The former commander of USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) is pushing back against a rebuke from the Secretary of the Navy, disputing major facts in the service’s argument he was criminally negligent leading up a June 17, 2017, fatal collision, according to a copy of the April 26 rebuttal obtained by USNI News.

Earlier this month, Richard V. Spencer wrote that former Fitzgerald commander Cmdr. Bryce Benson failure to prepare his crew and maintain his ship led to the collision with the merchant ACX Crystal off the coast of Japan, killing seven sailors. Benson sustained injuries himself when his stateroom was crushed by the flared bow of the ship, and he had to be rescued by his crew.

“For the entirety of the time you served as the Fitzgerald Commanding Officer, you abrogated your responsibility to prepare your ship and crew for their assigned mission. Instead, you fostered a command characterized by complacency, lack of procedural compliance, weak system knowledge, and a dangerous level of informality,” Spencer wrote in his two-page letter dated April 9. The Navy issued the censure to Benson and the tactical action officer on duty during the collision, Lt. Natalie Combs, in lieu of a court-martial over negligence charges.

In his 18-page Friday rebuttal, Benson lays out what would have been the spine of his case if it had made it to court-martial.

“I am rightly held to account for every action aboard my ship that night, from the performance of my watchstanders to my crew’s heroic efforts to save a sinking ship while I was incapacitated by injury,” wrote Benson. “I reflect on the tragedy, mourn for the lives of my sailors, and pray for the grieving family members and my crew every day. Yet the conclusions … that my leadership was ineffective, my judgment poor, and my responsibility for my sailors’ deaths unequivocal—derive from factual errors and allegations unsupported by evidence. They deserve a considered response, both for my record and for the Navy’s effort to become a true learning organization.”

Specifically, Spencer divided Benson’s failings into to broad categories informed by the prosecutions arguments and Navy criminal charging documents: decisions made immediately before the collision and longer-term decisions he made from when he took command about a month before the collision.

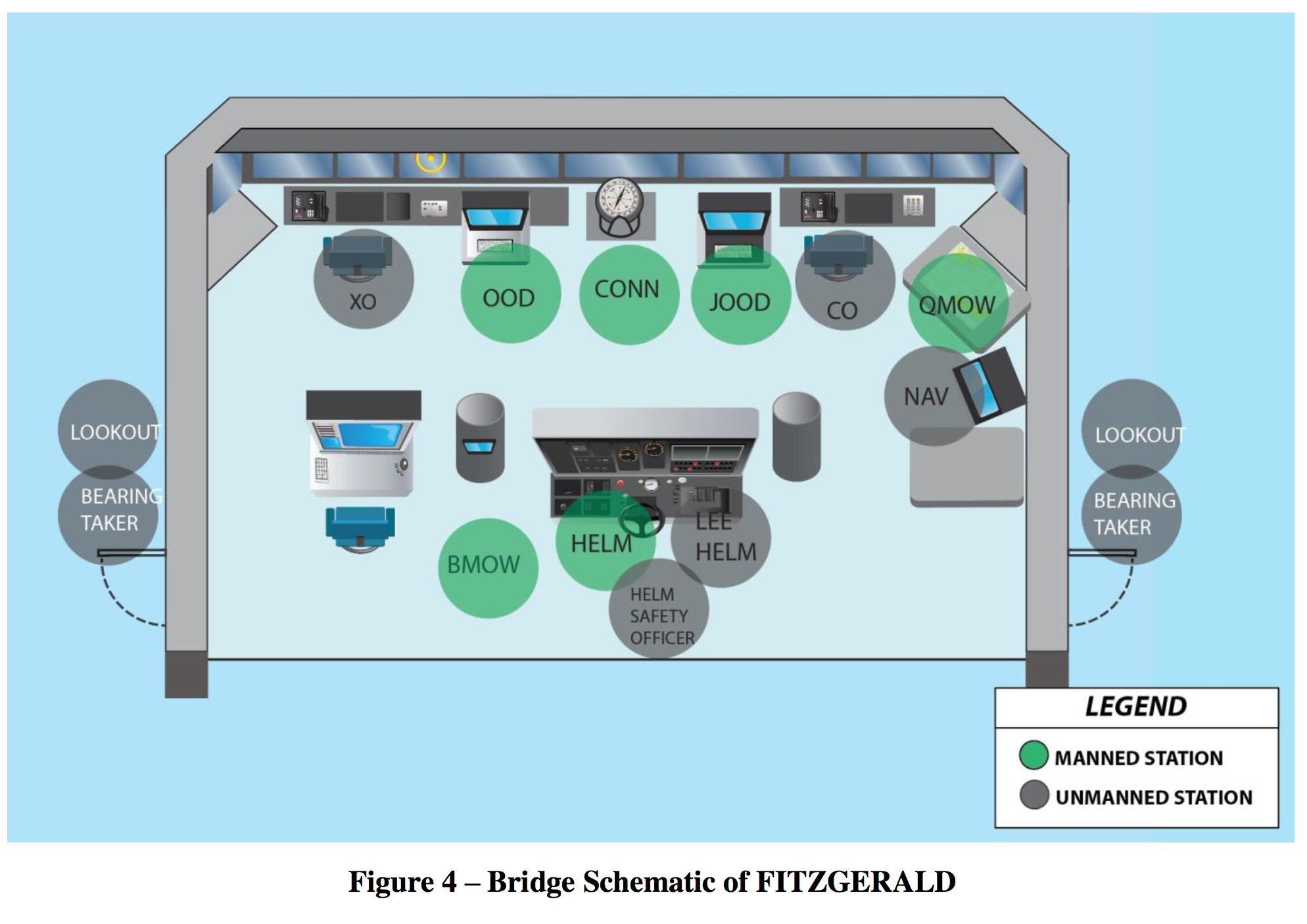

In the hours before, Benson had assigned an “inexperienced watch team,” was “disengaged and removed from the tactical control and supervision of the ship,” and “fail[ed] to implement any mitigation measures, such as ordering the Executive Officer or Navigator to supervise the team on the bridge,” Spencer wrote.

On the day before the collision, Spencer wrote, Benson had failed to approve an adequate watch bill, didn’t revise standing orders to account for degraded equipment and had laid out a navigation plan that had Fitzgerald travel too fast too close to shore.

In his rebuttal, Benson argued that his ship and crew were as ready as could be expected given the stresses his crew was under to meet the demands of a no-notice mission from the highest levels of the Pentagon after another destroyer in the squadron was unexpectedly sidelined.

In the letter to Spencer, Benson outlined a dense operational schedule that began shortly after the ship left a maintenance availability in January of 2017 with a crew that had seen 40-percent turnover and little time to train or conduct maintenance on the ship.

The mission came 10 days after Fitzgerald had suffered an engine fire as part of a group underway during an unexpected four-month deployment and had to return to Yokosuka, Japan, for emergent repairs.

Specifically, Fitzgerald had been scrambled by U.S. 7th Fleet to replace USS Stethem (DDG-63) at the last minute for a national tasking in the South China Sea.

“In the case of getting FTZ underway on 16 June 2017 to swap FTZ for STE, there were no other [courses of action]; FTZ was the only ship available,” former Destroyer Squadron 15 commander Capt. Jeffery Bennett told investigators, according to the rebuttal.

Several defense officials over the last several weeks confirmed to USNI News that the sidelined Stethem had suffered a malfunction to its vertical launch system that made the ship undeployable.

According to two defense officials familiar with the operation, the national-level tasking assigned at last minute to Fitzgerald was a South China Sea freedom of navigation operation that was aimed at contesting Chinese regional claims.

Benson argued against the declaration of his incompetence, saying the crew of Fitzgerald had performed well under the time crunch required for the last-minute mission, citing several successful training events after leaving Yokosuka.

“I say without reservation: 16 June was the best day that I had at sea during my then-eighteen years of service. I had no basis—fatigue or otherwise—to request an amended schedule and postpone our training certifications or delay or forego our national tasking in the South China Sea,” he wrote. “Likewise, at the end of this day, I had no doubt that my watch team could safely navigate a straight-line transit through unrestricted waters.”

Benson also contested that his crew was satisfied with degraded equipment, citing several instances when the sailors aboard worked to fix dozens of material deficiencies in the periods they had to work on the ship. He also contested the assertion in the censure that his navigation track was poor and his watch team was inexperienced.

“Each had been qualified by at least one previous commanding officer. In January 2017, Destroyer Squadron 15 certified our crew, after assessing our watchbills and watchstanders’ level of knowledge; our navigation equipment certification followed shortly thereafter,” Benson wrote. “I too had assessed, based on direct observation and Fitzgerald successful operational schedule in 2017, that each of these watchstanders was capable of safely and effectively manning their watches in accordance with applicable Navy orders and my standing orders.”

The point-by-point refutation of the censure outlines the heart of Benson’s legal argument: though the watch team misjudged the risk posed by Crystal, the operational realities in 7th Fleet shaped the situation and the mistakes didn’t rise to the level of criminal negligence.

To that point, Benson quoted from the Comprehensive Review that was written after the collision of Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) by then-U.S. Fleet Forces commander Adm. Phil Davidson

“[T]he FDNF-J force generation model could not keep up with the rising operational demands for cruisers and destroyers in the Western Pacific. 2016 was the tipping point for the combined FDNF-J force generation, obligation and force employment demand. Rapidly rising operational demands and an increase in urgent[] or dynamic tasking led to an unpredictable schedule and inability to support training and certification,” wrote Davidson. “There was an inability of higher headquarters to establish prioritization of competing operational demands.”

Still, in his letter Benson doesn’t offer an explanation for what specifically went wrong when the collision occurred.

“I was responsible for evaluating Fitzgerald operational risks and mitigating them to the point of acceptability. Throughout this rebuttal, I have described the process by which I attempted to fulfill that responsibility. I did not accurately foresee the risk of my watch team’s breakdown in communications, teamwork, and situational awareness, and so manifestly I did not take sufficient action to manage that risk,” Benson wrote.

“My responsibility for risk-management was unique, but it was not singular… All levels of the Navy are responsible for evaluating, communicating, and mitigating risk. And the Navy also demands that risk decisions be made ‘at the appropriate level,’ which ‘is the person who can make decisions to eliminate or minimize the hazard, implement controls to reduce the risk, or accept the risk’.”

A spokesman for Secretary of the Navy acknowledged a Friday USNI News request for comment on the rebuttal but did not immediately provide a response.