CAPITOL HILL — The Naval Safety Center is standing up a new Knowledge Management and Safety Promotion directorate, which will use data analytics to help get ahead of potential future mishaps.

Though the creation of the new directorate came out of the U.S. Fleet Forces Command-led Comprehensive Review last fall following two fatal surface navy collisions, Naval Safety Center commander Rear Adm. Mark Leavitt said it will also help address the rising number of naval aviation mishaps.

Speaking at a House Armed Services tactical air and land forces subcommittee hearing on Wednesday, Leavitt said, “based on the findings in the Comprehensive Review and the Strategic Readiness Review, we are working with fleet and type commanders to aggregate training and other data sources so we can conduct complex modeling and analytics. This will allow us to provide a holistic picture about the overall health and risk-level of units. Such analysis will provide preventative solutions that naval leaders can use to make decisions that reduce unnecessary exposure to risk. Getting this right is of vital interest to our Navy/Marine Corps team: our people are our greatest asset, and keeping them safe is our responsibility.”

He told the subcommittee that the center would go beyond looking at mishap investigations and hazard reports and would also consider operational, personnel and other data so that “we can become much more predictive in discovering what could come in the future for occurring mishaps – getting left of the bang, as I like to put it.”

Leavitt told USNI News after the hearing that the Navy plans to increase funding for the Naval Safety Center in Fiscal Years 2018 through 2020 to help set up an office of 25 to 30 uniformed personnel and civilians. A doctorate-level researcher has already been hired to serve as the Knowledge Management and Safety Promotion director, the admiral said, and the Army Analytics Group will contract with them to do data analytics until an organic capability is eventually built up within the directorate. In addition to data scientists, Leavitt said subject matter experts – aviators, surface warfare officers, maintenance personnel, deck handlers and more – will also work in the office to ensure that the projects the data scientists take on are operationally relevant and would lead to better managing risk in the fleet.

Leavitt said the directorate’s aim is to see hazards before the fleet sees them and to “drive to zero preventable mishaps.”

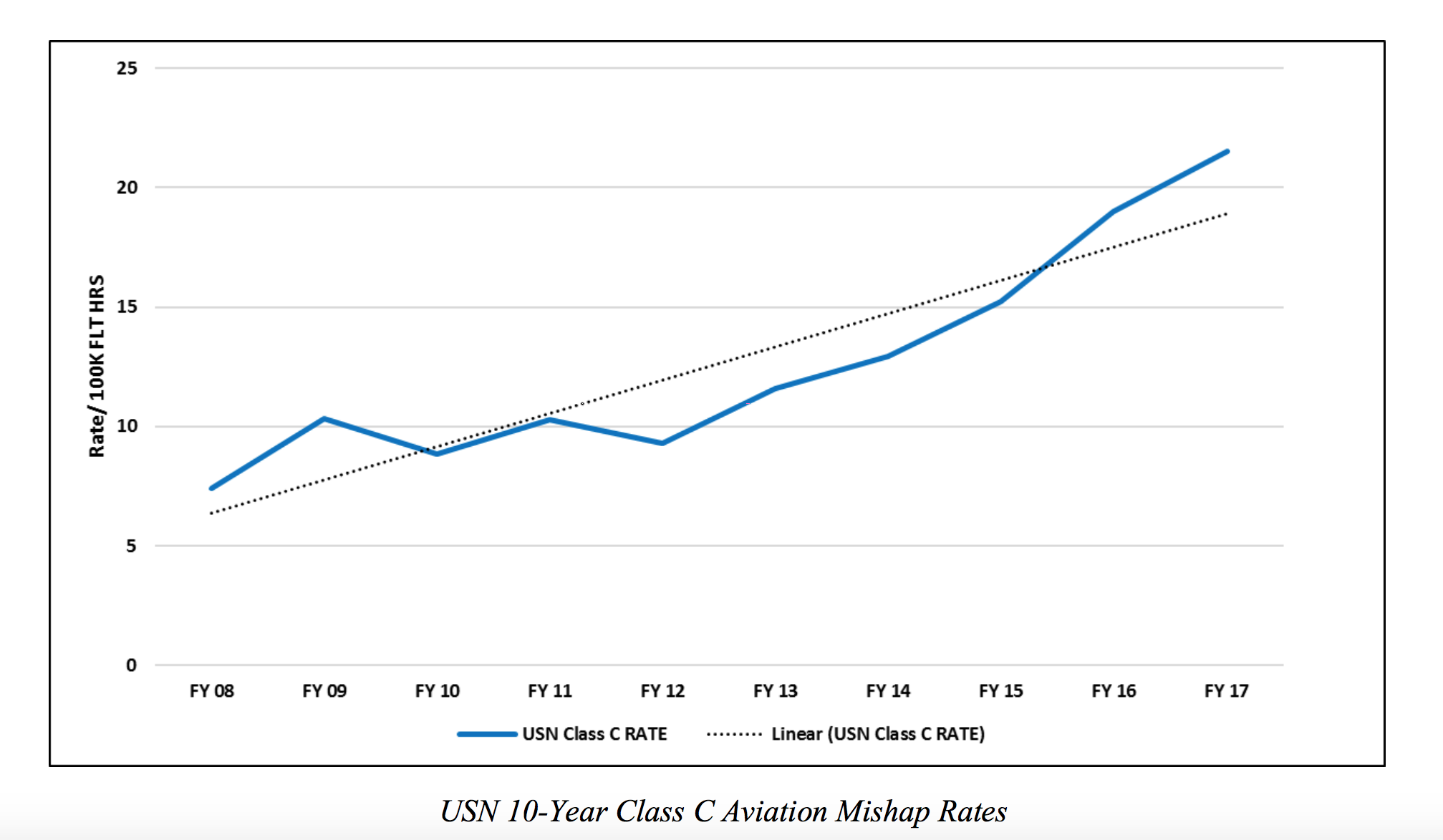

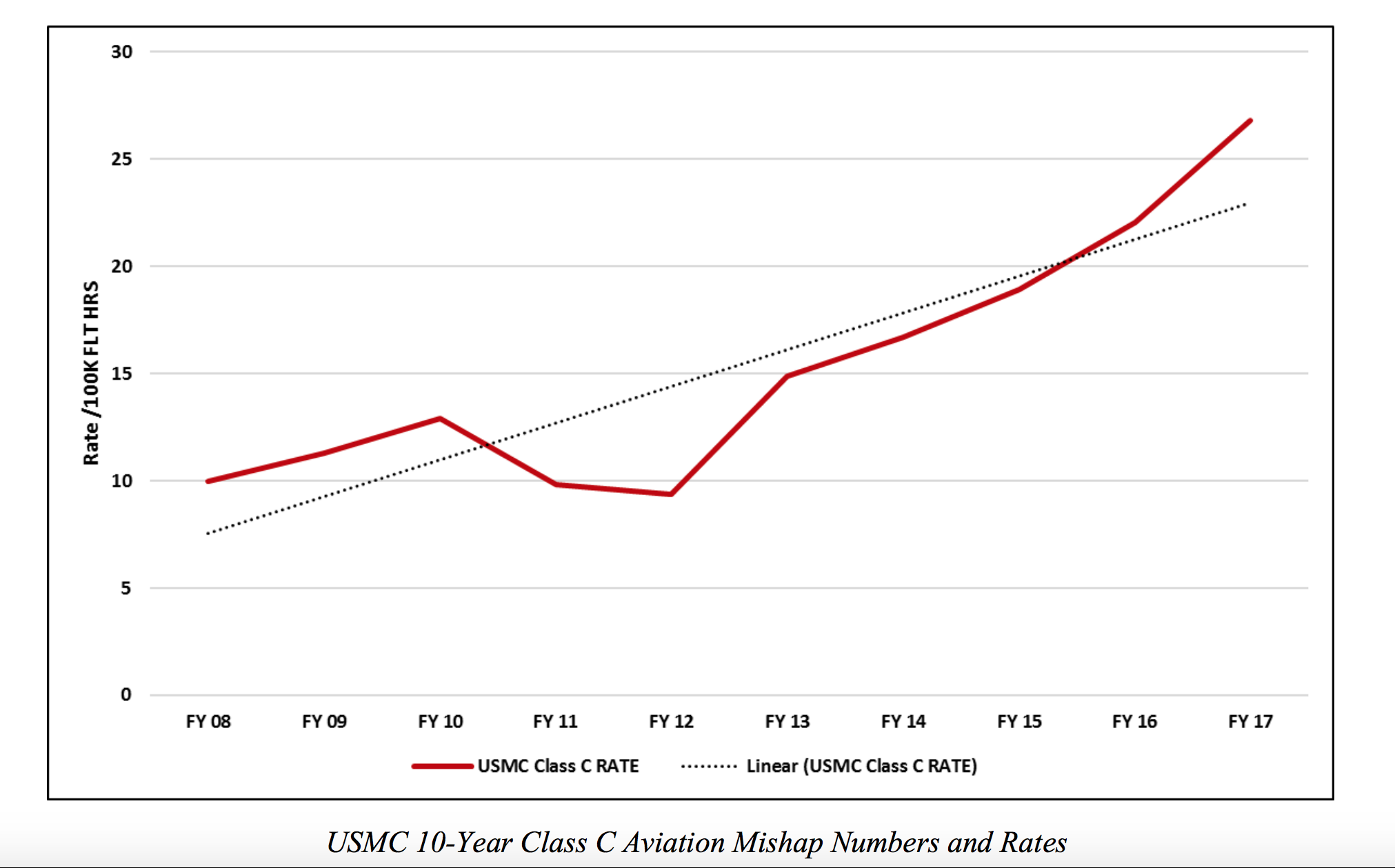

The Naval Safety Center has its work cut out for it, though. According to Leavitt’s written testimony to the subcommittee, both the Navy and Marine Corps have seen a dramatic increase in Class C mishaps.

“The naval enterprise is currently investing a great deal of its analytical efforts to understand the recent rise in Class C mishaps, those costing the government between $50,000 and $500,000 or nonfatal injuries or illnesses that result in one or more days away from work. This rise is affecting both the USN and the USMC. Additionally, the majority of these mishaps are aviation ground mishaps, rather than flight or flight-related mishaps. The bulk of these mishaps occur during maintenance evolutions and involve aircraft striking or being struck by other objects. Multiple discrete studies from numerous sources point to inexperience in the E-5 and E-6 maintainer rates as a significant contributing factor,” according to the document.

“A recent USN study showed that F/A-18 and MH-60 squadrons, the largest aviation communities in terms of density of squadrons and aircraft, are experiencing the largest numbers of these mishaps. Human factors analysis studies point to breakdowns in organizational teamwork, an analysis category defined as the interaction among individuals, crews and teams involved in the preparation or execution of a task that resulted in human error or an unsafe situation. This breakdown could be related to the E-5 and E-6 inexperience issues previously noted. A similar study on USMC Class C aviation mishaps showed the same type of performance-based errors, and suggested applying the largest effort to the MV-22 and F/A-18 communities.”

From FY 2008 to FY 2017, the Navy’s Class C mishap rate rose from about seven and a half per 100,000 flight hours to about 22 mishaps per 100,000 flight hours. For the Marine Corps in that same time period, Class C mishaps rose from about 10 to about 27 per 100,000 flight hours, according to the document.

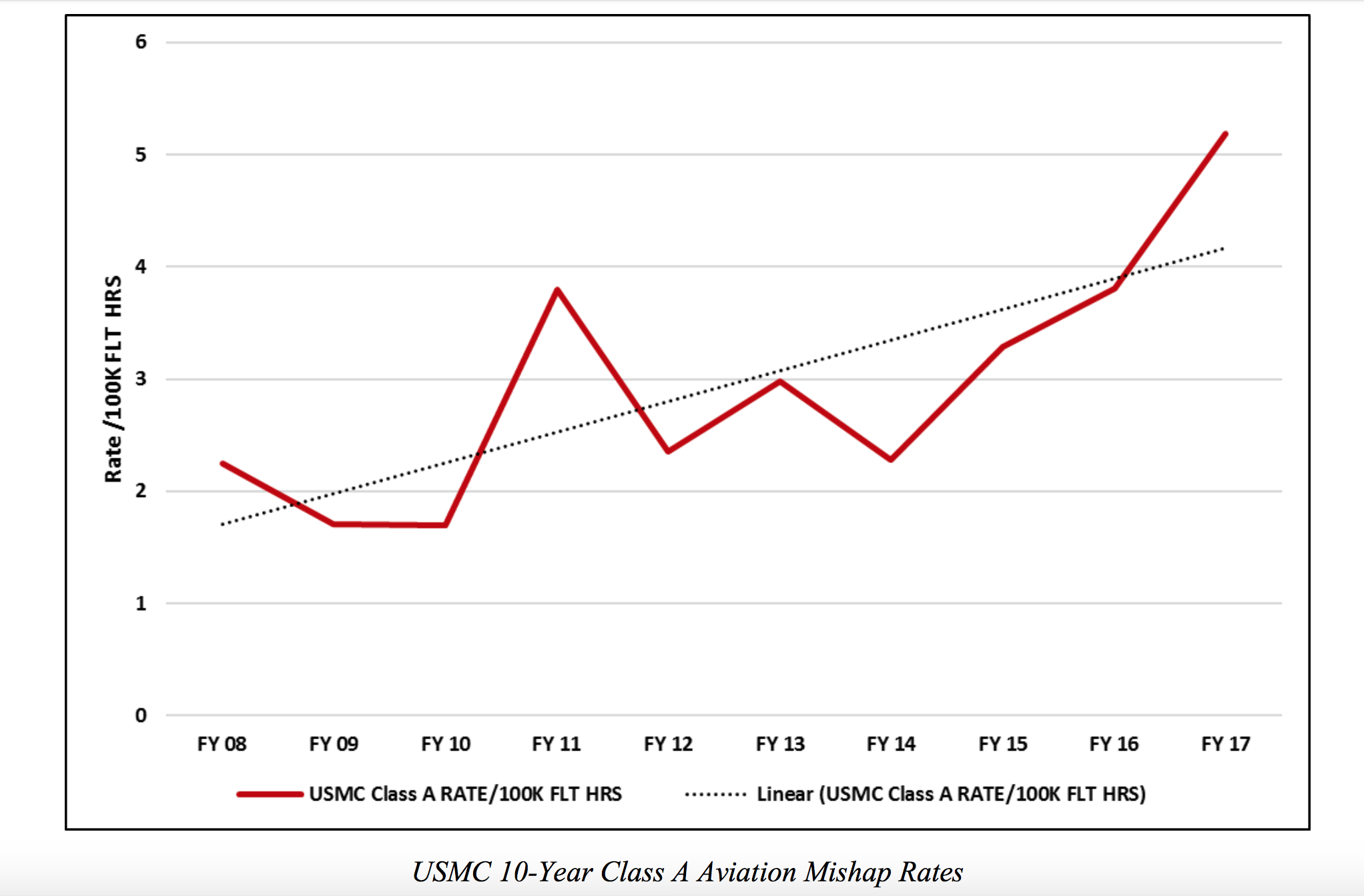

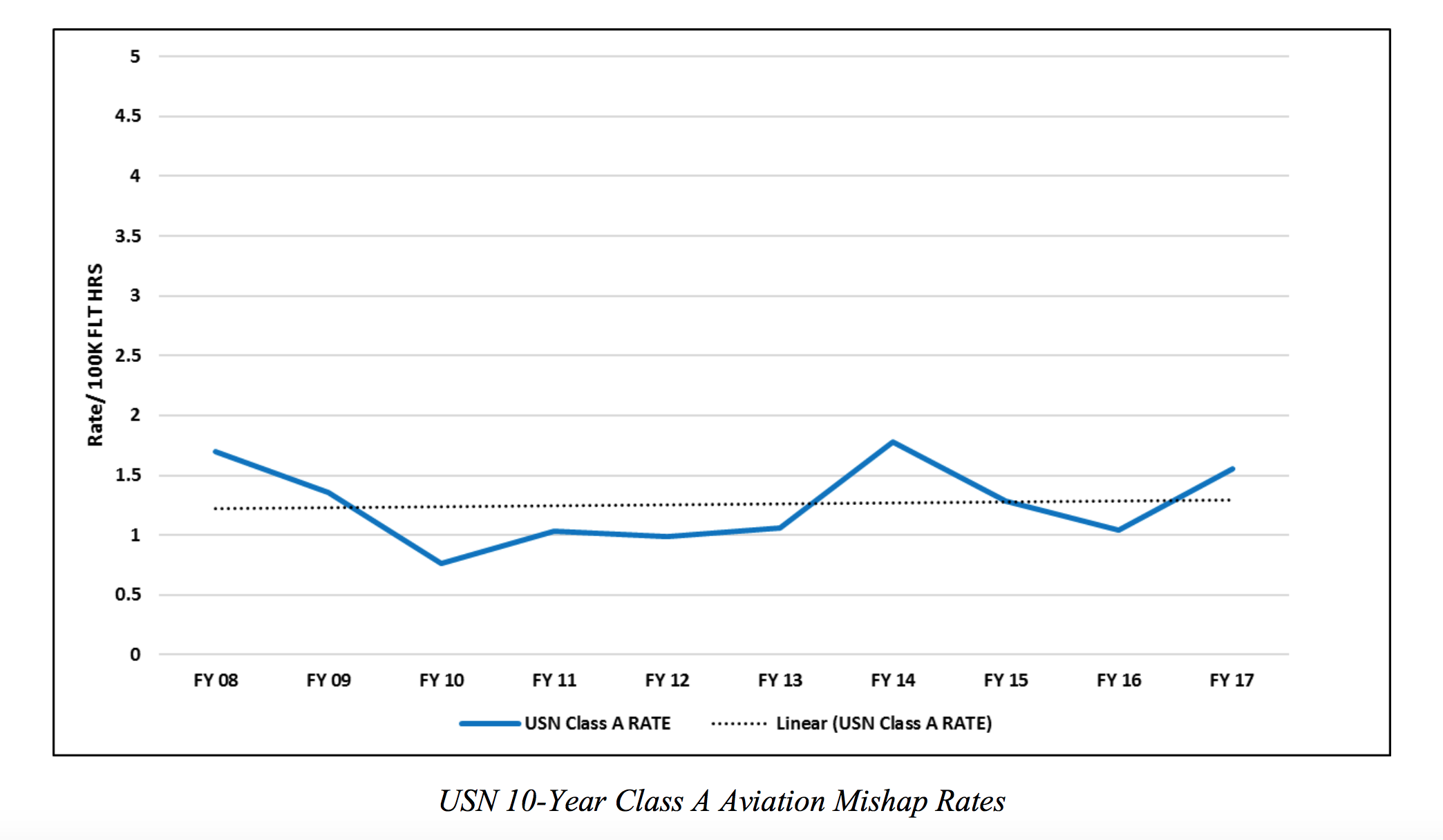

On Class A mishaps – those involving a death or permanent disability, the total loss of an aircraft or more than $2 million in damages – Leavitt’s written testimony classifies the Navy’s rate as relatively consistent over the last 10 years and the Marines’ rate as rising – though during the hearing Leavitt said the Marines’ mishap rate over the last decade has been within “normal” rates, with a couple years like last year being aberrations.

On the Navy side, Class A mishap rates bounced between about 0.75 and 1.75 mishaps per 100,000 flight hours, with no noticeable trend upwards over time. For the Marines, 1.75 mishaps per 100,000 flight hours was the low point on the chart, with 2017 jumping to more than 5 Class A mishaps per 100,000 flight hours.

The written testimony notes a decrease in overall flight hours in recent years: “Total USN flight hours averaged 942,000 between FY08 and FY12, in the years before sequestration. In the last five years, flight hours have averaged about 90,000 less. … USMC flight hours are about a third of the USN’s, averaging 302,000 between FY08 and FY12. In the last five years, those averages have dropped by approximately 50,000 hours.”

Still, Leavitt said during the hearing that there is no correlation between flight hours and the rate of mishaps.

“The Navy/Marine Corps team has not been able to draw a direct correlation between a lack of flight hours and an increase in mishaps. What we have discovered is, through a study that was done recently, is a change in optempo (operational tempo) – from very high optempo to very low optempo, or very low optempo to very high optempo – that’s where we see the greatest increase in risk. Units that remain in low optempo, they’re able to look at that low optempo and mitigate risk ahead of time, and same when we’re in high optempo. We’ve discovered it’s the fluctuation between the two is when we see the increased level of risk out there.”