THE PENTAGON – The Navy historically doesn’t learn from its mistakes, needs better command and control structures to operate the fleet, and needs to be more honest with Congress and the White House about the capabilities it can provide the nation, were key findings contained in a strategic review of the service released on Thursday.

The Strategic Readiness Review is a wide look at the systemic failures throughout the service that led to the deaths of 17 sailors in the Western Pacific in two fatal ship collisions this year. The report found an underlying pattern of problems that have plagued the service since the end of the Cold War in 1989.

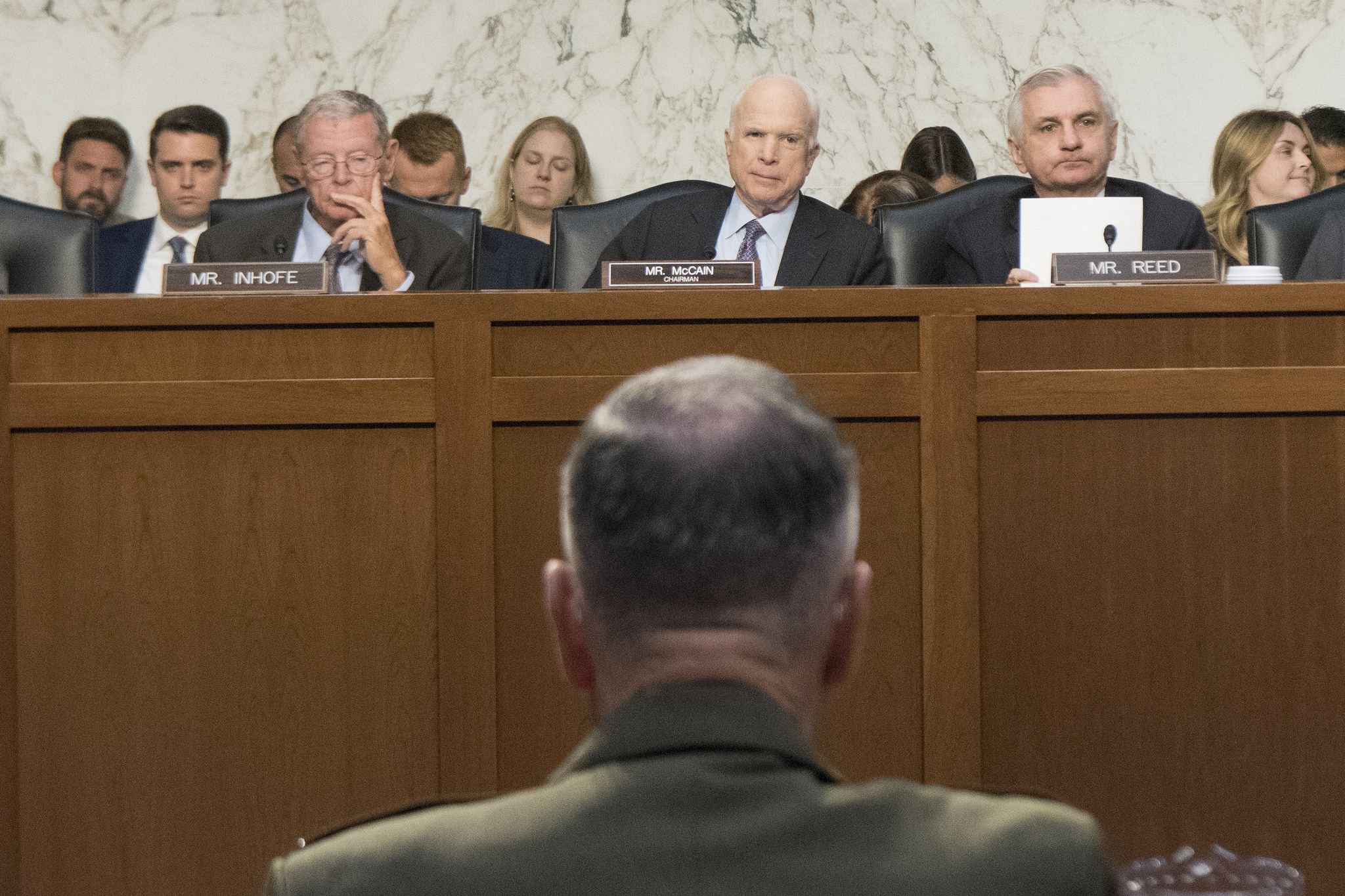

The review, conducted by former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Gary Roughead and Defense Business Board Chairman Michael Bayer at the request of Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spencer, found the Navy had slowly lost its ability to sustain a pace of operations over decades through top-down decisions that have had unintended consequences.

“The cumulative effects of well-meaning decisions designed to achieve short-term operational effectiveness and efficiencies have often produced unintended negative consequences which, in turn, degraded necessary long-term operational capability,” read the report.

“Simultaneously, Navy leaders accumulated greater and greater risk in order to accomplish the missions at hand, which unintentionally altered the Navy’s culture and, at levels above the Navy, distorted perceptions of the readiness of the fleet.”

The report outlines in detail how long-term training, readiness and maintenance needs were traded for short-term operational gain, which led to a condition Bayer and Roughead call “normalization of deviation.”

“With fewer resources available, ship crew workloads grew significantly, expanding their work days and weeks to unsustainable levels. Fleet level processes and procedures designed for safe and effective operations were increasingly relaxed due to time and fiscal constraints, and the ‘normalization-of-deviation’ began to take root in the culture of the fleet,” wrote Bayer and Roughead.

“Leaders and organizations began to lose sight of what ‘right’ looked like, and to accept these altered conditions and reduced readiness standards as the new normal.”

The pair said the degradation in readiness was accelerated, in part, by how the Navy interpreted tenets of the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Defense Act that created more overhead controls on the military and moved the warfighting decisions from the Navy to the global network of combatant commanders.

“Well-intended implementation decisions by the Navy did not adequately preserve and prioritize critical service operational skills, development and training,” the pair wrote.

“Staffs became distracted and inattentive to readiness and did not apply preventative measures to anticipate or address the increasing operational risk.”

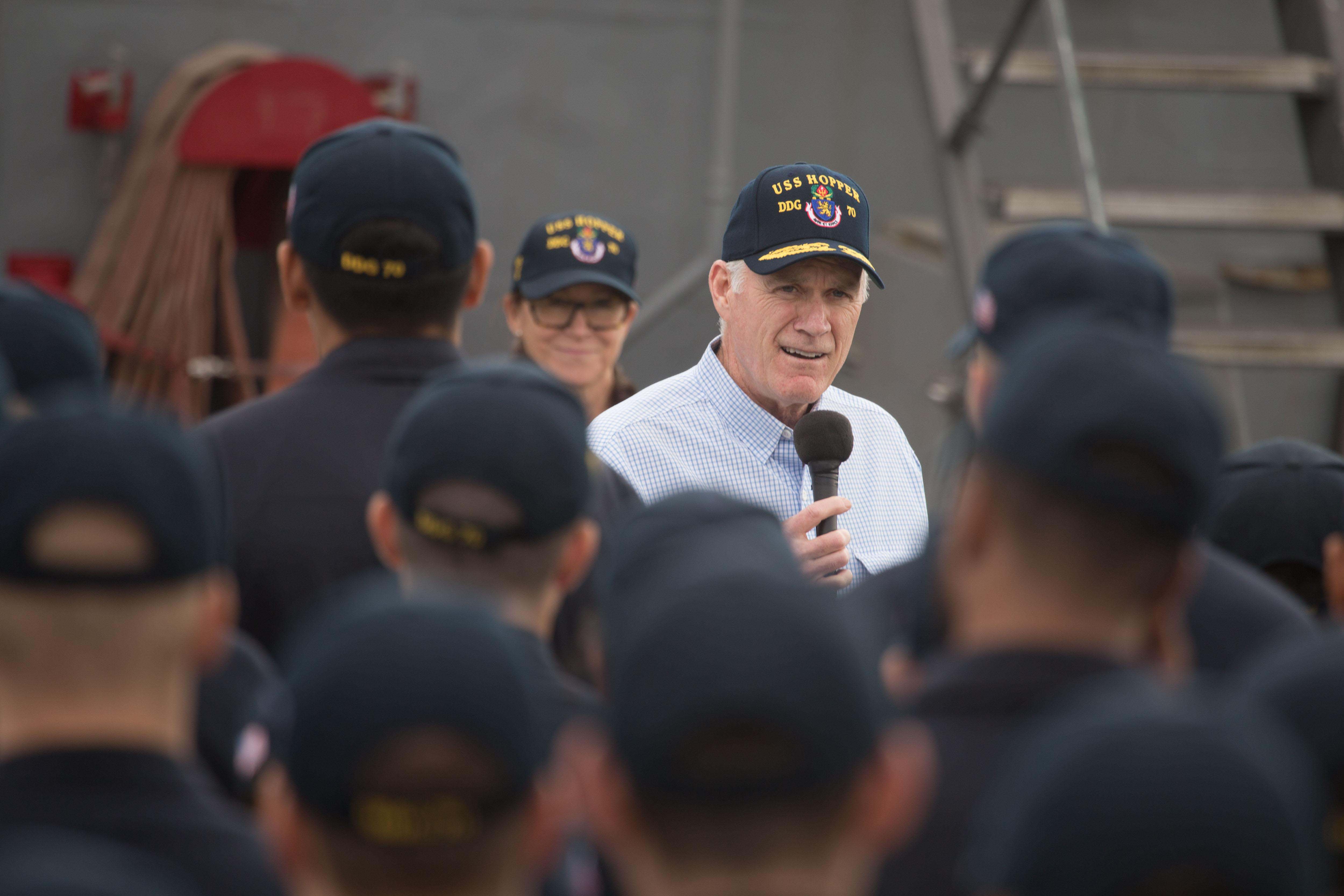

Acting on the report’s recommendations, Spencer is now set to adjust the course for the service that faces more of a threat from near-peer competitors than it has since the collapse of Cold War.

“We have our near-peers out there now, and this is clearly driving this study,” Spencer told reporters this week without specifically naming Russia or China.

“We try and hit this as hard as we can by saying, due to the fact that we have this near-peer reemergence, we have to think about the way we’re applying assets because we’ve been fighting smaller regionalized [threats].”

For example, in its recommendations, the review calls for reestablishing the U.S. 2nd Fleet with an eye toward near-peer competition in the Atlantic and shutter the Navy’s 4th Fleet that patrols South America and the Carribean.

The effort from Spencer comes as the Pentagon as a whole is rethinking how it will fight its wars in the future as it develops its wider national defense strategy that will inform the Fiscal Year 2019 budget.

Spencer’s strategic review follows a more tactically focused comprehensive review into the surface forces in the Western Pacific that was directed by Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson and conducted by U.S. Fleet Forces after the fatal collisions of USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and USS John McCain (DDG-56).

Supply versus Demand

Spencer told USNI News when he first launched his strategic review effort that he wanted the review to question the two-fleet construct of the Navy, the division of combatant commands and the request process that allows combatant commanders to request double the amount of missions that naval forces can actually provide.

Spencer spoke extensively to reporters on that last point, noting the importance of adhering to a supply-based force management system rather than one driven by regional combatant commander demands.

The Navy and Marine Corps need to make clear what assets they have that are ready to be deployed as part of the joint service Global Force Management process, and not allow combatant commanders to take more forces for short-term gain at the risk of long-term readiness, he said.

“We really have to have a clear communication with Congress and with the American public as to what we can do and what we can’t do. I don’t think that communication has been clear – not intentionally,” he said at the press roundtable.

“I think you’ve heard me say this before, this is an organization that’s biased for action, which you want in your military. It’s also an organization that can’t find the word ‘no’ that easily – that’s what you want, but it has to be balanced with sustainability, and that’s what we lost was the sustainability in the equation.”

The Fleet Forces-led comprehensive review earlier this fall noted the detrimental effects of the Navy running ragged to meet COCOM demands in the Pacific.

Spencer made clear at the roundtable that if the Navy felt it only had X-number of ready assets for COCOMs to task, the service should not allow itself to be forced to provide “X-plus-3, or 2X,” and that the chief of naval operations, as a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, would be a primary enforcer of this supply-based model.

“I don’t view it as saying what’s less [that the Navy can do for the joint force], I tell them it’s viewing what we can do. And it’s sending a signal to say, if you want us to do more, we do need more,” Spencer said.

“We have to understand exactly what those effects are if we’re going to apply those resources. And that’s the conditioning I’m talking about, where before we’d turn around and say, yup, we can do this, and no one knew – well, very few people understood the havoc it was wreaking in the organization because we weren’t signaling that to the White House and the Hill.”

Though these force allocation issues do not fall under the secretary of the Navy’s portfolio, Spencer said he needed CNO Richardson to advocate them to the Joint Chiefs.

“It takes leadership. If in fact we don’t have the assets, we do not have the assets. If in fact national security is threatened, get us the asset,” he said.

“With the CNO as one of the [chiefs], he has the ability to go, here’s what we can do, guys, here’s what we can’t do. My question is, I want to make sure that that’s institutionalized instead of ad hoc. … If we can have clear inputs into the ready force model, it might be the perfect model. My question is, I don’t think we have clear inputs into that.”

In the event that that doesn’t work, the strategic review suggests that the Navy, “withhold a greater number of ready forces from the force allocation process to be used to respond to emergent requirements.”

Spencer did not comment specifically on what that potential course of action would look like.

He did say, “one of the things we want to see on the administrative side is more direct control by the secretary of the Navy and the chief of naval operations when it comes to asset ownership and asset control. I realize that our job is to man, train, equip, supply and then we have our joint chiefs and the secretary of defense applying those assets, but to have a clearer command line as to how those assets are kept current” and ready.

Reemphasizing Readiness

The strategic review also notes the importance of reestablishing readiness as a priority.

Spencer’s overarching message on readiness was that the surface navy needed the same protections in place as the aviation and submarine communities to ensure readiness remains paramount regardless of global demand for forces.

“On the water has been around for centuries and centuries. Underwater is fairly new and so is in the air, and they come with regulatory constructs, so the communities have a pretty good check and balance system,” he said.

“We want to structure the same and offer the same to the surface warfare community, and it focuses on mastering of naval skills.”

That includes requiring surface warriors to keep logbooks noting their watchstanding experience.

One facet of the readiness rebuilding effort the review highlighted was creating an environment where sailors can truly master their naval skills.

“Automation and technological advances can reduce the number of sailors required to operate a ship but they do not reduce the need for deep naval mastery, in fact, quite the opposite. Smaller crew sizes increase the need for officers who are incentivized to invest in careers at sea,” the report reads.

“Over time, however, Navy choices in response to the combined effects of the Defense Officer Personnel Management Act, the Goldwater-Nichols Act, and Department of Defense guidance shifted the focus of officers’ careers toward more joint and broader experience at the expense of honing deep maritime operating skills.”

The review makes several recommendations aimed at allowing surface warfare officers to become masters of their trade with less distraction, such as requesting amendments to Goldwater Nichols that would require fewer joint force assignments, eliminating the fleet-up model and placing a shore tour between the executive officer and commanding officer assignments, and reviewing the number of department heads needed on a ship and the length of the department head tour.

The report recommends several changes to training and maintenance as well, including altering when operations and maintenance dollars expire, in light of the reality that most fiscal years are likely to start with a continuing resolution instead of an actual spending bill; adopting a Training and Readiness matrix similar to one that exists in the aviation community “to define what each ship must accomplish in each phase of training, the number of times it has to be demonstrated, how many times it can be simulated, and what the external grading criteria are for meeting the requirements for each level of certification;” and reverting back to longer maintenance availabilities instead of today’s model of continuous maintenance “to deal more efficiently with the impacts of emergent work and work delays.”

Command and Control

Bayer and Roughead also issued a call to improve how the Navy commands and controls its forces by increasing oversight in some areas and reducing layers of command in others.

“One of the things we want to see on the administrative side is more direct control by the Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations when it comes to asset ownership and asset control,” Spencer said.

In particular, the pair found that dual-hatted positions in the Pacific and Atlantic were responsible for both maintaining and employing surface forces that created ambiguous chains of commands that constantly needed to be clarified to subordinates.

“The accumulation of these changes to organizational structures, command relationships, and multiple attempts to clarify command authorities suggests that a clean-sheet review is needed to identify the optimal administrative organization,” the report reads.

While Spencer said some recommendations in the report could warrant more in-depth study before implementation, he was clear that he was moving ahead with the clean-sheet study to that would take a top-to-bottom look at how the Navy is organized to manage its forces.

“We’re truly going to clean-sheet review the administrative side of the Navy and how we actually employ forces,” Spencer said.

Learning Organization

In order to process and learn from its mistakes, the Navy needs to become an organization that does a better job learning, the report concluded.

Bayer and Roughead cited a list of reports in their study that repeated the same themes and lessons on which the Navy did not act.

“Navy history is replete with reports and investigations that contain like findings regarding past collisions, groundings, and other operational incidents,” the report reads.

“The repeated recommendations and calls for change belie the belief that the Navy always learns from its mistakes. Navy leadership at all levels must foster a culture of learning and create the structures and processes that fully embrace this commitment.”