The next five years of fleet training and testing in the Pacific waters off Hawaii and Southern California might affect marine life but shouldn’t have permanent, lasting harm to marine mammals, sea turtles and other sea life, the Navy concludes in a voluminous environmental document released last week.

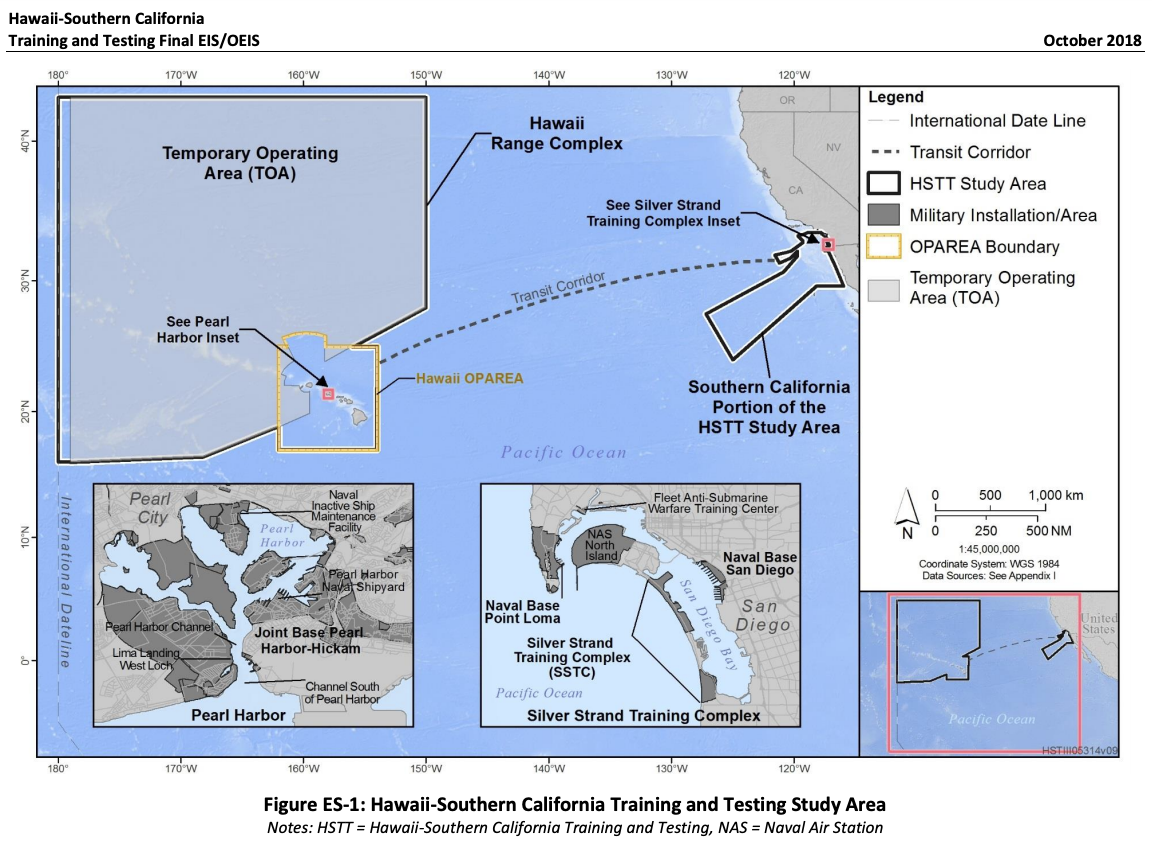

On Friday the service submitted a Final Environmental Impact Statement, totaling more than 4,000 pages of documents detailing and analyzing potential environmental impacts from training, testing and other activity in the Navy’s ranges, an area known collectively as the Hawaii-Southern California Training and Testing study area, or HSTT.

The Navy is asking the National Marine Fisheries Service for another five-year permit to conduct military training and testing that officials acknowledge would harm marine life, to an extent, even with mitigation measures meant to lessen those impacts. The service is required to complete an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS, that analyzes environmental impacts from various alternatives of activities, along with a “no action” scenario, as the National Environmental Policy Act requires before it can get federal authority to use the critical ranges. The existing permit runs through December.

“This updated analysis will support future activities beginning in late 2018,” the Navy said Friday in announcing the completion of the Final and Overseas EIS. Publication and public availability of the EIS starts the 30-day waiting period before the Navy issues a record of decision.

The Navy wants to continue to train units, as well as conduct research, development, testing and evaluation in the study area, which encompasses vast sea, air and undersea ranges and Navy harbors and piers in and around Hawaii and Southern California. So with the eye on the next five years, at least, the federal O.K. would enable the Navy, “into the reasonably foreseeable future, as necessary to meet current and future readiness requirements.” That would accommodate changes in the fleet and force structure, such as additions of new weapons or autonomous systems.

The Navy cites the growing need to train crews in realistic situations using passive and active sonar, by ship and by air. It plans to use active sonar and explosives at sea, off the coasts of Hawaii and Southern California. Sonar is used to detect and locate mines and enemy submarines, the latter which officials say are getting harder to find because of quieter, noise-reducing technologies used by countries including China and potential rogue threats.

But the Navy’s use of sonar and underwater explosives has come under fire by environmental conservation groups that have sued the Navy for harming marine mammals. Three years ago, a federal judge ordered the Navy to implement some temporary restrictions on training and ship transits, in line with its 2013-2018 permit. Those limitations don’t carry through into the new permit, however.

Loud noise from military training and operations at sea including sonar, air guns or explosives can affect marine life and interfere with normal behaviors. The use of certain types of sonar have been blamed for the deaths, injuries and strandings of marine mammals such as whales and dolphins.

Under the proposed preferred plan is “a net increase in testing systems that use sonar and a net decrease for explosives use.”

The Navy admitted that training and testing activities in its “preferred alternative” will stress marine populations but contended those impacts would be reduced with mitigation, such as trained lookouts on Navy vessels and powering down active sonar and scheduling to ease those stressors.

“The aggregate impacts of past, present, and other reasonably foreseeable future actions continue to have significant impacts on some marine mammal species in the Study Area. The Proposed Action could contribute incremental stressors to individuals, which would both further compound effects on a given individual already experiencing stress and, in turn, have the potential to further stress populations, some of which may already be in significant decline or in the midst of stabilization and recovery,” officials wrote in the Final EIS executive summary. “However, with the implementation of standard operating procedures reducing the likelihood of overlap in time and space with other stressors and the implementation of mitigation measures reducing the likelihood of impacts, the incremental stressors anticipated from the Proposed Action are not anticipated to be significant.”

“Marine mammals and sea turtles are the primary resources of concern for cumulative impacts analysis,” officials added, “but the Proposed Action is not anticipated to meaningfully contribute to the decline of these populations or affect the stabilization and recovery… The aggregate impacts of past, present, and other reasonably foreseeable future actions have resulted in significant impacts on some marine mammal and all sea turtle species in the Study Area; however, the decline of these species is chiefly attributable to other stressors in the environment, including the synergistic effect of by-catch, entanglement, vessel traffic, ocean pollution, and coastal zone development.”

The Final EIS downplays the likelihood of any lasting, permanent injuries due to training and testing on marine-life populations. “Exposures to sound-producing activities presents risks to marine mammals that could include temporary or permanent hearing threshold shift, auditory masking, physiological stress, or behavioral responses,” the report states. “Individual animals would typically only experience a small number of behavioral responses or temporary hearing threshold shifts per year due to exposure to acoustic stressors, and these are very unlikely to lead to any costs or long-term consequences for individuals or populations.”

But environmental groups that have dogged the Navy over its sonar use might disagree with the Navy’s optimism and believe the latest EIS falls short in protecting marine mammals.

“While the Navy is planning activities that will increase harm to whales since the last round of approvals, it is also whittling down mitigation that is currently in place. I’d like to see the military protecting our natural heritage by avoiding harm to marine mammals,” said Miyoko Sakashita, senior counsel and oceans director at the Center for Biological Diversity, which joined in the 2015 lawsuit against the NMFS and Navy.

The Navy warned what would happen if the fisheries service doesn’t grant the permit.

“Cessation of proposed Navy at-sea training and testing activities would mean that the Navy would not meet its statutory requirements and would be unable to properly defend itself and the United States from enemy forces, unable to successfully detect enemy submarines, and unable to effectively use its weapons systems or defensive countermeasures,” officials wrote in the executive summary. “Navy personnel would essentially not be taught how to use Navy systems in any realistic scenario. For example, sonar proficiency, which is a complex and perishable skill, requires regular, hands-on training in realistic and diverse conditions.

“In order to detect and counter hostile submarines, the Navy uses both passive and active sonar. Inability to train with active sonar would result in no or greatly diminished anti-submarine warfare capability,” the Navy said.

For the 2018 EIS, the Navy took a different approach from its 2013 report in how it analyzed expected training activities, including the use of sonar, and the impact on marine mammals. Officials concluded the service had overestimated the amount of sonar use and corrected some classification of explosives by basing annual maximum training projections on the certification processes for eight carrier strike groups, far more than done in actuality. So the Final EIS details a reduction in estimated sonar use during unit-level exercises, with 600 hours of hull-mounted mid-frequency sonar expected during a COMPTUEX rather than the 1,000 hours originally assumed in the calculations, according to the document. Overall, hull-mounted sonar projected over the next five-year period would amount to just half the amount of sonar used during the 2013-2018 permit period.

Driving the Navy’s latest permit application is the “focus on live training to meet evolving surface warfare challenges,” officials stated. “This results in a proposed increase in levels of Air-to-Surface Warfare activities and an increased reliance on the use of non-explosive and explosive rockets, missiles, and bombs.”

The Navy plans eight Sinking Exercises (SINKEX) in the next five years, a significant drop from the 40 analyzed for the 2013-2018 period, according to the document. Also, officials expect a maximum of three Composite Unit Training Exercises (COMPTUEX) each year or at most 12 in any five-year period. It plans to increase the training in maritime security operations – these include drug interdiction and anti-piracy operations – in Southern California.