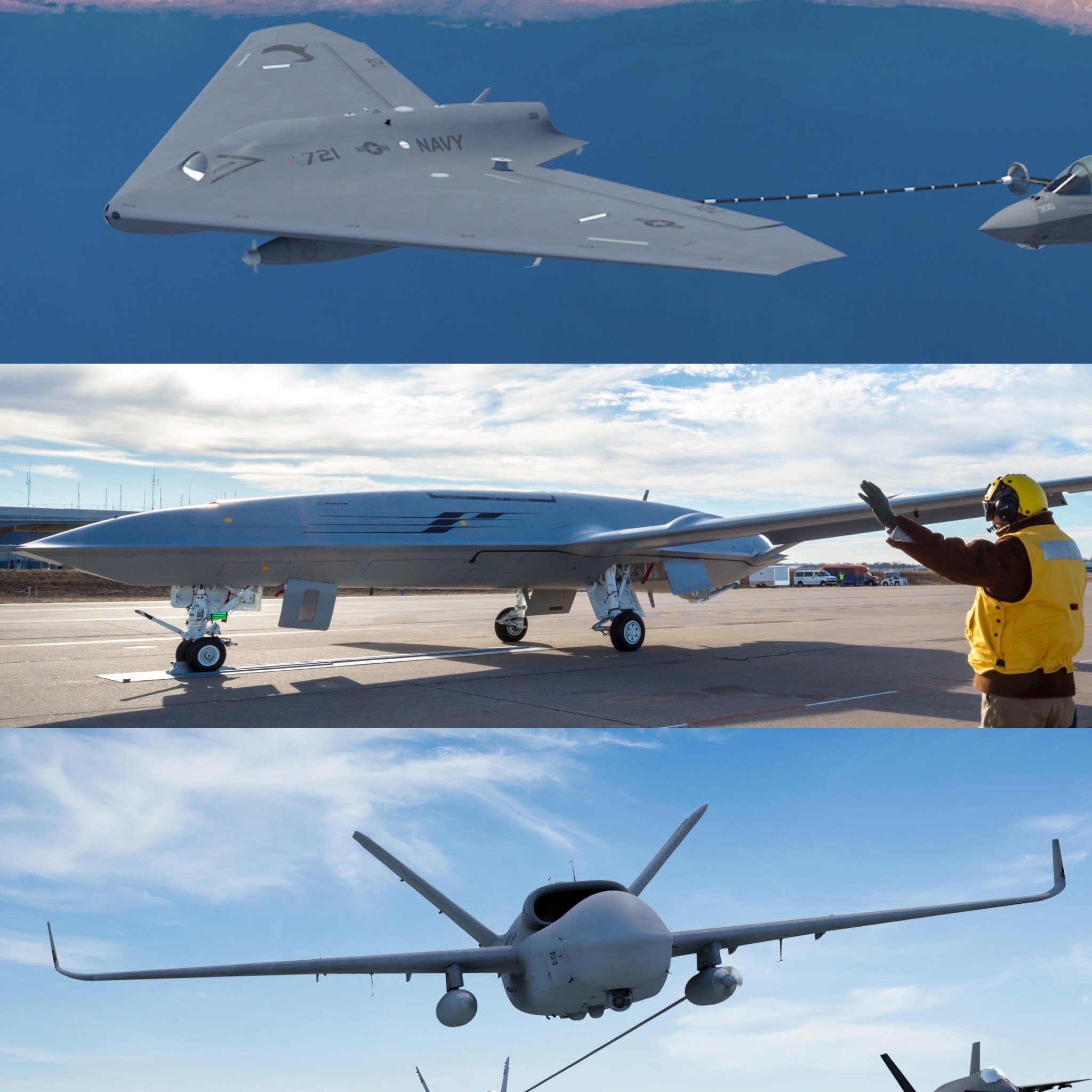

Top to Bottom: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Atomics

ST. LOUIS — After years of requirements churn and program uncertainty, the signal to companies vying to build the Navy’s first operational unmanned carrier aircraft is crystal clear: the Navy wants the MQ-25A Stingray as soon as possible.

On Jan. 3, Boeing, Lockheed Martin and General Atomics all submitted their responses to the Navy’s final request for proposal for the airframe of the Stingray and are expecting the service to select a final design as soon as this summer.

The procurement schedule was accelerated at the behest of Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson, Boeing MQ-25A program manager and former program executive officer for Navy tactical aircraft B.D. Gaddis told reporters on Thursday.

“His number-one priority is the schedule. Price is number two. He wants this airplane out there quickly. The request for proposals and the source selection criteria reflect those priorities really, really well in terms of accelerating the schedule,” Gaddis said.

“He’s putting the pedal to the floor. Normally it takes NAVAIR about 18 months to do a source selection like this. They’re going to do it six months. When the CNO said he wanted to accelerate the schedule, he meant it.”

Outside of the requirements to industry, the service signaled it was bent on moving quickly on the program by including $719 million for the program development and the first four production airframes as part of its Fiscal Year 2019 budget submission.

The program has been moving quickly since the Office of the Secreatary of the Defense watered down the requirements of the Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) concept and pushed companies to focus on the tanking requirement.

The decision to focus on tanking was the result of a strategic review of the UCLASS program led by then-Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work as Congress and the Navy struggled with how to define the role of UCLASS in the fleet.

“Going back to the UCLASS days, there’s a lot of… not everyone was aligned — to say it nicely — between Congress, OSD and the Navy and the fleet on the requirements,” Gaddis said.

A major driver of the program shift was to provide much-needed relief to the fleet’s already overworked F/A-18E/F Super Hornets that are burning up to 20 to 30 percent of their flight hours as tankers for deployed air wings.

The Navy has been vague about the requirements, but USNI News understands the service’s basic requirements will have the Stingray deliver about 15,000 pounds of fuel up to 500 nautical miles from the carrier.

As part of an earlier risk-reduction contract that also included Northrop Grumman, all the competitors were required to conduct a tanking trade study to best configure their offering for the MQ-25A work.

Based on those findings, Boeing and Lockheed Martin both determined modified versions of their UCLASS pitches would fit the bill for the service.

From 2012 to 2014, Boeing’s Phantom Works quietly built a flying prototype of its UCLASS design, built around a Rolls-Royce AE 3007 engine.

As the competition moves forward, Boeing is the only current competitor to have revealed a working prototype for its Stingray bid, since Northrop Grumman dropped its X-47B design out of the competition late last year.

“We had to go through that entire study, just like we did with UCLASS, to make sure that we had the right engine, we had the right design to see if we had to change anything substantial, and the answer that came out of that study was that we no we didn’t,” Gaddis said.

“Now that it’s just a tanker with little [information, surveillance and reconnaissance], we’re still in the wheelhouse with this requirement.”

Likewise, Lockheed Martin based its bid on its original UCLASS design. Lockheed had pushed a flying-wing design for its UCLASS offering that could grow into a stealthier platform more easily, Lockheed Martin’s MQ-25A program manager John Vinson told USNI News last week.

“We spent a lot of time at looking at what I would call conventional winged aircraft, but we also continued to look at our old UCLASS design, which has been designed as a stealthy first-day unfettered-access kind of ISR asset,” Vinson said.

“What can we do with the flying wing if we relax that stealthy, unfettered access requirement?”

In September, representatives from General Atomics said their bid was going to borrow heavily from the company’s experience in developing its MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper remotely piloted aircraft for the Air Force, in addition to the company’s Sea Avenger concept design.

Ahead of the final selection, the competitors will have to prove a deck handling demonstration for their airframes as part of the ongoing risk-reduction contracts.

While the companies are vying for the airframe, the Navy is responsible for designing and developing the data links and the ground control station and acting as the lead systems integrator for the effort. Much of that work was part of the Navy’s X-47B carrier launch and recovery tests in 2013 and 2014.

Moving ahead, the real challenge isn’t launching a UAV on and off the carrier but how the aircraft will fit into the airwing and the strike group.

“What’s the breakthrough that’s going to occur with the MQ-25? It’s not frankly the ability to operate an unmanned air system off a carrier. We know how to do that,” outgoing Skunk Works head Rob Weiss told reporters on Monday.

“The learning opportunity is going to be manned, unmanned teaming.”