CAPITOL HILL — Navy leaders told lawmakers today the Fiscal Year 2019 budget request and long-range shipbuilding plan were both crafted with industrial base health in mind, despite worries from some congressmen and shipbuilders that the plan was full of missed opportunities.

From small surface combatants to attack submarines to aircraft carriers, lawmakers have worried about discrepancies between industrial base capacity and the Navy’s stated acquisition plans, which represent a baseline minimum requirement rather than an aggressive stretch goal.

In a House Armed Services seapower and projection forces subcommittee hearing on Tuesday, Vice Adm. Bill Merz, deputy chief of naval operations for warfare systems (OPNAV N9), said the annual 30-year shipbuilding plan prioritizes industry in a way it never has before, but that “we have to provide a balanced Navy. And with that, we are unlikely to ask for ships above our requirement” as laid out in a 2016 Force Structure Assessment.

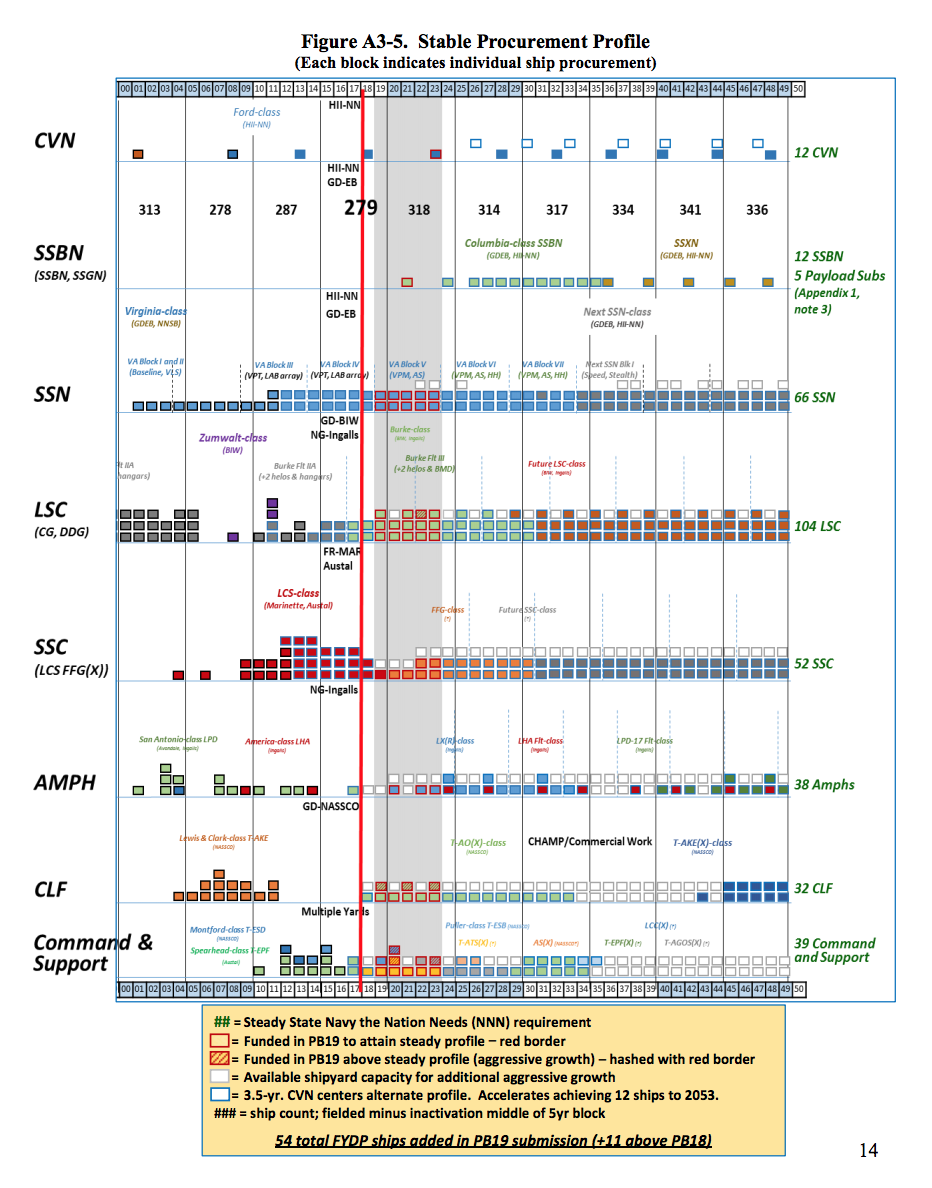

That duality – highlighted in the shipbuilding plan itself, in a graphic showing year-by-year tallies of where industry will have additional capacity that the Navy does not plan to take advantage of – was the focus of much discussion during the hearing.

Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2019

Subcommittee ranking member Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.) said in his opening statement that the 30-year plan “does not achieve the minimum Navy force size the Navy says it needs until the 2050s. Looking closely at the budget and the shipbuilding plan, it is clear that there is still substantial ‘meat on the bone’ where industrial base capacity may exist to add further ships and capabilities to the fleet,” he said.

Merz told Courtney later in the hearing that, despite the many instances of untapped industry capacity – with the aircraft carrier industrial base, with attack submarines, with large and small surface combatants, and so on – “as we take advantage of a steady funding stream over time, one of the key elements is incentivizing industry to invest also along with us so we can grow that unused capacity over time and then obviously take advantage of it so we can get (to 355 ships) faster.”

He did not elaborate on why industry might feel comfortable investing when the Navy’s official plan of record does not take advantage of the yards’ full capacity but rather cedes that initiative to Congress, who could fill in gaps if lawmakers chose to fund Navy shipbuilding beyond the requirements-only request.

“We know it’s an unsatisfying ramp (to 355 ships),” Merz told Courtney, but for the sake of maintaining balance in the Navy’s readiness, personnel and other spending accounts, “we felt we hit the mark on what we have to do to set a base profile that we cannot go below or we will not grow at all, and we have to protect that, and then take advantage of any aggressive road that we might be able to support with Congress’s help going forward.”

Small Surface Combatants

A near-term example of the Navy funding to their hull-specific requirement rather than to industrial base needs is with the Littoral Combat Ship. Both LCS builders, Austal USA and Lockheed Martin/Fincantieri Marinette Marine optimized their yards to build two ships a year each, and the Navy said as recently as last year that it needed to buy at least three ships a year total – one and a half per yard – to keep the two yards healthy enough to compete for the upcoming frigate program, which will follow LCS acquisition for the small surface combatant portion of the fleet.

Still, because the Navy only has a requirement for 32 LCSs, the Navy only requested just one ship in FY 2019 – though due to lawmakers adding an additional LCS into the 2018 spending plan, which still awaits final passage from Congress, the FY 2019 ship would actually be the 33rd in the program.

Both shipyards told USNI News that one ship in 2019 was not sufficient to sustain them, as they both plan to compete for the frigate contract and need to keep their LCS production lines hot to remain viable candidates for that future frigate work.

“The one requested ship for FY ‘19 will lead to a gap in production that would negatively impact the yards, which will result in job losses at the yards and increased cost for the Navy,” Rep. Bradley Byrne (R-Ala.), whose district includes the Austal USA shipyard in Mobile, said during the hearing.

“The problem here is that we were supposed to transition to the frigate this year; the Navy wasn’t ready, so the present plan is to transition next year. So we’ve got two shipyards affected here. … You, the Navy, and Congress, we’ve got to figure out together if we can work it so that these shipyards don’t crumble on us. Because without that, you will not have an effective competition for the frigate.”

Despite that concerns, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition James Geurts said that, with three ships in 2018 and one in 2019, “you’ll have four ships over the next two years – certainly not at the optimal level, I believe it’s at the minimum sustaining level so we will not completely lose the workforce or the work yard, but I do acknowledge that would probably cause some work turndown in those yards as we go back into frigate and execute that downselect.”

Byrne shot back that a skilled workforce is not something that can be cut and then built back up with any ease, and he pointedly asked, “is the Navy willing to accept the risk that these two yards would be effectively crippled before that frigate contract is awarded?”

“I don’t believe that will threaten the competition itself, but obviously not operating at optimal production rates will cause some concern for workers, and that workforce will have to spin back up as we make this transition,” Geurts replied.

Byrne implored the Navy to work with Congress to find a smarter way to transition from LCS to the next-generation frigate (FFG(X)), adding “one ship’s not going to do it, I think that’s pretty clear.”

Regarding workforce levels, if either Austal or Marinette were to ramp down for the 2019 LCS plan and then win the frigate competition, “it’s not spin back up, it’s long periods of time to get large numbers of people back to a program, get the level of experience back up to the optimal level – it will take years,” Byrne said.

“And whereas some large shipyards might be able to survive that, these two shipyards are small shipyards – the one in Marinette and the one in Mobile – they may not. And in fact, I think the likelihood is at least one of them won’t survive” the frigate transition at all.

Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wisc.), whose district includes the Marinette Marine yard, said at the hearing, “I think we all want the same thing: we want, as you laid out, to preserve the industrial base, we want to make sure we have as robust a competition for the frigate as humanly possible, learning lessons from the past mistakes that we’ve made, and also get to 355 in as expeditious but also as sustainable a manner as possible.”

Geurts told USNI News after the hearing that the Navy chose to buy the 33rd LCS in 2019 “knowing that’s a little bit above our requirement but that it was absolutely critical, making sure we had both those yards in a position where they could compete fairly for the frigate. We believe we’re in that position.”

Asked if the Navy could assure Austal or Lockheed Martin/Marinette Marine that they wouldn’t be disadvantaged in the frigate competition if LCS cost and schedule were hurt by 2019 LCS decisions, he said, “I believe we’re going to set up the competition so it’s fair and equitable.” Five builders are currently on contract for ship design maturation work, which Geurts said would inform the frigate requirements and selection criteria in the request for proposals next summer, and “if there’s issues when they see the criteria, obviously that’s what we’ll work before we release our final RFP.”

Aircraft Carriers

The aircraft carrier portion of the Navy’s 30-year plan continues the current five-year centers for buying the ships, eventually moving to four-year centers. The industrial base has said in recent years it would like to see three-and-a-half year centers for optimal efficiency.

Merz said in the hearing that the Navy was still looking for more aggressive ways to reach their goal of 12 aircraft carriers – the last ship type that will hit its requirement under the 30-year plan.

Even three-and-a-half-year centers “is probably not aggressive enough. Right now on the four-year centers we achieve 12 in the 2060 timeframe; if we go to three and a half that still only moves it up to the early 2050s. So we’re aggressively looking at that,” he said.

In the near term, Geurts said the Navy is working with industry to understand how to make the production line more efficient, with a careful eye on the potential for block-buy savings if the Navy bought material for CVN-80 and 81 together.

Geurts told the subcommittee that previous two-carrier buys in the Nimitz-class achieved about 10-percent savings, though the service is already halfway through buying material for CVN-80 so it remains unclear how much potential is left with this particular opportunity.

Pressed to provide some sort of cost-savings estimate, Geurts said, “it depends on when we implement it. I would say somewhere between, certainly over a billion dollars, up to two and a half billion. And then if you were to do a follow-on carrier buy and you were able to take costs out of the carriers as we expect, you would get follow-on savings to those future carriers.”

Attack Submarines

Courtney, whose district includes the General Dynamics Electric Boat yard that builds submarines, said in his opening statement that, among the missed opportunities to take advantage of industrial base capacity to help reach 355 ships faster, “one glaring example of this opportunity is in the undersea fleet. While the budget reflects a sustained two-a-year construction rate for Virginia-class submarines, at this rate the force would not achieve the 66-boat [requirement] until 2048 – 30 years from now. The 30-year shipbuilding plan identifies specific opportunities in 2022 and 2023 where there is industrial base capacity for a third submarine in each of those years, within the next five-year block contract being negotiated between the Navy and industry.”

The Navy made a massive request for 2019 spending on the Virginia-class program, but much of the funding was to help kick off the new block contract. The request buys two SSNs for $4.373 billion, as well as allots $1.8 billion for advance procurement and $985 million for economic order quantity spending to help achieve cost savings throughout the entirety of this new block contract, the Navy told USNI News. The Navy could not discuss per-hull cost estimates for the Block V contract, which will introduce the Virginia Payload Module to the SSN design, due to ongoing contract negotiations with the submarine builders. However, the service said the $4.373 billion figure represents “an educated cost assessment based on the [Virginia-class submarine] Block IV costs currently, and all estimates provided by the shipbuilders to add the [Virginia Payload Module] section into the boat. The actual cost will be close to the estimated cost, however contract negotiations are required to firmly define the cost of both FY19-1 and FY19-2 hulls,” according to a statement provided to USNI News.

The Navy originally planned for the Block V contract to cover 10 ships, like the five-year 10-boat Block IV contract, but lawmakers put into the FY 2018 National Defense Authorization Act that the contract allows the purchase of up to 13 boats.

Courtney said during the hearing that “Congress has already demonstrated it strong support for expanding the attack submarine production line. Specifically, we provided the authority needed to go beyond two submarines a year in the next five-year block contract. I urge the Navy to take advantage of this opportunity and others like it that provide finite opportunity in the years ahead to add to the plan presented to us here today.”