ABOARD USS IWO JIMA, OFF THE COAST OF ICELAND – Today’s sailors and Marines have grown proficient at operating in the heat and sands of the Middle East, but the bitter cold and jagged lava rocks of Iceland in October is a new challenge to most of them.

The U.S. military has placed a renewed importance on Europe, and Northern Europe in particular– a geography that a much smaller number of today’s sailors and Marines have first-hand experience in. U.S. Navy and Marine Corps officials acknowledge they have a lot to learn about operating in that part of the world, and they hope the ongoing Trident Juncture 2018 NATO exercise will help highlight areas that need improvement.

Rather than launching Marines ashore on the glassy waters of the Persian Gulf, the challenge for the naval team will be to a sail a three-ship amphibious ready group into a Norwegian fjord, launch helicopters for an air assault in the swirling winds the fjords can create, launch amphibious connectors to bring Marines ashore over the small islands and rocks of the Nordic archipelago, and then operate ashore for several days in the frigid weather.

Ahead of the live exercise in Norway, which runs Oct. 25 through Nov. 7, U.S. naval forces planned rehearsals to practice in the cold weather by themselves before linking up with 31 NATO allies and partners. The Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group and embarked Marines from the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit planned to conduct an amphibious landing and an air raid in Iceland that was observed by USNI News.

“The Marines have operated in an environment over the last 20 years, since 9/11, with their boots in the sand in places like Afghanistan and Iraq. It’s great to come to a place like Iceland or Norway, operate in an archipelago, in a place that is a volcanic landscape, that is hard ground, difficult ground to navigate over – and do it in cold weather. So a ton of lessons learned there,” Adm. James Foggo, the head of U.S. Naval Forces Europe and commander of NATO Joint Force Command Naples, told USNI News in an Oct. 16 interview in Reykjavik, Iceland.

“Additionally, the North Atlantic and the high north is a very unforgiving environment in blue water. USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) is out there right now. We haven’t operated a carrier in that vicinity since the late 1980s. … What are we learning? We’re doing flight ops in cold weather. We’re doing flight ops in high seas. We’re having to make the call – is it safe? Can we continue? Can we recover aircraft? And there’s one last thing that is a very valuable lesson learned, and that is communications, connectivity and interoperability with allies. So high north, again, difficult environment to maintain seamless connectivity, so we’ve got to learn how to work around that. And we have all these allies and partners that are out there with us with slight variations in their communications suite that we’re trying to make interoperable through our Link 16 and through our comms suites.”

24th MEU Operations Officer Lt. Col. Chris Niedziocha told USNI News on Oct. 17 aboard USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7) that he joined the Marine Corps in 1997 and shortly afterward conducted his first overseas exercise in Norway. Though the Marine Corps still has that gear from two decades ago, the Navy and Marine Corps now have to re-learn how to use that gear, how to do their jobs in thick winter clothing, how to time operations to take into account the slower pace of movement in the cold weather, and more.

“Even simple things like, do we have enough boots? Do we have enough white camouflage?” he said.

“It’s a matter of breaking out systems that we haven’t used – like an LCAC (landing craft air cushion), you use certain heater systems to prevent ice from forming on it. So it’s just not a planning factor that you’re used to dealing with – okay, I need to leave a six-foot alleyway on the side of the craft (for the heaters), and whereas normally I can put – I’m speaking in generalities – 10 vehicles on it, in this environment I can put seven.”

Niedziocha said operating in this high north environment affected his planning in many ways.

“In cold weather, everything just takes a little longer. Even something as simple as starting up an aircraft when it’s 10 (degrees) below, it just takes a lot more time. It’s not so much lift or capacity, it’s just time,” he said.

“With surface craft like LCACs and AAVs (amphibious assault vehicles) the real issue is, where we’re used to operating in 5th Fleet, not a lot of sea state, not a lot of weather, long periods of daylight – here, here at the high north in the wintertime, daylight’s very short; sea state 5, 6, 7; [modified surf index], the conditions at the beach – so the conditions are just harder here. … The other challenge we found is just logistically we’re not used to operating in the high north, so we had to rethink some about how our logistics are laid out.”

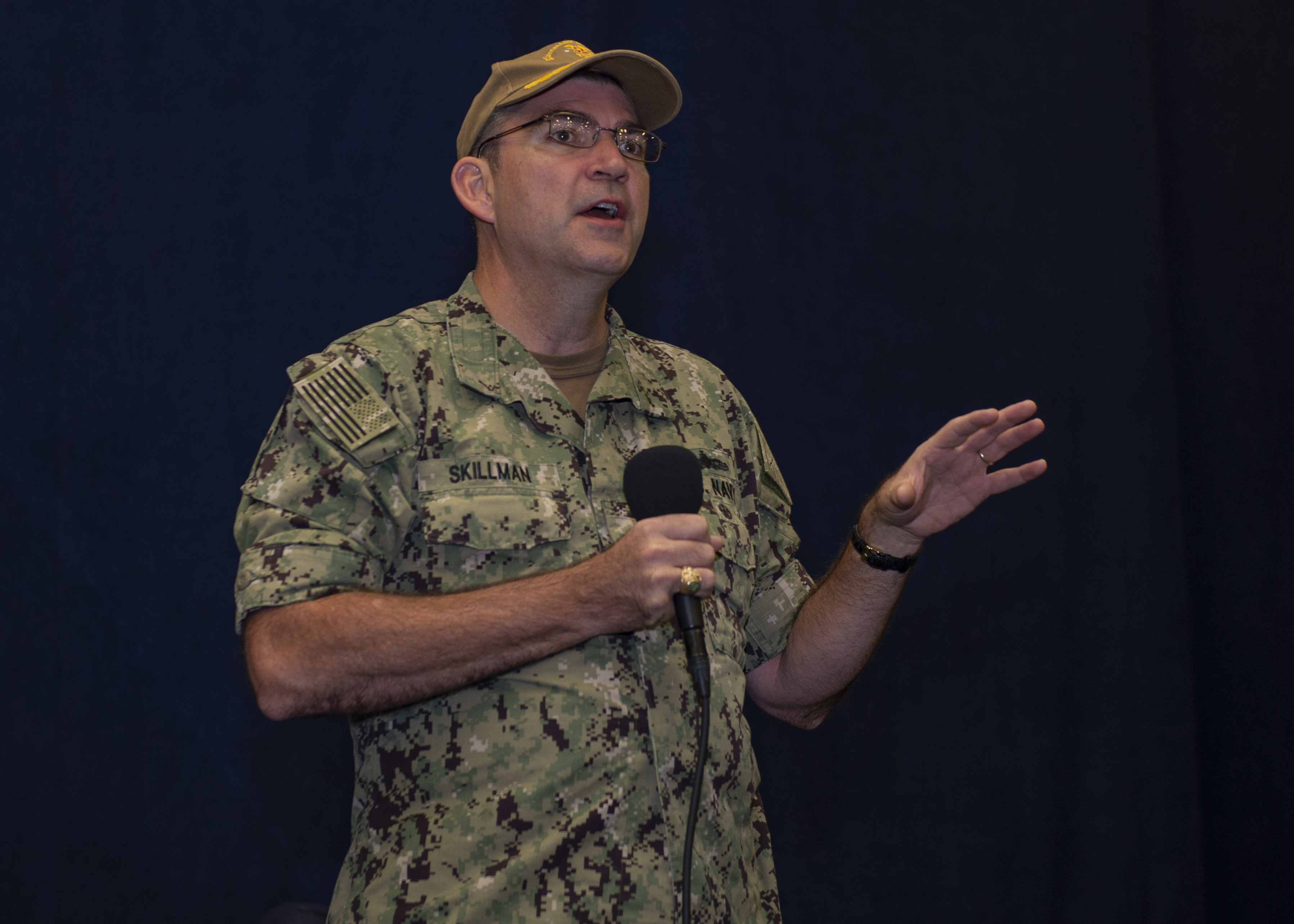

Rear Adm. Brad Skillman, commander of Expeditionary Strike Group 2, told USNI News aboard Iwo Jima that the cold weather and heavy seas forced the ships’ crews and the embarked Marines to re-think how they went about every task at hand, including chaining down vehicles and tools and securing items in work and living spaces to keep everyone and everything safe during transit.

“One of the things I really talked about with Iwo Jima in particular was, we’re used to operating in warm-weather climates where we do all of our maintenance up on the flight deck on the aircraft. Well now we need to move them down into the hangar and do the maintenance. … move them down, do the maintenance, move them back up, because it’s rough and it’s cold and it’s hard,” Skillman said.

“For the sailors, they’re having to now put on multiple layers, we have rain gear that they need to wear. When they’re on the flight deck and it’s really windy, we talk about safety and making sure that we have lifelines around the edges and nets to keep people on, but make sure they’re standing in the center of the ship as much as possible, have good footing and just pay attention to that. That also goes into, understand that the pace of operations is not the same. Take is slower, take it easier, make sure that you’re safe and understand what’s going on. Bring people in to warm up – we usually have to bring people in to cool off because it’s so hot, now we have to bring people in to warm up. So that’s what we’ve been focused on.”

All of these challenges left leadership with a conundrum in Iceland, though: they needed to practice in the cold weather and heavy seas because they lack experience, but the lack of experience made the training event all the more dangerous. The ARG arrived in Iceland a bit behind schedule due to rough seas and taking a less direct path to avoid even rougher seas. And ultimately the Oct. 17 amphibious landing on Iceland was canceled, not due to the weather but due to dangerous surf conditions along the rocky coast. Marines were still able to come ashore once the amphibious ships pulled into port and conduct cold-weather training on land later in the week. Several officials told USNI News that they wanted to gain realistic cold-weather experience for their sailors and Marines, but since this was an exercise and not an actual conflict, they weren’t willing to take too much risk with the amphibious landing.

“This is not war, there is not an imperative that I do something right now today,” Skillman said.

“Pace of operations are very important, especially in cold, wet weather operations, so we’re going to take it very safe, try to get our objectives done, and the lesson we’re going to identify at least is, it’s difficult to operate in cold weather in the high north.”

Niedziocha added “risk management is a big part of (preparing for Trident Juncture); you want to prepare people to operate in a really unforgiving environment. Obviously, this is an exercise, so the goal is not to hurt or kill anybody or damage any important expensive piece of equipment, so I took a very deliberative approach to that and tried to stair-step up in levels of difficulty. So we did training back in North Carolina, cold weather classes, read after-action reports, talked to people who have been there, made great use of our Norwegian [liaison officers] to explain how to operate in this environment. Now we’re coming here to Iceland where it’s a little bit harder but still not as hard, and then the next stair-step up in intensity is being in Norway, where it is going to be very cold, people are going to be ashore for a number of days.”

Skillman said this first major foray into Nordic operations would shape plans for future exercises in the region, giving military leaders a more realistic feel for the U.S. forces’ ability to operate there and at what pace.

“I think that’s going to be a huge lesson we’re going to have to learn. In an exercise like this, you build an exercise out and it’s on paper and it’s a plan. So you’ll have, I want to do this planned exercise event at this day and this time, I want to do the next one two hours later, and the next one two hours later. Well what happens if you have high winds or heavy seas that day? You have to decide whether you want to pick up and move it to another day or you just want to cancel it,” he said.

“So it’s going to be very interesting to see what actually can you expect to accomplish in the time at sea in the North Atlantic in end of October, early November.”

For Niedziocha, he said he was looking forward to returning to the training area where he first started his career, as well as reengaging with allies and partners.

“I was last in Norway in 1997, so I’m excited to get back and see a beautiful country,” he said.

“We’re going to get a chance to work with the Royal Marines – and our traditions are their traditions, we’re an outgrowth of the Royal Marines so there’s a special relationship there. Working with NATO partners, working with especially the Norwegians who have been exceptional hosts. And then I’ve never been to Iceland either, so I’ve been doing this for a long time and it’s cool to get to go to some place that I haven’t been before.”