ARLINGTON, Va. – The Navy has stood up a program office within its Strategic Systems Programs (SSP) to address the conventional prompt global strike mission the Pentagon has handed to the sea service, the SSP director said recently.

Vice Adm. Johnny Wolfe, speaking earlier this month at the annual Naval Submarine League symposium, said each service will field some sort of hypersonic capability to contribute to conventional prompt global strike – the idea that the military should be able to hit any target on the planet within about an hour. The Navy is developing the hypersonic glide body that all the services will use, as well as a booster to launch the Navy’s weapon off a yet-to-be-determined platform.

To support this development, the Pentagon and Navy acquisition officials have agreed on an acquisition decision memorandum for the new hypersonic capability and asked Wolfe to set up a program office specifically for that system.

“We have a program, we are funded, and we’re moving forward with that capability, which is going to be tremendous to allow our Navy to continue to have the access they need, whether it be from submarines or from surface ships,” he said.

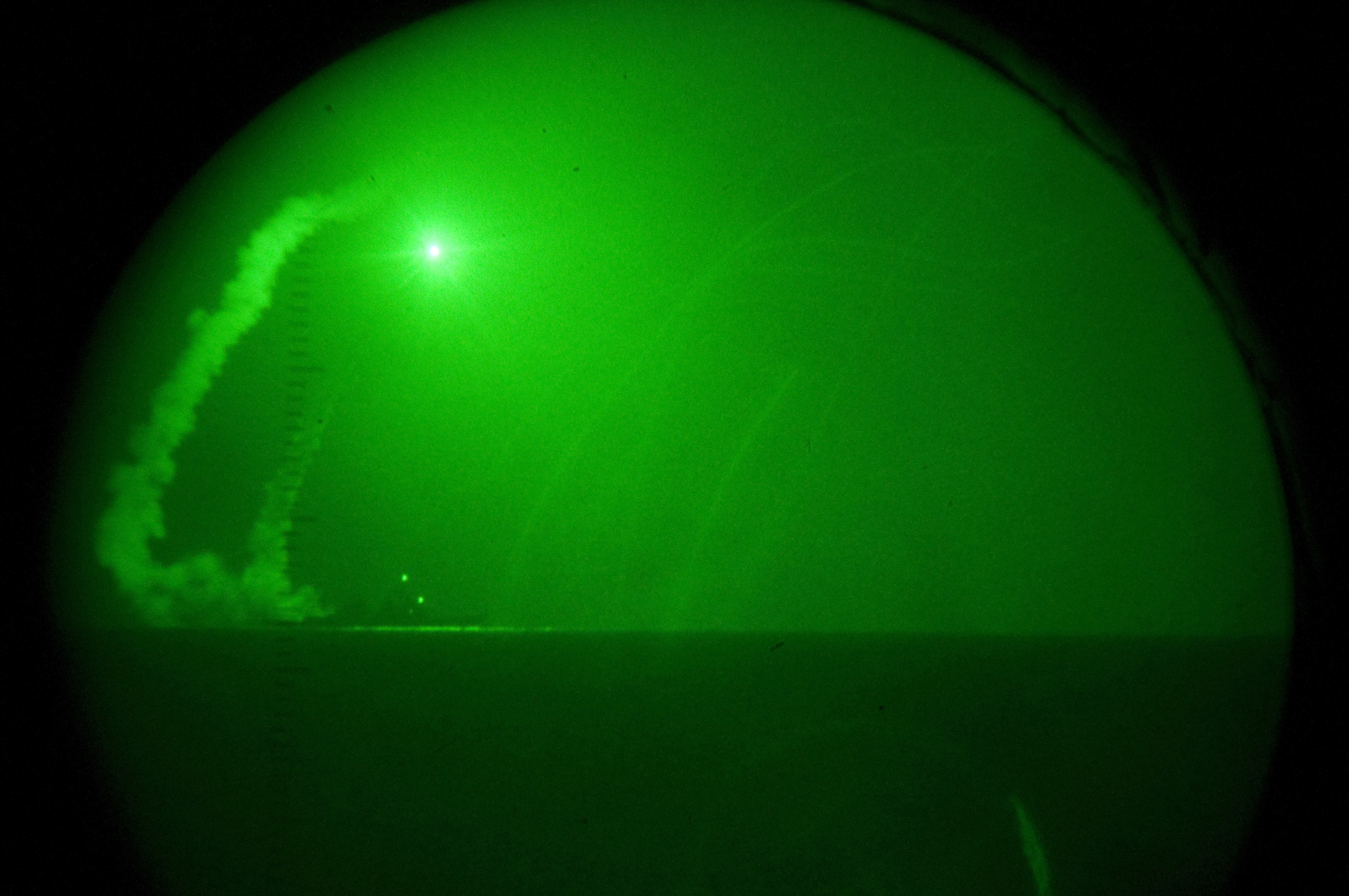

That open question – whether a sub or a surface ship will launch the weapon – is a new development. At last year’s Sub League event, Wolfe’s predecessor, Vice Adm. Terry Benedict, announced that SSP had flown a weapon from a ground-based test site in Hawaii that could eventually support the conventional prompt global strike mission from an Ohio-class guided-missile submarine (SSGN) tube.

This year, Wolfe said the Navy is intentionally keeping its options open as it develops the glide body and the booster.

“We’re developing the cone hypersonic glide body that will not just be for the Navy, it will be for all the services as they figure out what platform they want to go deploy a capability like this on,” he said in response to a question from USNI News during his presentation.

“From a Navy perspective, we’re developing the booster that our hypersonic glide body will go on, and we’re doing it though in such a way that we’re taking the most stringent requirement – which is underwater launch – and so as we develop it we will do it in such a way that as the bigger Navy comes through what platform or platforms they actually want to deploy this on, the launcher and the glide body will be able to survive any of those environments.”

The decision to put the weapon on a submarine, a destroyer or another platform would come from higher up in the Navy chain of command, but “the key is, we will start with the most stringent requirement, we will build the missile and the glide body to that, so that as we look at how we’re going to do it we don’t have to go back and do a bunch of redesign.”

Another new mission set SSP has been given from the Pentagon is developing a low-yield nuclear weapon that the Trump Administration requested in response to Russian weapon development.

In collaboration with the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), SSP was given funding at the start of this fiscal year to develop and field a small number of “76-2” low-yield weapons, which “will be a direct counter to what Russia believes they’ve got to date that we do not have,” Wolfe said.

“We will have that capability in direct response to Russia.”

The admiral said it was a testament to the original W76 nuclear warhead program, which began in the 1970s, that it was agile enough to take on this new mission set on a short timeline.

Asked about creating a new weapon despite a U.S. ban on testing nukes, Wolfe said, “the way we’re doing this, at the unclassified level – we just about tested everything that we need to test at one point or another for that program (W76), which is what gives us the confidence that when we go to do these, the system will work. We don’t need to go do a test with this; we’ve got all the right models from all the years of operating the 76 and the 76-1 which we’re deploying now.”

“We are 100-percent confident that when we put those out there, they’re going to work as designed,” he added.

Much like the W76 remaining agile enough to keep up with today’s changing needs, Wolfe also spoke of the Trident D5 missile – the sub-launched ballistic missile that can carry the W76 warhead – and its need to keep up with changing needs.

The Navy has already done one life extension (LE) program to modernize these missiles, but “we’re going to physically run out of Trident D5 missiles. We bought an inventory of 533, we are no longer producing the equipment section, we are no longer producing post-boost. So we have to go build more missiles” so they can equip the upcoming Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The Trident missile was bought for the Ohio-class SSBN, but each year the Navy tests a certain number of missiles to ensure their continued reliability, and due to that testing the number of missiles is slowly dwindling.

In what is being called Trident D5 LE2, Wolfe said the Navy would pursue a hybrid of a life extension and a new program – keeping some components, like the rocket motors that are still in production today, while investing in new avionics and other front-end items for the missile.

“The motors, like I showed you, they’re going to stay the same because if you think about it, tube diameter’s the same, the height’s the same, and there’s other requirement for me to go to. So that’s going to stay the same. But then all of the front-end stuff, the equipment section, the electronics, that will all be new,” Wolfe told USNI News after his speech.

The admiral said that many details still had to be worked out in upcoming studies, such as how many missiles to buy, how much of the new technology could be backfit onto today’s existing missiles, what industrial base capacity exists to build these missiles, if new manufacturing techniques like additive manufacturing could be leveraged to create efficiencies, and more.

Ultimately, Wolfe said, the Columbia-class subs will have fewer missile tubes than the Ohio class because of the proven reliability of the Trident D5 missiles, so SSP has to create a new missile for the duration of the Columbia program – through 2084 – that is as reliable or better.

The “secret sauce” to doing that, he said, is building in flexibility so that components prone to obsolescence – the avionics, guidance, post-boost system, primary battery and more – can be easily upgraded down the road as technology evolves.