WASHINGTON, D.C. – The Navy won’t pursue the development of a lethal carrier-based unmanned aircraft before it fields its unmanned MQ-25A Stingray tanker sometime in the 2020s, the service’s requirements chief said last week.

The service is taking a deliberate approach to adding unmanned aviation assets to carrier decks, ensuring it successfully integrates the MQ-25A into the airwing before it studies adding new, armed UAVs into the mix, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Systems (OPNAV N9) Vice Adm. Bill Merz said at an event co-hosted by the U.S. Naval Institute and the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“The MQ-25, we think, is just a fantastic program. Integrating an unmanned aircraft into the carrier airwing will be a significant step forward for the Navy, no question about it,” he said.

“We are just compelled to be somewhat pragmatic in how well they work before we over-commit. We have a limited budget; we also have real lives at stake. Unmanned isn’t really unmanned, you just don’t have a body sitting in the platform. There’s a lot of support. You have deck handling, a lot of things you have to come through to bring these things aboard a maritime environment.”

In August, Boeing was awarded an $805-million contract to develop four MQ-25As. The company based the design on a prototype the company quietly built for the canceled Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) competition.

Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson has made fielding the MQ-25A a priority for the service, but it’s still unclear how quickly the service can get the capability to the fleet, Program Executive Officer for Unmanned Aviation and Strike Weapons Rear Adm. Brian Corey said earlier this month.

“When we awarded our contract [in August], we believed we could go to 2024, [but] CNO said ASAP,” Corey said. “I’m not going to give you a date. It’s as soon as we can.”

The Navy wants to introduce the aircraft quickly to reduce the refueling burden on the service’s F/A-18F Super Hornet fighter that are now responsible for the tanking mission. Based on the success of the first set of missions – tanking and limited intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) missions – the Navy could look to other capabilities.

“It’s a big aircraft, it’s robust, it’s built as a tanker, but it’s probably a stepping-stone to other capabilities,” Merz said.

“[Future aircraft] are conceptual right now until we get this thing into the fleet and see how it survives in a sea environment and how it integrates with the airwing.”

However, at least one analyst sees the Navy’s progress in unmanned vehicles as a missed opportunity for the service.

“Yes, the MQ-25 is a stepping-stone. However, the Navy had an opportunity to develop and field a more robust unmanned capability for surveillance and strike and chose not to do so, at least not in the mid-term,” said Mark Gunzinger with Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. “A carrier-based low observable [Naval Unmanned Combat Air System] for surveillance, strike and possibly other missions was identified as a need at least as far back as the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review. Over time, this has been scaled back to the MQ-25. I’m not saying the MQ-25 is not needed, but I do believe the Navy has missed an opportunity.”

Based on the 2006 QDR, the Navy developed a low observable, potentially armed $1.4-billion demonstrator program. The service tested a UCAS-D aircraft, two X-47Bs – Salty Dog 501 and 502 – built by Northrop Grumman to prove unmanned aircraft could safely launch and be recovered from an aircraft carrier. The tail-less aircraft were built with the ability to be refueled mid-flight and had an internal payload capability equivalent to an F-35C Lightning II Joint Fighter.

In 2013, Salty Dog 502 successfully landed on USS George H.W. Bush (CVN-77), after aerial refueling tests in 2015, Naval Air Systems Command shut down the testing program for UCAS-D with thousands of hours of flight time left on the airframes – to some congressional protest.

“Our nation has made a sizable investment in this demonstration program to date, and both air vehicles have consumed only a small fraction of their approved flying hours,” Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz) wrote in 2015.

“There will be no unmanned air vehicles operating from carrier decks for several years. I think this would be a lost learning opportunity in what promises to be a critical area for sustaining the long-term operational and strategic relevance of the aircraft carrier.”

At the time, the Navy said additional testing with the X-47Bs would be cost-prohibitive given the shift in the service’s focus to an unmanned aircraft that would not need to operate in heavily contested airspace.

“The Navy chose to pursue the MQ-25 and not fund a capability that would, frankly, be of greater utility in a great power conflict,” Gunzinger said.

However, the Navy is rethinking the future of its airwing as the U.S. positions itself into a new era of great power competition.

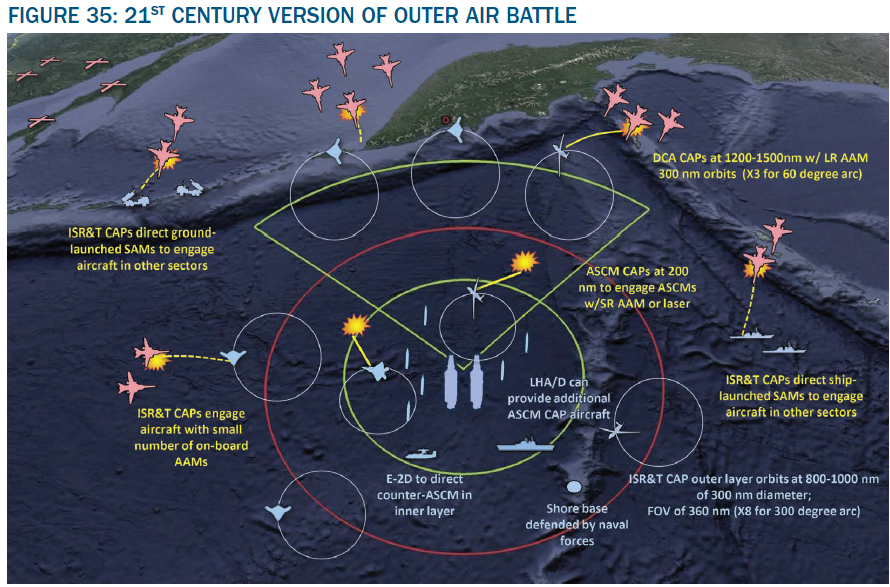

A CSBA study Regaining the High Ground at Sea: Transforming the U.S. Navy’s Carrier Air Wing for Great Power Competition called for a new carrier-based unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAV) to allow a standoff distance of 1,000 nautical miles from threats.

That standoff distance is far beyond the Navy’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornet’s effective combat range of 450 nautical miles and the emerging F-35C’s range of 600 nautical miles.

“You have an airwing of aircraft that are relatively short range but relatively high payload, but that’s not necessarily well suited to these [long distance] operations,” CSBA report author Bryan Clark said earlier this year.

Clark’s conclusions for a new UCAV for the service echo internal Navy conversations about the future of the airwing, USNI News understands.

Navy officials have backed away from a clear time horizon for the follow-on to MQ-25A.

“We’re very excited about it, and we’re leaning into it as hard as practical,” Merz said.