NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. – The Navy is emphasizing the development of technologies that can rapidly increase the capability of today’s force, but they are finding this drive for innovation must also come with enough structure to keep high-risk and high-reward programs on track.

Recent examples of innovation at all levels in the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard are not hard to find, with many speakers at the Navy League’s Sea Air Space 2018 symposium this week highlighting innovation within their portfolios. For the Navy in particular, with leadership looking for an exponential increase in fleet capability that comes faster and cheaper than the traditional approach of building more ships and planes, accelerated acquisition and innovative solutions to operational problems are an attractive approach.

Vice Adm. Bill Merz, the Navy’s deputy chief of naval operations for warfare systems, said this week at the symposium that, after funding readiness as a top priority in the past three budget requests, “capability is where we would really like to put most of our energy – that’s where we can turn the capability and make our fleet more lethal much more quickly than just building capacity. And then there’s the capacity piece, the 355-ship navy.”

The Navy is not seeking the fastest-possible approach to reaching its stated 355-ship requirement, but is instead looking to boost the lethality of existing ships through investments in unmanned systems, new weapons like lasers, additional ways to network together ships and sensors, and more.

Merz told USNI News on Monday that he is looking to invest in projects that will boost fleet “capability, which is a slightly higher priority for us than capacity.”

U.S. Marine Corps Lance Cpl. David Bobbie with 3rd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, replaces the battery for an InstanEye quadcopter during a Quads for Squads training event on Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms, Calif., Feb. 28, 2018. US Marine Corps Photo

“We can turn those much more quickly than building a whole new ship and getting it fielded,” he told USNI News after his Monday panel talk.

“If you just add new ships, that’s just a linear improvement to what we’re already doing. If you can build ships and put this kind of capability on it, now you get a geometric improvement or maybe even an exponential improvement.”

To give the innovations some top-cover from Navy leadership – and also to provide some oversight – the Navy and Marine Corps are working through an Accelerated Acquisition Board of Directors that meets quarterly and votes on which projects to take a chance on. Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition James Geurts chairs the board alongside either the chief of naval operations or the commandant of the Marine Corps, depending on whose project the board is considering.

Merz said during the symposium that, thanks to acquisition authorities Congress gave the military services, they can bypass testing requirements and jump to the front of the line for funding in some cases – but not just any program deserves this kind of treatment, he said, and the Navy and Marine Corps are trying to prove judicious in using these authorities.

The Accelerated Acquisition Board of Directors must ask itself, “can we develop this? Can we develop it quickly or accelerate it? And then, should we? Because there’s an opportunity cost every time we do this,” Merz said.

“Sometimes things frankly don’t need to be accelerated,” particularly if a system’s entry to the fleet is properly phased with the sundown of a legacy system, or if the threat it protects against remains consistent.

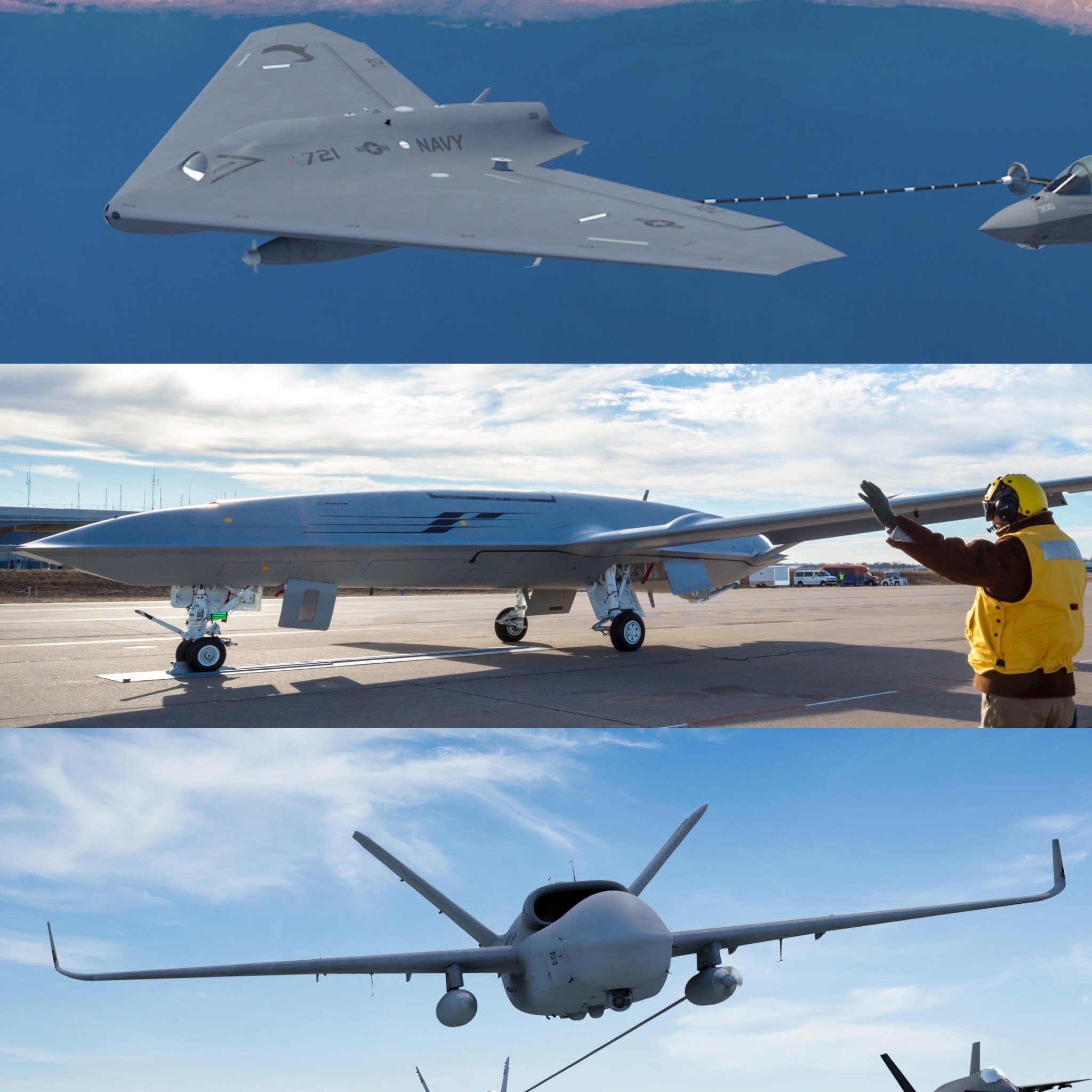

But because the programs that are approved by the AA BoD can be high-cost and high-stakes programs – such as the MQ-25A Stingray unmanned carrier-based tanker and the Large Diameter Unmanned Underwater Vehicle programs – the BoD provides top cover and a “bubble of protection … until you get through a demonstration and show this thing works,” Merz said.

He added that the BoD approval to move ahead also signals a “full commitment” to the program.

Top to Bottom: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Atomics

“If this thing works, are we going to commit to it or not? And if it doesn’t work, alright, no harm no foul. Nobody’s in a hurry to fail, but boy is it better to fail upfront,” he said.

“The whole chain of command understands the high probability of failure, and everybody’s okay with it.”

The mood for innovation is prevalent throughout the sea services. The Coast Guard found itself in the middle of its Hurricane Harvey rescue effort in Texas with an unprecedented amount of data at its disposal regarding where their helicopters and rescue swimmers were needed, but with no program of record to help make sense of that data and create any kind of usable decision-making tool, Vice Adm. Sandra Stosz, the Coast Guard’s deputy commandant for mission support, said in a Tuesday panel.

“We were getting calls, postings on Facebook and other social media, street addresses – here’s my house, I’m in distress. How do you vector a helicopter in that?” she said.

The Coast Guard slapped together some cloud computing and geolocating technologies that created heat maps, which allowed commanders to send rescue teams where they were most needed. Stosz said the process not only allowed the Coast Guard to rescue more than 11,000 people and pets in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, but it also provided an opportunity to test out a new system and get real-time feedback instead of working through a years-long formal acquisition process.

Stosz said the Coast Guard is also trying to use a similar approach in its quest for a small unmanned aerial system to assist in search and rescue missions – while program officers work on creating a formal program of record for the Guppy UAS, some units have already volunteered to take on prototype systems to start figuring out concepts of operations and better refining the list of requirements from the operators’ perspective.

For the Marine Corps, innovation in UAS is leading to innovation in other areas too. Every infantry squad will get a small UAS to “look around a corner, look around a building, look around a hill,” Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. Glenn Walters said in a Monday panel. But the small UAS systems are not the most durable, and rather than create a complex logistics chain to support a simple tool, Walters said the Marines are doubling down on their innovation by pairing the small UAS with additive manufacturing.

“Marine will crash those little quadcopters, but the good news is they go back and just print those little parts, put the motor back in. And they’re doing it, they’re doing it now,” he said.

3D printers are being fielded at the battalion level now, though at least one aviation squadron already invested in its own printer to help print little things like buttons on their aircrafts’ circuit breakers that break regularly and take weeks to order and receive replacement parts.

“The next thing we ought to do is get them a scanner so they can scan the stuff,” Walters said – if the operators used a laser scanner up-front to scan any parts they might need to print, the process would be all the faster if they could just look up the scan in their database and hit print.

“That’s innovation, and that will cut down a lot of downtime for recovering readiness.”

Lt. Gen. Robert Walsh, the deputy commandant of the Marine Corps for combat development and integration, said in a Tuesday panel that the Marine Corps was innovating all throughout the service, but that leadership was keeping the effort on the rails by not going all-in on an idea until it had proven itself in the field.

“The things we’ll procure, we’ll procure in a small amount. We might buy four battalions’ worth and see how that’s going with four battalions’ worth, and then see what the technology’s doing,” he said, when asked how to balance the eagerness to innovate with the need to ensure money isn’t wasted on too many failed projects.

“It could be a small UAS: go buy four battalions’ worth, see how it works, see what the Marines like. If they like it then continue buying more. And if something else comes in that works better, then we change out and go to that vendor. So I think that’s one way: don’t buy the whole thing all at once, but set incremental buys up.”