A new drain strainer orifice installed on a USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) steam line fits in the palm of a hand, but its significance to future shipbuilding is enormous.

Created on a 3D printer by Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) Newport News Shipbuilding, the relatively small part is designed to maintain steam pressure when removing condensation from a line by preventing steam from escaping. However, the process to manufacture this part is a leap in shipbuilding likened by engineers to the 1930s and 1940s, when modern welding processes quickly replaced rivets in joining steel plates on ship hulls.

“This is a watershed moment in our digital transformation, as well as a significant step forward in naval and marine engineering,” Charles Southall, the vice president of engineering and design at Newport News Shipbuilding, said in a statement. “We are committed to partnering with the Navy to ensure that collectively, we are investing in every opportunity to improve and advance the way we design and build great ships for the Navy.”

Newport News Shipbuilding, which builds the U.S. Navy’s nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and submarines, is optimistic about the future of 3D printing. If 3D-printed parts can pass Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) standards, the hope is using the process, also called additive manufacturing, will both speed up the time to complete orders and cut down on production costs, HII officials told USNI News.

The idea of using 3D printing to manufacture metal parts came from John Ralls, a senior engineer at Newport News Shipbuilding, Southall said in a video posted to the HII website. Ralls started exploring 3D printing for shipbuilding about six years ago, he said in the video.

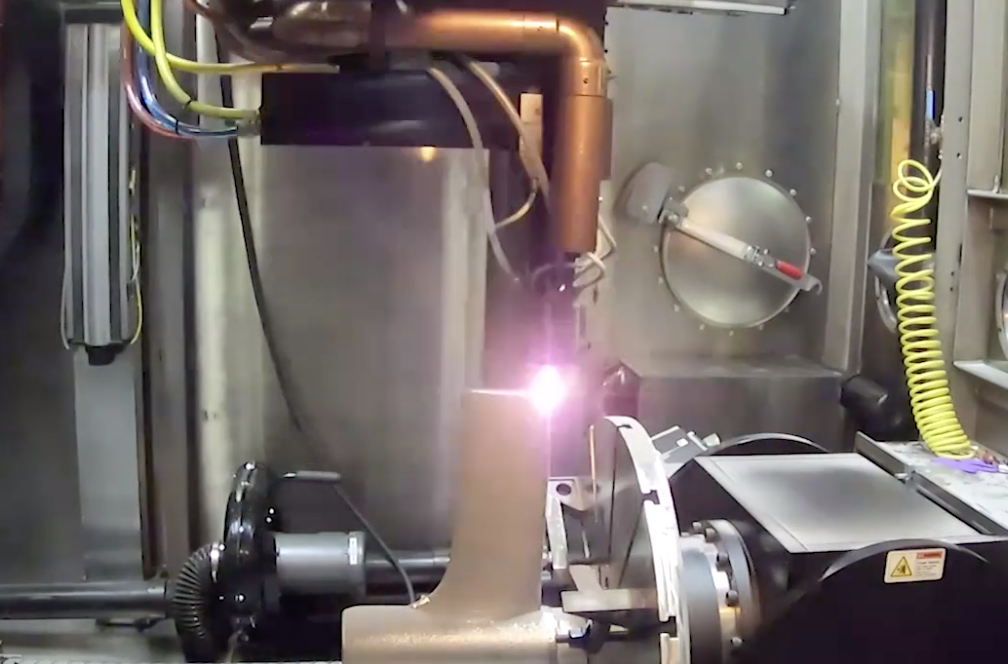

“If you asked me ten years ago, would I be working on taking powderized metal and lasers to make a part in three-dimensional shapes, I don’t think I could have envisioned that at all,” Ralls said.

HII describes the 3D printing process approved by NAVSEA as “a highly digitized process that deposits metal powder, layer by layer, to create three-dimensional marine alloy parts that potentially replace castings or other fabricated parts, such as valves, housings, and brackets.”

The Navy also hopes 3D-printed parts will prove to be a way to supply the fleet quicker, cheaper and more efficiently. The particular drain strainer orifice installed on Truman will be monitored for a year to evaluate how well the part performs in a real-world working environment, according to a NAVSEA statement.

“This install marks a significant advancement in the Navy’s ability to make parts on demand and combine NAVSEA’s strategic goal of on-time delivery of ships and submarines while maintaining a culture of affordability,” Rear Adm. Lorin Selby, the NAVSEA Chief Engineer and Deputy Commander for Ship Design, Integration, and Naval Engineering, said in a statement.

Meanwhile, the Navy in the process of understanding how to safely apply additive manufacturing technologies in more ways, including as part of the supply chain for aircraft carriers at sea.

“Specifications will establish a path for NAVSEA and industry to follow when designing, manufacturing and installing AM (additive manufacturing) components shipboard and will streamline the approval process,” Justin Rettaliata, the Technical Warrant Holder for Additive Manufacturing with NAVSEA, said in a statement.

Two recent additive manufacturing efforts led the former in-service carrier program manager at the Program Executive Office for Carriers to decide the Navy should install a 3D printing lab aboard USS George Washington (CVN-73) during its ongoing mid-life refueling and complex overhaul.

Capt. John Markowicz, who until this summer served as the in-service carrier program manager, told USNI News in a May interview that the Naval Surface Warfare Center Carderock Division had worked to understand how a 3D printer would operate at sea, on a structure constantly in motion.

Meanwhile, the chief engineer aboard USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74) was already experimenting with how to use 3D printing as a way to shorten the supply chain for the ship’s industrial maintenance, Markowicz said.

In August, Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Chung-Hoon (DDG-93) needed to replace a bolt from a hangar bay door roller assembly. Cmdr. Kenneth Holland, the chief engineer aboard Stennis, offered to make a replacement bolt for Chung-Hoon, which was part of the Stennis Carrier Strike Group.

“The printers are being used right now to resolve issues while they’re small problems,” Holland said in a statement released shortly after the event. “It’s used to help manufacture parts that you can generally only get if you buy the higher assembly.”

Holland and his team aboard Stennis have made replacement knobs for communications gear and other small components, according to the Navy. Currently, small manufacturing jobs are the most likely jobs 3D printing can accomplish at sea, Markowicz said during his May interview with USNI News.

More work has to be done for the Navy to understand what standards required for different kinds of parts and the limitations of 3D printing. When it comes to parts for critical systems, Markowicz said shipboard labs might never be approved to create such items as parts of steam propulsion systems. A shipboard facility doesn’t have the means to test and certify parts like a shipyard facility.

However, Markowicz said a shipboard lab could print something like a pump shaft with plastic or Teflon first, test fit it on the ship, and then re-print the piece with metal for actual use on the ship