WASHINGTON NAVY YARD – Lt. j.g. Sarah B. Coppock was contrite and quiet when she pleaded guilty on a single criminal charge for her role in the collision between the guided-missile destroyer USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and a merchant ship that killed seven sailors.

Before a military judge and almost a dozen family members of the sailors who died, she pleaded guilty to one violation of Article 92 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

Coppock was the officer of the deck when Fitzgerald collided with ACX Crystal off the coast of Japan on June 17. As part of a plea arrangement, she told military judge Capt. Charles Purnell her actions were partially responsible for the deaths of the sailors who drowned in their berthing after the collision.

“My entire career my guys have been my number one priority,” she said.

“When it mattered, I failed them. I made a tremendously bad decision and they paid the price.”

In her plea, Coppock admitted that she violated ship commander Cmdr. Bryce Benson’s standing orders several times during the overnight transit off the coast of Japan, violated Coast Guard navigation rules, did not communicate effectively with the watch standers in the Combat Information Center, did not operate safely in a high-density traffic condition and did not alert the crew ahead of a collision.

Purnell sentenced her three months reduced pay and issued a punitive reprimand.

While Coppock did admit to wrongdoing, both the prosecutors and defense attorneys painted a picture of a difficult operating environment.

When Fitzgerald collided with Crystal, the malfunctioning SPS-73 bridge radar was tracking more than 200 surface tracks – a mix of large merchant ships and fishing vessels near the coast of Japan, according to the findings of fact in the trial. Coppock was under orders for the ship to cross a busy merchant shipping lane – a so-called traffic separation – that wasn’t labeled on the charts provided by the navigation team. She was also ordered to keep the ship moving at a high-rate of speed during the transit – 20 to 22 knots. The high speed lowered the time the crew could react to ships around them.

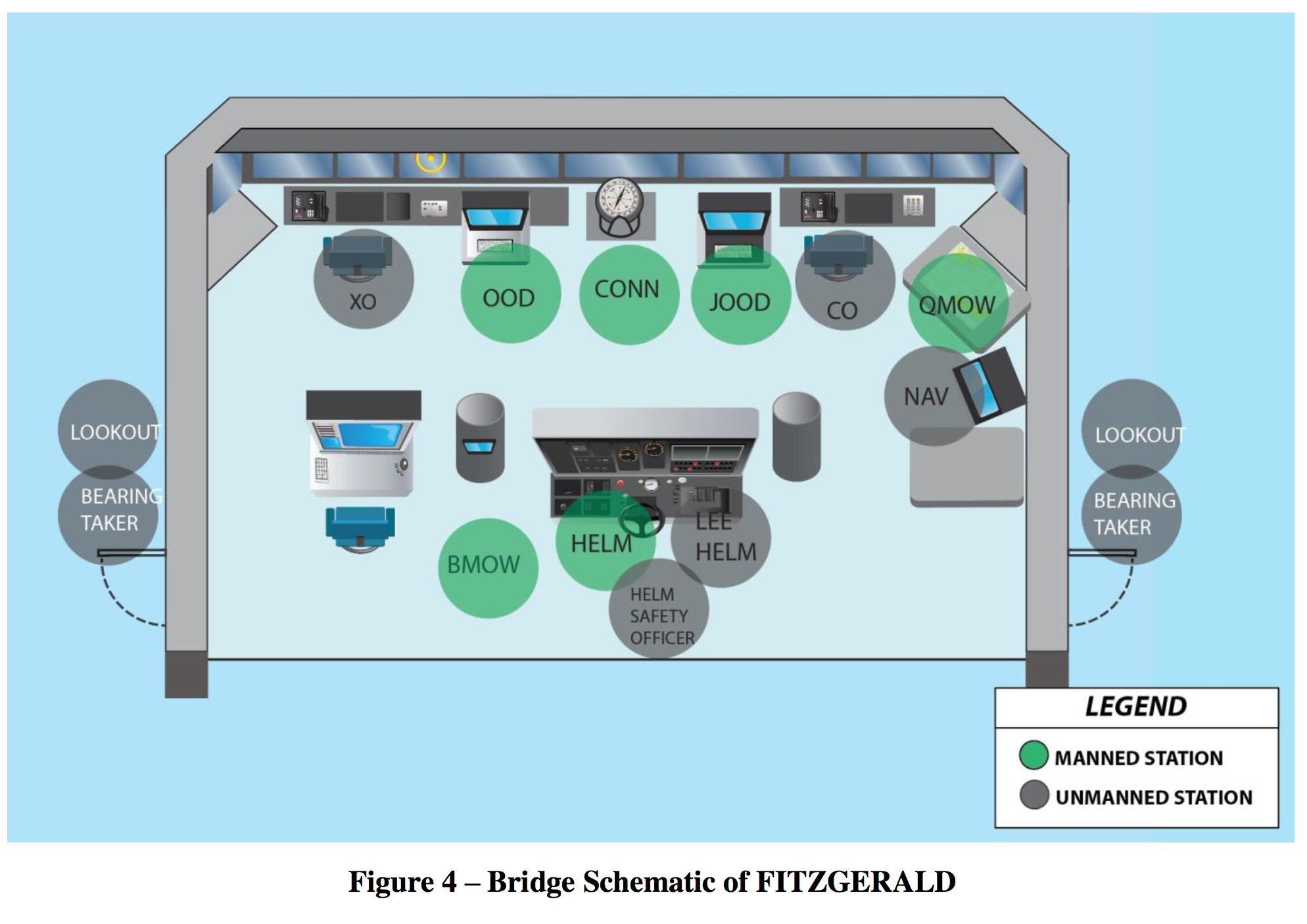

Coppock said she didn’t rely enough on the officers on watch in the ship’s combat information center (CIC) to help keep track of the surface contacts as a back up to her crew on the bridge. Prosecutors and defense attorneys that the conditions aboard Fitzgerald made the collision more likely.

“Coppock failed in her duties, but she received very little support,” prosecutor Lt. Cmdr. Paul Hochmuth argued during the sentencing portion of the trial.

“Being complacent was the standard on USS Fitzgerald.”

During the sentencing portion of the trial, lawyers for the defense outlined the gapped billets and inability to complete training on Fitzgerald. For example, the ship had been without a chief quartermaster for two years before the collision, and the SPS-73 navigation radar was unreliable, defense attorney Lt. Ryan Mooney said, quoting from the Navy’s investigation into the collision. The watch stander in the CIC who operated the SPS-67 search and surveillance radar was unfamiliar with the system.

“Lt. Coppock was not put in a position to succeed,” Mooney said.

“She was set up to fail.”

As part of her statement to the court, Coppock described a tattoo on her left wrist that she got shortly after she returned to shore after the incident. The tattoo includes the coordinates of the location of the collision; the motto of the ship, “Protect your People”; and seven shamrocks, one for each of the sailors who drowned in the flooded berthing.

“I’ll never forget [the coordinates],” she told the judge.

“I spent two hours yelling it in a radio trying to get help.”

The trial now supersedes a non-judicial punishment issuance by then-U.S. 7th Fleet commander Vice Adm. Joseph Aucoin for Coppock shortly following the collision. Her case was reconsidered for court-martial following the assignment of Adm. James Caldwell, director of Naval Reactors, as the Consolidated Disposition Authority who was appointed to oversee additional accountability actions for the Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) collisions.

One military attorney told USNI News that trying a service member at court-martial after assigning punishment at NJP was an unusual move.

“It’s unusual to follow [non-judicial punishment] with a court-martial,” Rob “Butch” Bracknell, a former Marine and military lawyer, told USNI News on Tuesday.

“So the increased punishment is effectively a couple thousand dollars fine and a misdemeanor conviction on a charge of dereliction resulting in death? What was the point?”

The charge Coppock faced on Tuesday as part of the plea agreement was less severe than charges announced by the Navy in January, in which Coppock and two other unidentified junior officers on Fitzgerald faced a combination of charges that included negligent homicide and hazarding a vessel.

While not specified in the trial, the nature of the plea agreement suggests Coppock will likely be a prosecution witness against the upcoming courts-martial of then-Fitzgerald commander Benson or the two other junior officers who have been charged, two military lawyers told USNI News last week.

The two watchstanders who were in the CIC during the collision will face a judge on Wednesday for preliminary hearings on criminal charges for their roles in the collision that include hazarding a vessel and negligence.