up; we’ll see where the requirements end up and we’ll see how they wind up acquiring the systems.”

Berkof said the LR-USV the Marines want may be closer in size to the Navy’s Mine Countermeasures USV (MCM USV), or Textron’s Common USV (CUSV) that will run payloads such as mine-hunting and mine-sweeping gear.

The Navy’s MUSV and LUSV will use a common C4I system. The MCM USV, however, uses one that is common to the unmanned systems within the Littoral Combat Ship mission package portfolio. That system, called the Multi-Vehicle Communications System, runs on the LCS ships or could be brought onto other ships or ashore facilities in a conex box and used to control the vehicles.

Berkof said it wasn’t clear yet what the Marines’ plan was for command and control of their LR-USV.

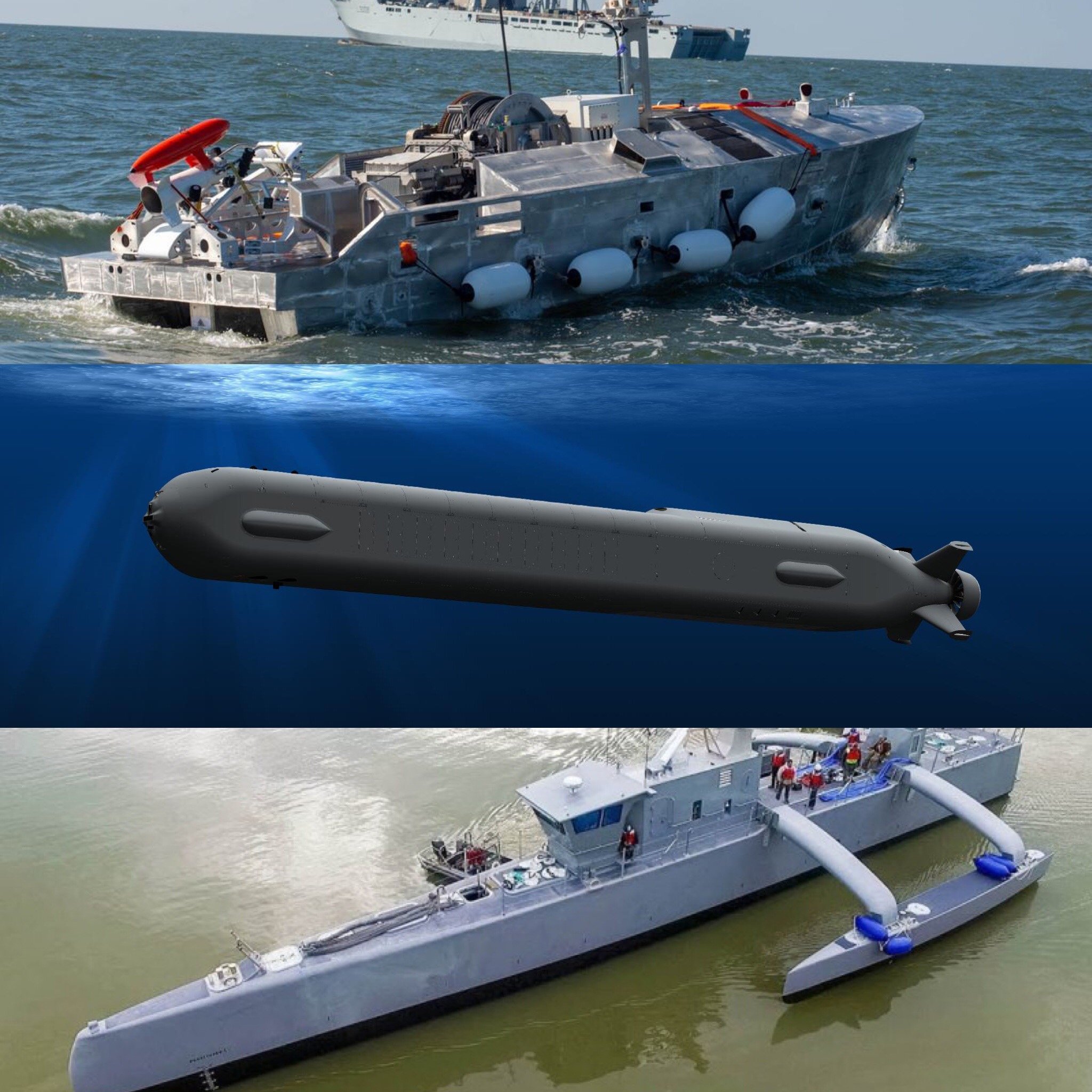

On the undersea side, the Navy is taking its expertise in two medium-sized unmanned underwater vehicles and combining them into a single program.

The Razorback UUV is run out of Berkof’s PMS 406. The Mk 18 Mod 2 UUV that Expeditionary Mine Countermeasures (ExMCM) companies use is run out of the Expeditionary Missions program office (PMS 408).

“The Medium UUV is going towards a common vehicle: one vehicle that can be deployed from a submarine – the Razorback – or from a surface craft for expeditionary warfare purposes, which is the Mk 18 program,” Berkof told reporters after his presentation.

He said the one vehicle design would be able to be deployed from the surface or under the water and would accommodate different plug-in payloads for different mission sets such as mine countermeasures and intelligence preparation of the operating environment (IPOE) and sensing.

Berkof said the Navy posted a synopsis about a month and a half ago and should release a draft request for proposals soon. An industry day likely in late November will communicate to contractors what the acquisition strategy is and what the Navy thinks it wants to buy to meld the two existing programs.

In addition to PMS 406 and PMS 406, Berkof said the Program Executive Office for Submarines has been a great help in this effort, sharing lessons on integrating UUVs with submarines for launch and recovery and support.

“For torpedo tube-launched, that is a significantly big capability. There are two pieces to that: launching it is easy, recovering it is hard, so we’re working through that technology,” he said.

“And also integrating batteries, specifically lithium-ion batteries, for the submarine” is a challenge, Berkof added, but he said PEO Subs has already begun to work that safety problem through the Snakehead Large UUV program and has some lessons learned to apply to the MUUV effort.