JOINT BASE PEARL HARBOR-HICKAM – The Navy may once again arm its attack submarines with the Harpoon anti-ship cruise missile, after a sub-launched Harpoon performed well during a sinking exercise this month in the biennial Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2018 exercise.

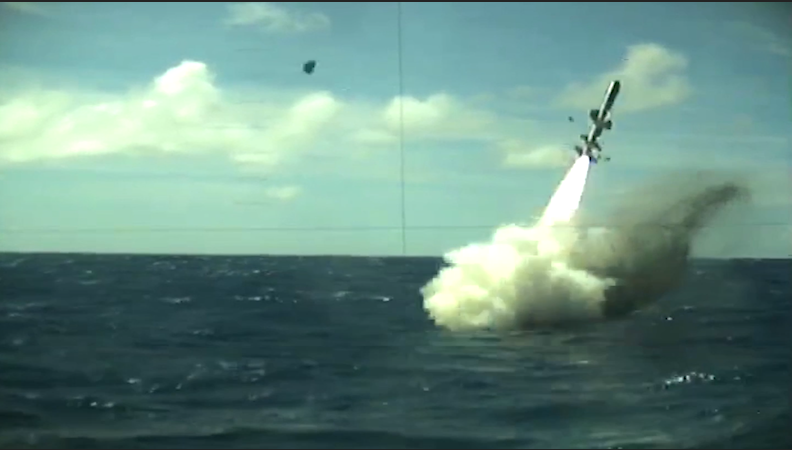

Los Angeles-class attack submarine USS Olympia (SSN-717) fired a Harpoon at the ex-USS Racine (LST-1191) during the first of two SINKEX events in RIMPAC this month. That shot marked the first time a Harpoon had been fired from a U.S. submarine in more than 20 years, and Commander of U.S. Pacific Fleet’s Submarine Force Rear Adm. Daryl Caudle said he expects that the cruise missile will be added back into the SSN’s regular armament.

“The old guys like me actually were on ships that had Harpoons. So it has been a long time since we’ve actually had it onboard our ships,” the admiral joked during a July 25 interview in his office in Pearl Harbor. He said the missile was “designed predominantly to go against Russian ships and their surface action groups – Cold War – from our submarine force.” But as that threat declined and modernization dollars were needed elsewhere, the Harpoons went out of favor.

“We thought we could get by with our heavyweight torpedo, our advanced capability (ADCAP) Mk 48 torpedo, because we thought the predominant threat at the time when that decision was made was submarines, instead of needing the standoff distance of an anti-ship cruise missile. We took those missiles and, like we do so well in our Navy, we shelved them and thought we may need to bring them back.”

As the global threats the Navy faces have evolved, leadership decided about a year ago that it was time to pull those old Harpoons back off the shelves.

“Today’s highly capable navies and adversary countries, the competitive countries we’re in great power competition with, have extremely good surface ships with very capable missile systems themselves. So to be able to actually improve our lethality at ranges much greater than the Mk 48 torpedo, we want to actually bring back an anti-ship cruise missile,” Caudle said.

“The way to bring back that in a phased way was to basically go to our Naval Undersea Warfare Center, NUWC, and have them reconstitute the capability, to build the software necessary to use our existing combat control system and talk to that Harpoon cruise missile. Olympia was chosen because we knew she was going to be part of RIMPAC. … We decided to shoot for the 2018 RIMPAC to test the Harpoon cruise missile system again. So this has been at least a year in the making. The folks doing the software coding were working hard up in Newport to get that system built, that coding built. The guys onboard the squadron here, Submarine Squadron 7 that owns the Oly (Olympia), working hard on that ship to practice the tactics, techniques and procedures to shoot the Harpoon; had to bring those back out of the mothballs as well to actually know the language that we speak to prepare for firing and actually shooting the weapon. So had to dust those procedures off.”

What happened next was partly a great performance due to hard work by the submarine community, and partly a serendipitous set of events.

With two Harpoons loaded – one as a backup – Olympia “got in position on the range at PMRF (Pacific Missile Range Facility), which is over off of Kauai. We thought we were going to have to shoot second, and as luck turned out and I was very thrilled, the Air Force mission which was to shoot a LRASM, a long-range anti-ship missile, they got delayed, so we got to shoot first. We shot the Harpoon perfectly, went into cruise and hit the ex-Racine, which is an LST, dead center,” Caudle said of the July 12 SINKEX.

“The beautiful part of this is, the Oly was not expected to shoot the torpedo too. They had been scheduled for the next hulk (decommissioned ship) to shoot the Mk 48, but the way that things unfold in real world, the shooters changed that day, so Oly got tasked about mid-day to go and actually shoot an ADCAP also. … So we got to move into position and actually then shoot the heavyweight torpedo. That torpedo, again, a warshot, worked perfectly, went out there and did its job and honed in on the Racine, broke its keel, and a couple hours later it was on the bottom. Our torpedo is an extraordinary weapon, it really is.

“So the interesting part is, you can see kind of almost a tactic there that I think is important that we got to practice just by happenstance: shooting a long-range shot and then move in for the close-range shot,” the admiral concluded.

Though the decision for if and how to bring back the Harpoon missile to the attack sub fleet is out of his hands – leaders back in Washington will work through that process – Caudle said “no question” the missile shot was a success and “from my perspective, it worked flawlessly.”

The undersea warfare directorate (OPNAV N97), the Program Executive Office for Submarines, NUWC and others will now study the shot, ensure that it did in fact meet all criteria, “and then there will be a decision made about how to phase that weapon back in and to what extent we’ll phase it back in,” he said.

“So that’s a decision that’s yet to be made, but the shot by the Oly will inform that decision.”

Depending on what N97 and the PEO find, Caudle said there could be another Harpoon test shot if another aspect of its performance needed to be validated, or engineers needed to validate the interoperability between the missile and a different iteration of combat system software. But, he said, “I would say what we learned from this test would be sufficient to field it, from my perspective.”

Additionally, the SINKEX that sent Racine to the bottom of the Pacific also proved out a ground-to-ship missile capability that has been in the works for several years. Both the U.S. Army and the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force shot at Racine from ashore in Hawaii, with the Japanese firing a surface-to-ship missile and the Army firing a Naval Strike Missile (NSM) from a launcher on a Palletized Load System. This was the first time ground forces had ever participated in a SINKEX at RIMPAC.

“When you normally think of a SINKEX you think of ships shooting other ships kind if thing. But we’ve now gotten to the point we have capabilities where Army and the JGSDF both have the ability to shoot a surface-to-surface missile from ground to ocean in a maritime environment. And that becomes a big deal, so to coordinate the maritime environment we need to incorporate the multi-domain task force of the U.S. Army into this, as well as the JGSDF,” Vice Adm. John Alexander, commander of U.S. 3rd Fleet who led RIMPAC, said in a July 20 press conference.

Eric Sayers, who previously served as a special assistant to the Commander at U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and is now an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, said this year’s SINKEX was important for several reasons, and showed significant growth in Pacific theater capabilities in recent years.

“First, and perhaps most importantly, you have a Japan that is willing to publicly display their advanced land-based, anti-ship capabilities alongside U.S. forces. This should not be overlooked and it is really the result of the leadership of Japan’s Chief of Defense, Admiral Kawano. When Japan was invited to join this effort last year, it was Kawano who helped ensure the Ground Self-Defense Force took part. This is a great demonstration of what the future of alliance cooperation can look like,” Sayers told USNI News.

“Second, you have a U.S. Army that is slowly but steadily embracing this land-based, anti-ship mission that just a few years ago they wanted nothing to do with. In fact, despite the role it could play in deterrence and warfighting in the Pacific as well as elsewhere, it was shunned openly as a costly and dated mission. It was only after the determination of key individuals at [U.S. Army Pacific], [U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command], [Strategic Capabilities Office], and PACOM that the argument was won and we are now moving in the direction you see on display in Hawaii. This is an example of the type of innovation in military warfighting concepts that are only possible when motivated officers and civilians, often with minority views, can make a compelling argument about the future of war and successfully maneuver a bureaucratic path forward.”

Sayers added that, in sum, the two SINKEX events at RIMPAC showed a “multi-axis strike capability” the U.S. is developing and could field in a few years. He noted it was just earlier this decade, when Adm. Robert Willard led PACOM from 2009 to 2012, that PACOM “was sending urgent operational needs statements back to Washington for an anti-ship weapon.”

“Today, this SINKEX is showing the Congress, our allies, and the Chinese that we have air, ground, surface, and undersea options for the anti-ship mission. We aren’t there yet, but we are slowly moving in the right direction,” Sayers said.

The Racine SINKEX also included a Harpoon shot by a Royal Australian Air Force P-8 Poseidon aircraft, which was the first time the Australian plane had participated in a RIMPAC SINKEX.

The second SINKEX put ex-USS McClusky (FFG-41), an Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate, at the bottom of the ocean much faster than anticipated. The Singapore Navy shot two Harpoon missiles at the frigate, and “typically if you shoot a Harpoon and it hits above the waterline it’ll punch a hole and blow up but it won’t sink a ship; theirs just happened to hit at the waterline and the ship started sinking about halfway through the event, so there were some countries that didn’t get to shoot their missiles and weapons, but for the most part the SINKEXs have been a success.”

In all, six Harpoons were successfully shot between the two SINKEX events, according to manufacturer Boeing.