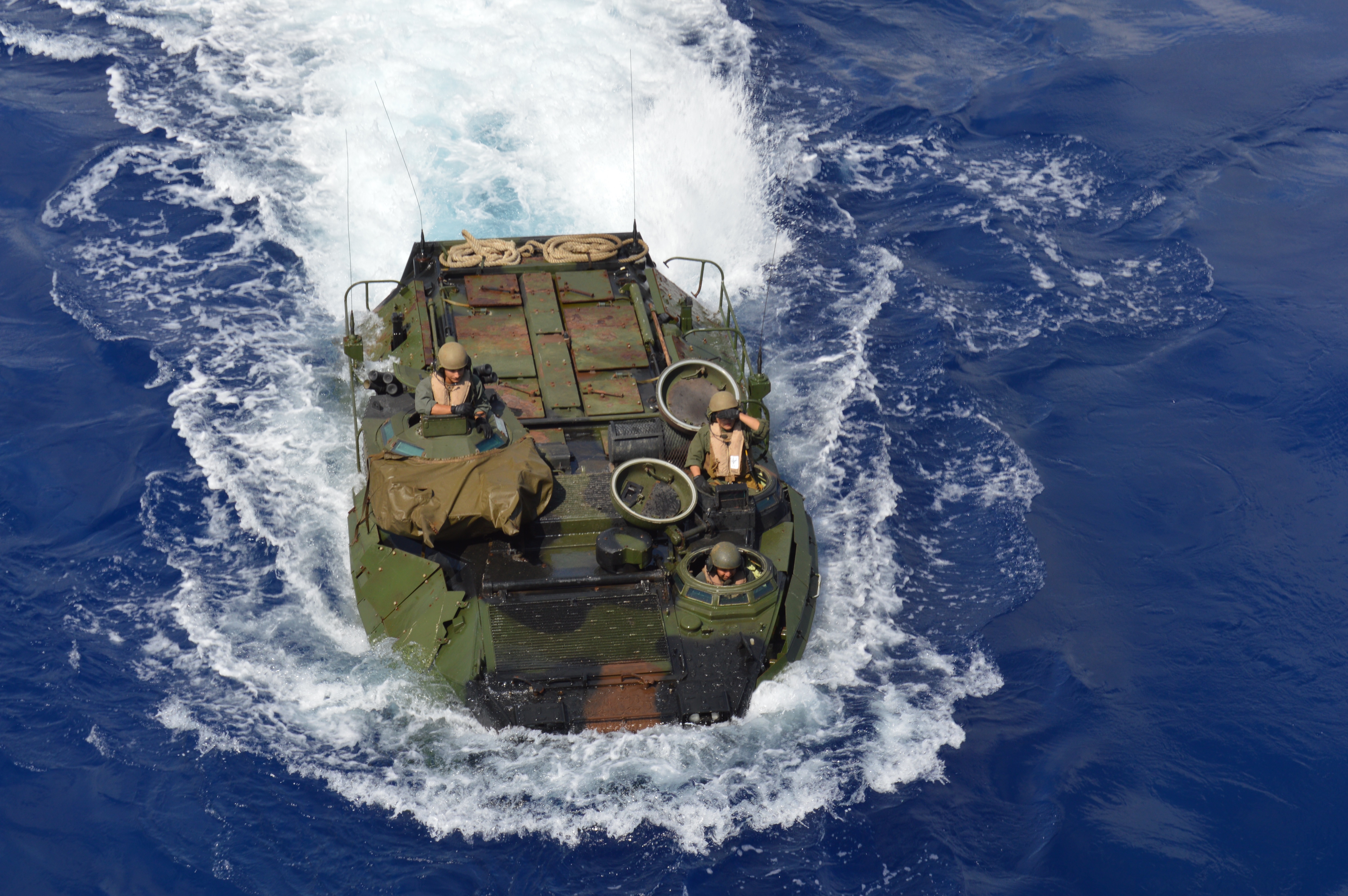

ABOARD HMAS ADELAIDE, OFF THE COAST OF HAWAII – As U.S. Marine Corps amphibious assault vehicles (AAVs) lined up in the well dock of the Australian amphibious assault ship HMAS Adelaide (L01) to head to the big island of Hawaii, the vehicle operators had all the hatches open.

As well dock crews’ red flags turned to green flags and the AAVs were sent one by one out the back of the big-deck amphib, the hatches remained open. There were no big splashes. The vehicles didn’t sink and have to float back up. They swam nicely out the back – and in world-record time, according to the ship’s dock officer.

The Australian’s LHD – built by Navantia based on the design of the Spanish Navy’s Juan Carlos I – differs from an American LHD in a couple key ways, one of them being the well deck (which the Australians call a well dock).

In an American amphib, despite the ship ballasting down to allow the well deck to flood, the AAVs’ tracks maintain contact with the floor and then a ramp during their exit from the ship. When they drive off the end of the ramp and lose contact, there’s a splashdown, with the AAV mostly or sometimes fully sinking under the surface of the water before bobbing back up. For the 20-plus combat-ready Marines in the back, in a dark passenger cabin that reeks of diesel fuel, that evolution is particularly unpleasant.

In the Australian amphib, though, the well dock is built at such a slope that the AAV begins to float before it gets halfway down its lane towards the back of the ship. With the AAV already floating, there’s no major splash and no sinking – though a handful of AAV drivers proved that starting the evolution at too high a speed can create a wave in the well dock that comes back to douse them standing in the open hatches.

The discovery that record-setting AAV operations can be conducted with U.S. Marine AAVs and Royal Australian Navy ships highlights the main point of the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise, during which this operation took place: interoperability.

“If we need to conduct any future ops with Australians, I’m confident it would be a seamless execution,” U.S. Marine Corps 2nd Lt. Nolan Paduda, the AAV platoon commander for Combat Assault Company, told USNI News on July 22 from the Adelaide well dock. He reminded visitors to the ship that, though the operation looked smooth, it was the first time a full platoon of AAVs had ever operated on an Australian ship.

“This is extremely smooth and pretty straightforward and simple. So it’s pretty easy; full trust and confidence that any Marine of any rank or level of capability can splash off this ship, and I’m not worried about them as far as doing their job,” Paduda said of operating off Adelaide.

“Coming back in is just as easy. The crew here has done an amazing job at picking up the American hand and arm signals and being able to position us in the well deck where we need to go.”

For Lt. Cmdr. Sandy Jardine, the ship’s first lieutenant and dock officer, the successful integration of his crew and the American AAV platoon comes after two years of planning and number-crunching.

In the 2016 RIMPAC exercise, sister-ship HMAS Canberra (L02) participated in the exercise and took on four AAVs to certify that they could enter and exit the well dock.

In the intervening two years, Jardine was hard at work, finessing the standard operating procedures (SOP): the time and distance between AAVs during their launch, the order the vehicles would come and go in, how to spin the AAVs in the well deck so they could back into their parking spots, how to adhere to standard American hand and arm signals to the AAV drivers, and more.

With the AAVs swimming through the well dock instead of driving, the AAVs can launch and recover with much less distance between vehicles, Jardine said.

Despite the first live practice of launching and recovering an AAV platoon coming once RIMPAC had already started, Jardine joked they had set world records for the speed of the launches in particular.

“Never. Never been able to rehearse it. So the first time we’d done it was when we brought them on from Pyramid Rock [Beach on Oahu]. And that was a 21-minute recovery,” Jardine said of the first full-platoon recovery.

“The next time we kicked them out, it was six minutes to get them out. The second time we kicked them out was five minutes 43 (seconds), and we’re now down to five minutes four (seconds). So we’re getting faster, and that’s as the dock crew gets more confident and the AAV crews get more confident.”

He said certain decisions – such as ensuring the platoon’s gunnery sergeant was on the first AAV in, so he could get out of the vehicle and help the Australian crew with the hand and arm signals – set them up for success.

“If you look at what we’ve done since we’ve been here, it’s pure interoperability,” Jardine added, noting the Australian Navy was looking to get even better at these bilateral AAV operations.

“We’d done it in ‘16, we proved the concepts. We’ve come back this time and basically taken it to another level. And then when we come back for the next one, we’ll be at an even better level,” he said of RIMPAC 2020.

“We have a big exercise next year called Talisman Saber, and that’s where we put the icing on the cake, and then we come back on the next RIMPAC and we put the cherry on top.”

Though the Australian Navy isn’t setting its eyes on a major amphibious battle – most of its current international Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2018 deployment is focused on partnership-building and humanitarian assistance/disaster relief types of missions – Jardine noted how the U.S. and Australian forces could pair up for a very effective first wave of an amphibious assault: Adelaide can carry 15 AAVs as normally configured, or 30 if the heavy tank deck were cleared out. If the tanks were removed and 30 AAVs were loaded on, the 30 AAVs would bring 620 men ashore. If followed by the four landing craft Adelaide carries – similar to the landing craft utility (LCU) on the American amphibs – which could bring 120 troops apiece, that creates a landing force of 1,100.

“So over a thousand men in the first wave, which is pretty impressive,” he said.

“That’s better than D-Day.”