ANNAPOLIS, Md. – The Commandant’s Planning Guidance has sparked several questions about the future of the amphibious ship fleet – how many ships are needed, and what kinds of ships will have a role in the future – and while answers are still in development, the expeditionary warfare community has a lot of thoughts on the matter.

During the National Defense Industrial Association’s annual Expeditionary Warfare Conference last week, several panels and speakers addressed the idea of what comes next for the mix of ships in the amphibious fleet.

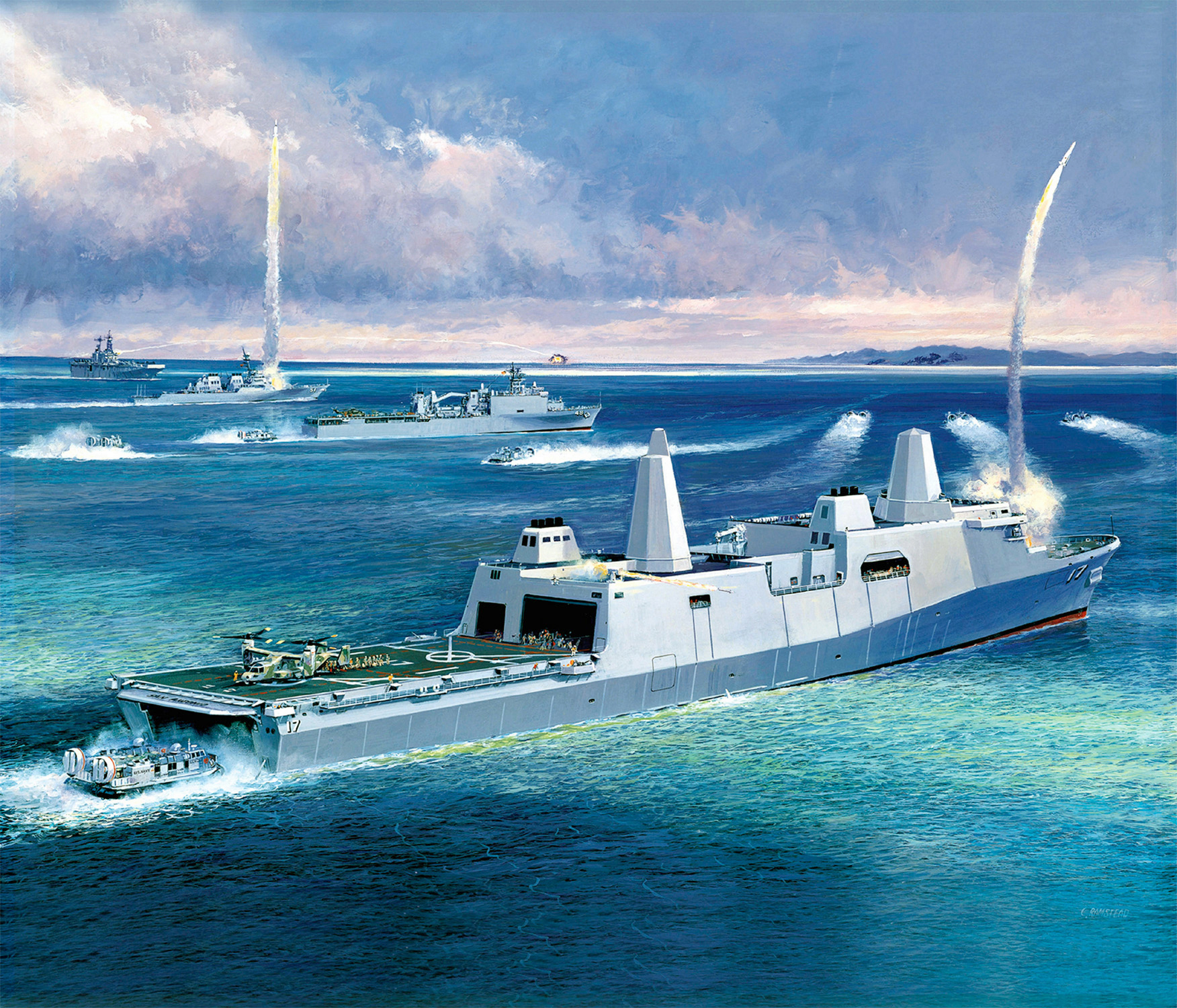

Capt. J.R. Hill, the amphibious warfare branch head within the expeditionary warfare directorate (OPNAV N953), said the Commandant’s Planning Guidance discusses adding a new capability to supplement the current amphibious ships. The two services are happy with the America-class amphibious assault ships and San Antonio-class amphibious transport docks as ship designs that will support their operations now and into the future. But the service is also looking at something smaller than today’s Whidbey Island-class dock landing ship (LSD-41/49) but larger than a landing craft utility (LCU) to complement the America and San Antonio classes.

Hill said OPNAV N95 and the two service headquarters are already working on top-level requirements for this new type of ship or craft, and the surface warfare directorate (OPNAV N96) and the fleet readiness and logistics directorate (OPNAV N4) are also involved in the effort.

Capt. Brian Metcalf, the San Antonio-class program manager, said during the same panel that he can’t do anything until he gets that requirement from the Navy and Marine Corps.

“I can keep building LPDs, or I can stop building LPDs and build something else, or build a different mix of an amphibious fleet size. But in order for me to design the solution set and get it on contract, I have to know what the problem is,” he said.

“If the problem is ships are too expensive, I can design you a cheap ship, but that may not be able to accomplish the mission. If you tell me what you’re trying to connect, what you’re trying to carry – am I carrying people or am I carrying tanks? Do I have to have a flight deck? Do I have to have a well deck? What is the self-defense system and concept of ops? That’s where the conversation starts, and I guarantee you NAVSEA can find a solution set that meets those criteria.”

Though funding for his LPDs are potentially at risk in this re-examination of the future amphibious fleet force design, Metcalf seemed open to new ideas about what the future fleet mix would look like.

The captain asked the audience to close their eyes and picture an Amphibious Ready Group; he then asked how many people pictured one LPD, one LSD and one LHA.

“We have defined, unfortunately, the ARG as a combination of one each of those three ships for entirely too long. Now, what if I could describe to you an amphibious readiness group that was an LPD with four [Littoral Combat Ships]? Two of them outfitted with mine packages, two of them with surface-to-surface weapons? Does that sound like an amphibious readiness group? It’s not the traditional definition, but could it go do amphibious missions? Two [Landing Craft Air Cushions] on the back of an LPD, with four LCSs. Does that sound like something a [combatant commander] might look for, that could accomplish a mission?”

Mark Rios, the NDIA Expeditionary Warfare Conference chair and a retired naval officer with experience in amphibious and mine warfare, pushed back on that idea, saying it was a “small task-organized force” but wasn’t sufficient to carry the Marine Expeditionary Unit typically embarked on an ARG.

Maj. Gen. Tracy King, the expeditionary warfare director (OPNAV N95), said in response that “ARGs and MEUs are for steady-state operations: it’s to assure allies, it’s for training, its to show the flag, it’s to respond to [humanitarian assistance and disaster relief missions]. It’s not to fight. We don’t fight ARGs.”

King noted that LCSs are fast, and are much more lethal now that the Naval Strike Missile is being added to the hulls. Further, he noted, an amphib is a warship and must be able to fight other warships, and to that end he suggested adding the Naval Strike Missile to amphibious ships as well. Previously the idea of adding Vertical Launching System cells to the LPDs had been debated but is largely viewed as unattainable in this budget environment.

“Do we need something like a Naval Strike Missile so the composite warfare commander calling on the cruiser, calling on the DDG-51, can use that magazine? Absolutely. And we’re going to try to do that, but it is a budgetary fight,” King said.

The budget fight – even as the Marine Corps wants to see its current amphibs made more capable and see the addition of a new kind of ship or craft to supplement today’s fleet – is still a bit unclear. King noted that the shipbuilding budget is tight and that to get something new you must get rid of something already in the plans. He said he’s still not sure what to get rid of to free up more money.

“I hear some commentary about, hey, let’s get rid of all of our L-class ships” to pay for the new alternate ship being proposed.

“Well, we can’t do it without our L-class ships. So is there a preferred mix? I think there probably is a mix. We still need the L-class platforms – for those of you who have ever been around an LPD-17 or deployed on it, it is a magnificent platform. If you’ve got an LPD-17 offshore, you can do whatever you need to do: you can do humanitarian relief, you can make water, you can provide food, and you can fight. So it is the utility infielder of the fleet; we can’t get rid of that just because we want something else. So what are we going to give up? I’m not sure yet.”

Under a “think exercise” explained by Congressional Budget Office senior analyst for naval weapons and forces Eric Labs, some LPD funding would be diverted to pay for the alternate ship. Labs made clear this was not a recommendation but rather an exercise to show what other kinds of fleets could be bought for the same money.

Under the long-range shipbuilding plan today, the Navy over the next 30 years would buy eight America-class LHAs and 20 San Antonio-class LPDs, which gives it a force of 37 ships in 2040 and just 35 in 2049. This current plan comes with a $75 billion price tag.

Under a new plan that diverts some LPD funding and invests in ships that cost $600 million to $700 million apiece, that same $75 billion could instead buy the eight LHAs and 60 to 70 alternate ships. That would create a force of 57 to 61 ships in 2040 and 83 to 93 ships by 2049.

Labs said the $600 million figure is more than an Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF) and more than an LCS but less than an amphib. What that alternate ship looks like is unclear, but it could be a modified EPF with greater range, it could be a Landing Ship, Tank (LST) connector that is modified to support other missions beyond tank transport ashore, or it could be a commercial ship modified to support the movement of Marines from ship to shore and island to island.

Other speakers during the conference kicked around other ideas; John Berry, the director of the concepts branch at the Marine Corps’ Combat Development and Integration directorate, suggested something akin to an Australian stern landing ship or a Danish Absalon-class support ship.

While many speakers focused on this new alternate amphib ship, one was highly focused on how to modernize or adjust today’s LPDs and LHAs to better support operations. Rear Adm. Cedric Pringle, who until recently commanded Expeditionary Strike Group 3 and now serves as the commandant of the National War College, is focused on how today’s ships can be better optimized for the fight he sees coming.

For example, Pringle said during the conference, “how do we actually get the LPD-17-class ship to give fuel to some of the smaller ships that are operating in the littorals? So right now the LCS, the Mk-6, all of the EPFs, as well as a lot of other assets that are being developed at speed; we have a lot of great assets that are coming online – the expeditionary staging base, the expeditionary staging dock – all of those assets will operate in the same battle space as our amphibious ships, who are already there, who are already delivering Marines to the mission set, who are already providing that command and control,” he described.

“Why not have that integrated command and control? Why not figure out how to have the ships integrated, so that when the smaller ships need a drink of gas, so to speak, they don’t have to go to the big-deck amphib, which currently is the only ship that can give fuel?”

He said he had the chance to speak to students at the Naval Postgraduate School in California during the course of his last assignment, and he told them he wanted to see thesis papers on these kinds of topics. Another he gave as an example is how to update today’s steam-powered amphibious assault ships to include more modern hybrid propulsion systems that reduce operations and maintenance costs: would it be better to backfit the hybrid propulsion system onto existing ships, or build new ones to replace them ahead of the end of their service lives?

“My personal opinion is, it’s probably cheaper to build a new ship from the keel up, because that gives you that foundation of technology that you can then build upon. And to me – and I’m biased, having commanded Makin Island,” which is the first hybrid propulsion drive amphib that runs on electric auxiliary propulsion motors at low speeds and gas turbines at higher speeds.

“I think that as we start looking at directed energy weapons systems and some of those things, we have to look at the underpinnings for those systems as well. And Makin Island has a high-voltage electrical system; why can’t we have something similar to that on future ships?”