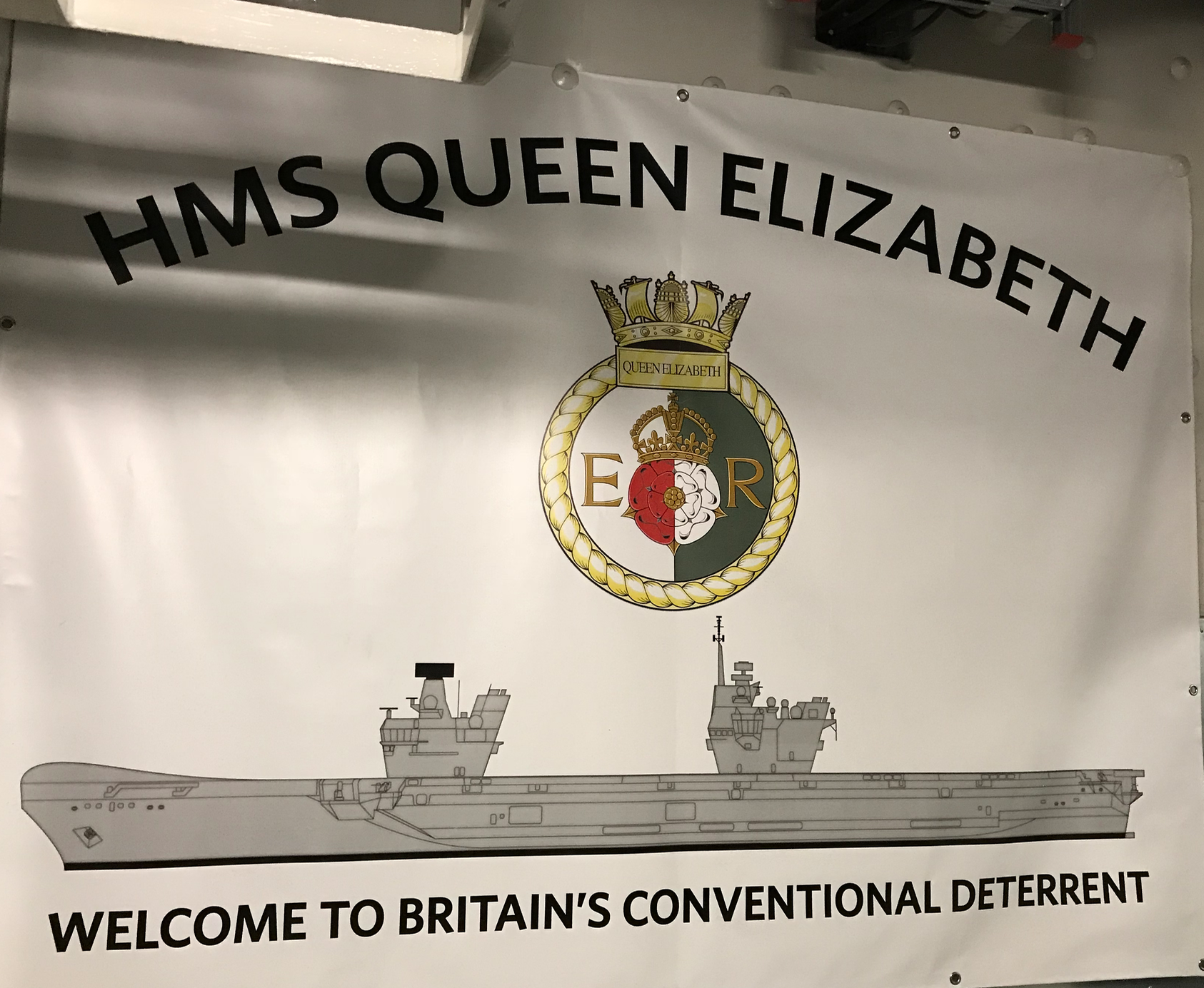

ABOARD HMS QUEEN ELIZABETH, OFF THE COAST OF NEW JERSEY – The Royal Navy lays out the intentions of its largest warship to visitors immediately.

“HMS Queen Elizabeth: Welcome to Britain’s Conventional Deterrent,” reads a giant sign hanging in the carrier’s second island, over a ladder well just off the flight deck.

The 70,000-ton carrier and its sister ship, Prince of Wales (R09), and their embarked air wings of F-35B Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters are set to be the centerpiece of Britain’s nascent carrier strike group construct. The move – after years of starts and stops – is reshaping the Royal Navy from a force that was a key NATO partner focused on anti-submarine and mine warfare in the Cold War to one that will blend closely with the carrier forces of American and French allies.

“The U.S. has 11 carriers,” ship commander Capt. Jerry Kyd told USNI News last week.

“We’ll bring two more for the good guys, as we see it.”

The ship was off the East Coast last week conducting the first shipboard F-35 tests with American aircraft, kicking off several years of testing ahead of a planned deployment in 2021.

“We used to do this a lot in the U.K., but we’ve had a bit of a gap getting back into the carrier strike business,” Royal Navy Commodore Andrew Betton, commander of the U.K. carrier strike group, told USNI News last week.

“[We’re] working alongside our French and U.S. partners to understand the most effective way of fighting and operating a carrier strike group.”

Last year, the heads of the U.K., French and U.S. navies signed a formal trilateral cooperation agreement for three navies to work together in the realm of carrier operations and anti-submarine warfare.

“[We] share many national security challenges, including the threats posed by violent extremism and the increasing competition from conventional state actors,” the one-page agreement read.

“More than ever, these threats manifest in the maritime domain. Given these common values, capabilities, and challenges it makes sense for our navies to strengthen our cooperation.”

In particular, the Russian submarine force has been on an aggressive modernization drive and operating attack boats at a rate not seen since the Cold War – which is seen as the prime driver of the recent U.S. focus in the Atlantic. That boost in activity in the Atlantic comes as the U.S. and U.K. are in a period of naval reset after 17 years of operating in support of ground forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The U.K. is working through a gap in fixed-wing aviation at sea, after London decided to scrap the Royal Navy’s light carriers and fleet of GR7 and GR9 Harrier strike aircraft earlier in the decade. To maintain skills, the U.K. has relied on an extensive exchange program with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps and the French to keep some carrier skills native in the Royal Navy.

“We’ve had lots of individuals, pilots, maintainers, etc., operating onboard your flattops of various descriptions, but also we’ve had U.K. units join American [aircraft carriers] on deployments around the world and indeed the French carrier,” Betton said. “The mutual support and interoperability – we haven’t stepped completely away from that, and what we’re trying to rebuild now is the sovereign carrier strike group that we can plug in with allies as and where required.”

While the intent of the Ministry of Defence was to field a completely U.K.-generated carrier strike group and air wing, the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force are still years off from that capability. The first operational deployment of the U.K. carrier strike group in 2021 will have an air wing built around U.S. Marine Corps F-35Bs assigned to the “Wake Island Avengers” of Marine Fighter Attack Squadron (VMFA) 211, in addition to the RAF’s 617 Lightning F-35B Squadron. As of this summer, the U.K. has received about 16 of the 43 F-35Bs it’s ordered, which prompted the planned deployment of the U.S. Marines on Elizabeth.

The reliance on Marines for the first deployment was presented as a benefit of the program rather than a liability.

“We’re international by design, but there will be a sovereign core to the task force. But we very much look forward to working with allies, whether that is at range or as an integral part of the task group,” Royal Air Force Air Vice-Marshal Harv Smyth, the commander of the U.K.’s fast-jet units, told reporters last week on Elizabeth.

“There are options there.”

While the Royal Navy has operated fixed-wing aviation from ships in the recent past, the level of cooperation proposed between the U.S. and the U.K. for carriers strike group operations will be the largest in decades, Chris Carlson, a retired U.S. Navy captain and naval analyst, told USNI News on Friday.

“With the Brits now trying to integrate their carrier with ours, there isn’t anything in the recent past that gives them something to base this on,” he said.

During the Cold War, the U.K. had a fleet of three 22,000-ton Invincible-class carriers that fielded Harriers that arguably provided little utility in maritime operations and air defense operations, Carlson said.

“Harriers had short legs. They didn’t have a really good air intercept radar, it was just really hard for us to put them in, so [the Invincibles] were looked at as being the centers of ASW escort groups because they could carry a ton of helicopters and the Brits were really good with ASW.”

The new cooperation between the U.S., French and U.K. navies will be key to making the British and French get the most out of their carrier forces. Both the U.K. and French are short on carrier escorts and will have to rely on allies.

“It’s making a virtue out of a necessity,” Carlson said.

“They’re going to have to partner with us. They’re going to have to partner with the French because neither one – the French or the Brits – can do sustained operations with a decently balanced [carrier strike] group.”

The current plan is for the Royal Navy to continue testing the carrier strike group into the next decade, with more F-35B testing off the East Coast of the United States next year and a group sail to certify the strike group in 2020, Elizabeth commander Kyd said.

“That’ll be another two years before we’re ready to go out,” he said.

“The first deployment is ’21. Who knows where, but we’ll be ready.”